Solving the 1D Ising Model

Today (Wed Week 2) we went through the solution to the 1D Ising model in detail.

Outline of this lecture

Big picture

What are we trying to do?

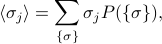

Our end goal is to find various thermodynamic properties of the 1D Ising model. Remember that thermodynamics means that

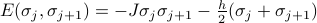

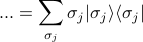

the system is in thermal equilibrum; where the probability of each configuration/microstate is

. (This also called the ‘‘canonical ensemble’’)

. (This also called the ‘‘canonical ensemble’’)we take the

limit – the system is big,

limit – the system is big,

and we're trying to find various properties of these thermodynamic systems.

What sorts of properties?

we're interested in expectation values such as

which tell you the average value of the

which tell you the average value of the  'th spin when the system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium.

'th spin when the system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium.For instance, you can imagine that if there's a very strong magnetic field that wants to align the spins to face downwards, then

will be close to -1. Or that if you heat everything up to very hot, then all the spins are scrambled to be randomly up or down, so

will be close to -1. Or that if you heat everything up to very hot, then all the spins are scrambled to be randomly up or down, so  will be close to 0.

will be close to 0.For the 1D Ising model,

is the same for all values of

is the same for all values of  . Since the Hamiltonian is translationally invariant (see explanation of symmetry), all the sites are identical, and the average spin will be the same no matter which site you look at.

. Since the Hamiltonian is translationally invariant (see explanation of symmetry), all the sites are identical, and the average spin will be the same no matter which site you look at.(Maybe for more complicated or realistic models, the sites would be distinct – as in a heterogenous material – and then perhaps

in general)

in general)

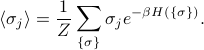

we're also interested in correlation functions such as

, which tell you how much spin

, which tell you how much spin  and spin

and spin  tend to point in the same direction or in opposite directions at equilibrium.

tend to point in the same direction or in opposite directions at equilibrium.For instance, you can imagine that nearby spins are more correlated than faraway spins, because they can interact with eachother more strongly. Or you can imagine that as

, any pairs of spins will become less correlated, since the thermal excitations make all the spins jiggle around more.

, any pairs of spins will become less correlated, since the thermal excitations make all the spins jiggle around more.Again, because of translational invariance (see here for explanation), we expect

to only depend on the distance between the spins

to only depend on the distance between the spins  . For instance, the correlation between spins 2 and 5 is the same as between 100 and 103, since in both cases, the pairs of sites are separated by three lattice spacings.

. For instance, the correlation between spins 2 and 5 is the same as between 100 and 103, since in both cases, the pairs of sites are separated by three lattice spacings.

How do we calculate properties?

Prof. Kivelson outlined the procedure for us on Monday.

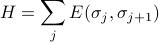

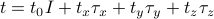

Our system is defined by a Hamiltonian

, a function that tells us its energy.

, a function that tells us its energy.From the Hamiltonian, we figure out the energy eigenstates, a.k.a. configurations, a.k.a. microstates (or sometimes even ‘‘states’’) of the system. These are the basic states, and we will be summing over these states pretty soon.

Yes, these concepts are the same thing! They're just called different words because we learn them in different contexts…

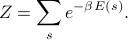

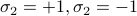

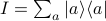

Our main goal is to calculate the partition function

.

.

Here the sum runs over all the states of the system  ,

,  means ‘‘the energy of the system when it's in state s’’, and

means ‘‘the energy of the system when it's in state s’’, and  is the inverse temperature of our system.

is the inverse temperature of our system.

We spend most of our effort trying to figure out how to compute the partition function, which begs the question…

Why is the partition function useful?

