Kinetic Theory

After a long foray into sophisticated field theories, we're going to jump into a ball-pit and play with transport. Note that this final topic has very little (pedagogically) to do with all the stuff we've been talking about all quarter. So for better or for worse, the topic of transport will stand as its own independent module.

I would have much preferred to learn about simple close-to-equilibrium dynamics, such as diffusion, the Langevin equation, and fluctuation-dissipation. I think it would provide a nice philosophical wrap-up to the class, since it convincingly explains how an equilibrium ‘‘ensemble’’ results from the dynamics of coupling to an external heat bath.

Since Prof. Kivelson is gone for the American Physical Society's March Meeting this week, we have another guest instructor, the wonderful Prof. Ben Feldman. He took a much more ‘‘traditional’’ active learning approach with well-designed (!) worksheets that guided us through problems.

Motivation: Thinking about Dynamics

Throughout the quarter so far (and honestly through most of the previous quarter!), we've worked with the abstract notion of a ‘‘statistical ensemble’’ over the individual microstates with of a large system. For some reason, we had to believe that ensembles accurately represented the thermodynamic equilibrium state. But we never really went back and explored the arguments and assumptions in detail. What does it really mean to take the average over a huge probability distribution over microstates?

Ultimately, any discussion about thermodynamic equilibrium must come down to a discussion about dynamics – about how microstates change in time, and about how this time evolution ultimately causes the system to end up in special thermal-equilibrium-state where macroscopic observables stop changing. To understand the lack of change, we need to understand the process of change.

Prof. Kivelson has told us repeatedly that the classical theory of thermodynamics has no information about dynamics. So to learn about how macroscopic quantities change in time, we need to step beyond our typical heat engines and free energies. I find it quite exciting – we're finally going to breathe some life into the theory, and allow quantities to change and evolve and morph over time.

The Kinetic Theory

Let me open with a cool gif I made last year in Physics 113. (Ignore the right hand panel for now!)

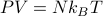

On the left hand panel, I've drawn a toy model for a gas. Microscopically, we can see that a gas looks like a bunch of particles whizzing around and bumping into each other. But macroscopically, we know that a gas behaves quite differently – it obeys the ideal gas law  , it's compressible, it's homogenous, etc.

, it's compressible, it's homogenous, etc.

To explain our day-to-day experience with gases, we turn to the kinetic theory of gases. This theory is a silly caricature that uses bouncing balls to explain all the properties that we know and love. It relies on some simple notions of statistics to describe the huge number of particles, and it relies on a few cartoon arguments, but apart from that, it's a simple and rather enlightening theory.

Keep in mind that we can't take the cartoon picture of bouncing balls too seriously! Of course reality is much more complicated: gases have a rich internal structure of electrons bound to nuclei; the molecules feel an interaction energy with each other; the collisions cause vibrational energy transfer between molecules, and far more. But the point of kinetic theory isn't the details; the purpose is to figure out simple properties from the simplest assumptions.

We're going to be half-assing a lot, because kinetic theory is a ridiculous caricature of reality anyways. So at best we'll probably get results to within an order of magnitude. But that's okay, since the whole purpose of the theory is just to build some simple arguments about the behavior of gases. Don't take factors of 2 too seriously!

Collisions

We begin by considering the question of collisions between the particles of an ideal gas.

In absolutely non-interacting world, the particles would fly right through each other, but such a model would be way too boring. If a particle started off with some speed, then no matter how long you wait, it always has the same speed. Furthermore, the particles wouldn't actually reach thermal equilibrium with each other because they don't exchange energy.

So we make the next simplest assumption: the particles collide with each other so that they can exchange energy. To make our lives easier, we can pretend that the collisions have no other significant effects: they don't add extra terms to the energies, they don't take too long to occur, and so on.