Once we've found the partition function  , we can calculate pretty much everything else. For instance:

, we can calculate pretty much everything else. For instance:

the free energy

is given by

is given by

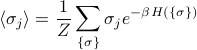

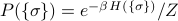

the thermal average spin

is given by

is given by

To explain the notation: I'm summing over all states (this time I call the states  rather than

rather than  ). Inside the sum I am multiplying the spin of the

). Inside the sum I am multiplying the spin of the  'th site (which is

'th site (which is  ) by the Boltzmann weight

) by the Boltzmann weight  . The number

. The number  is the energy of the system when it's in the state

is the energy of the system when it's in the state  , and we find this by plugging in each of the spins

, and we find this by plugging in each of the spins  into the Hamiltonian.

into the Hamiltonian.

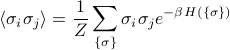

the spin-spin correlation

, which tells you whether spins

, which tells you whether spins  and

and  tend to align at equilibrium, is given by

tend to align at equilibrium, is given by

Hopefully, this serves as a sort of useful roadmap for where we're going.

Solving the 1D Ising Model

Rewrite the Hamiltonian as a sum over bonds (rather than sites AND bonds)

Zoom in on a particular bond and write down a transfer matrix which represents the bond from site

to site

to site  .

.Key step – Notice that summing over

looks an awful lot like contracting over a shared index, a.k.a. matrix multiplication.

looks an awful lot like contracting over a shared index, a.k.a. matrix multiplication.Rewrite

as the trace of a bunch of transfer matrices multiplied together.

as the trace of a bunch of transfer matrices multiplied together.Similarly, rewrite the average spin

and the correlation function

and the correlation function  in terms of transfer matrices.

in terms of transfer matrices.

These quantities are best calculated in the eigenbasis of the transfer matrix. So our next steps are to

Express the partition function

in terms of eigenvalues and eigenstates of

in terms of eigenvalues and eigenstates of  . (dificulty: easy)

. (dificulty: easy)Express the average spin

in terms of eigenvalues and eigenstates of

in terms of eigenvalues and eigenstates of  . (difficulty: medium)

. (difficulty: medium)Express the correlation function

in terms of eigenvalues and eigenstates of

in terms of eigenvalues and eigenstates of  . (difficulty: Kivelson)

. (difficulty: Kivelson)

Afterwards, we will diagonalize the transfer matrix and explicitly calculate these quantities. Throughout these steps, we'll appeal to Pauli matrices and our intuition about the quantum mechanics of spin-half to help us calculate things.

Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the transfer matrix

Plug them in to find explicit expressions for

,

,  , and

, and  .

.Profit!?

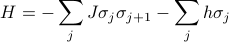

Writing the Hamiltonian as a sum over bonds

Our first step is to rewrite the Hamiltonian as a single sum over bonds, rather than two separate sums. Later on, we'll see that this form helps us neatly separate the partition function in a nice way.

The Hamiltonian was defined as

where the first term is the energy of each of the bonds between neighboring sites, and the second is the energy of each of the sites. Since we want to rewrite the Hamiltonian as a sum over bonds, we re-assign the energy of  'th site to its two neighboring bonds (bond

'th site to its two neighboring bonds (bond  to

to  , and

, and  to

to  ). (We also introduce a factor one-half to compensate for the fact that each site will now be counted twice). Now the Hamiltonian is sum over bonds

). (We also introduce a factor one-half to compensate for the fact that each site will now be counted twice). Now the Hamiltonian is sum over bonds

where  is the energy of the bond between sites

is the energy of the bond between sites  and

and  . (Note that

. (Note that  takes on four possible values, since there's four combinations of what the spins on sites

takes on four possible values, since there's four combinations of what the spins on sites  and

and  : ++, +-, -+, and --.)

: ++, +-, -+, and --.)

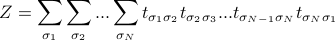

Defining the transfer matrix

With the Hamiltonian written in this form, we can calculate the partition function more easily.