Of course, in reality, the collisions do cause other effects, so what I really mean here is that the ‘‘non-ideal deviations’’ had better be small and unimportant. To be more precise:

The particles had better spend most of their time whizzing through free space rather than colliding with each other. This is a statement about timescales. As the particles fly through free space, it'll take some characteristic time

before it happens to smack into another particle. During the act of collision itself, the electron clouds of the two molecules undergo some nasty smear of Pauli exclusion, which happens very quickly, on the timescale of

before it happens to smack into another particle. During the act of collision itself, the electron clouds of the two molecules undergo some nasty smear of Pauli exclusion, which happens very quickly, on the timescale of  . So we assume that

. So we assume that  .

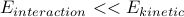

.We also assume that the interaction energy between the molecules is insignificant compared to their kinetic energy,

.

.For good measure, let's also pretend that the size of the particles is puny compared to the distance that they have to travel before they hit another particle. If

is the diameter of a particle, and

is the diameter of a particle, and  is the mean free path, we pretend that

is the mean free path, we pretend that  .

.

And so on and so forth, you get the idea. When we ignore certain aspects of molecular behavior, we're really just saying that its characterisitc lengthscale (timescale) is far shorter than something else we care about.

The rest of this page will be brief.

Collision rates

Say that a particle collides with a rate of

collisions per second. That is, in a time interval of

collisions per second. That is, in a time interval of  , we expect to have

, we expect to have  collisions.

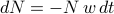

collisions.The number of particles that remain unharmed thus decreases by

during every time interval

during every time interval  . Solving the differential equation, we find that the the number of unharmed particles decays exponentially in time as

. Solving the differential equation, we find that the the number of unharmed particles decays exponentially in time as  .

.The characteristic timescale of this exponential decay tells you roughly how long a particle travels for until it collides with another particle.

We call

the relaxation time.

the relaxation time.We could have found this answer via dimensional analysis: since the collision rate

has units of ‘‘per time’’, the only possibility for something with units of time is

has units of ‘‘per time’’, the only possibility for something with units of time is  .

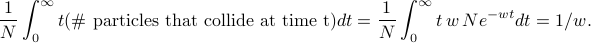

.To fix the constant of proportionality, we have to be a bit more careful with our argument. We see that the number of (unharmed) particles that experience a collision between

and

and  is given by

is given by  =

=  . And thus the average ‘time of collision’ is given by

. And thus the average ‘time of collision’ is given by

Mean Free Paths

The mean free path

is the typical length that a particle travels for before it hits another particle.

is the typical length that a particle travels for before it hits another particle.If

then the particles spends most of their time propogating through free space, so the ideal gas approximation is a good one.

then the particles spends most of their time propogating through free space, so the ideal gas approximation is a good one.

If a particle travels with a typical speed of

, then we see that the mean free path is given by

, then we see that the mean free path is given by  . Nothing too surprising.

. Nothing too surprising.

We can find the mean free path (up to constant factors) via simple dimensional arguments.

First we have to remember that scattering theory tells us that the cross-section

of a scatterer tells you how well it scatters off oncoming particles. The cross-section has units of area and it essentially tells you the effective cross-sectional area when you look at it head-on.

of a scatterer tells you how well it scatters off oncoming particles. The cross-section has units of area and it essentially tells you the effective cross-sectional area when you look at it head-on.For instance, for hard-sphere classical particles (e.g. billiard balls), the cross-sectional area is given by

, where

, where  is the diameter of the sphere. (Yes, that's right; two billiard balls will hit each other if their centers are within a diameter of each other!)

is the diameter of the sphere. (Yes, that's right; two billiard balls will hit each other if their centers are within a diameter of each other!)

So in total, there are two unit-ful parameters that can enter into the mean free path:

the density of the gas (number of particles per unit volume) has units of ‘‘per volume’’:

![[n] = 1 / L^3](eqs/6622479897142866377-130.png) .

.the cross-section of the particles has units of area:

![[sigma_0] = L^2](eqs/2370757368929848611-130.png) .

.

And hence the only reasonable possibility is that

.

.We see that the mean free path is longer for more dilute gases (which makes sense, because there's less particles to collide with), and that it's also longer for particles with a smaller collisional cross-section (which also makes sense because it's harder to collide.)