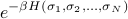

Remember that the partition function is the sum over all states of the Boltzmann weight  . Since the Hamiltonian

. Since the Hamiltonian  can be written as a sum, the Boltzmann weight

can be written as a sum, the Boltzmann weight  can be written as a product

can be written as a product

![= underbrace{left[e^{-beta E(sigma_1, sigma_2)}right]}_{t_{sigma_1sigma_2}} left[e^{- beta E(sigma_2, sigma_3)}right] ... left[e^{- beta E(sigma_N, sigma_1)}right]](eqs/6098972766548781087-130.png)

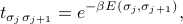

At this point we introduce the transfer matrix  as a notational trick to make the expression much look nicer. If we rename each of the factors in the product by defining

as a notational trick to make the expression much look nicer. If we rename each of the factors in the product by defining

then  looks like

looks like

ie, there's just a factor of  for each of the bonds in the Hamiltonian.

for each of the bonds in the Hamiltonian.

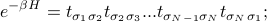

As another notational trick (remember this whole business with transfer matrices is sort of a notational trick anyways!), we can also rewrite the matrix entries of  in a quantum-mechanics-esque manner as

in a quantum-mechanics-esque manner as  . In this picture, we interpret the transfer matrix as an operator in the Hilbert space spanned by

. In this picture, we interpret the transfer matrix as an operator in the Hilbert space spanned by  and

and  . Since we're well versed with manipulating bras and kets from quantum mechanics, this alternative notation might be helpful for building our intution.

. Since we're well versed with manipulating bras and kets from quantum mechanics, this alternative notation might be helpful for building our intution.

Using this bra-ket notation, our expression for  now looks like

now looks like

This notation can be more enlightening, or more confusing, depending on your tastes! Personally, I like this bra-ket notation because my eyes are pretty bad and I find it annoying to squint at subscripts.

Interpreting the transfer matrix

The transfer matrix answers the question, if there's a bond between a spin  and another spin

and another spin  , then what is the value of

, then what is the value of  for that bond? Since there's two possibilities for the first spin

for that bond? Since there's two possibilities for the first spin  (+1 or -1) and two possibilities for the second spin

(+1 or -1) and two possibilities for the second spin  (+1 or -1), that means that

(+1 or -1), that means that  is a 2x2 matrix with four entries. (It's a funny sort of matrix where the indices take on values of

is a 2x2 matrix with four entries. (It's a funny sort of matrix where the indices take on values of  .)

.)

To be explicit, we can write the components of  as

as

![t = left[begin{array}{cc}t_{+1+1} & t_{+1-1} t_{-1+1} & t_{-1-1}end{array}right] = left[begin{array}{cc}e^{-beta E(+1,+1)} & e^{-beta E(+1,-1)} e^{-beta E(-1,+1)} & e^{-beta E(-1,-1)}end{array}right].](eqs/1990701643154741526-130.png)

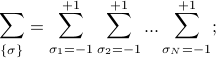

Rewriting the partition function as a trace

Now that we have a nice expression for  , we turn back to our task of finding the partition function

, we turn back to our task of finding the partition function  , which means we need to sum over all the possible configurations of the system. How do we do this?

, which means we need to sum over all the possible configurations of the system. How do we do this?

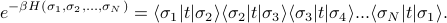

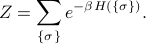

We need to sum over all possible configurations of the  spins; each spin can either be up or down, so there's a total of

spins; each spin can either be up or down, so there's a total of  configurations. Symbolically, we write this sum as

configurations. Symbolically, we write this sum as

that is, the first spin takes on values  , the second spin takes on values

, the second spin takes on values  , etc., and we're performing this sum for each of the

, etc., and we're performing this sum for each of the  spins. In class, Prof. Kivelson wrote a confusing expression with a product sign; personally, I'm not a fan. I think that expicitly writing out each of the summations is much more understandable.

spins. In class, Prof. Kivelson wrote a confusing expression with a product sign; personally, I'm not a fan. I think that expicitly writing out each of the summations is much more understandable.

Anyways, to find the partition function, we need to calculate

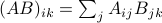

When we expand out the sum, we realize the key trick: the transfer matrices are matrix-multiplied with each other, because you sum over the repeated index.

Rememeber that matrix multiplication is defined as  . If we zoom in on the multiplication between the 1-2 transfer matrix and the 2-3 transfer matrix, we see that indeed, the transfer matrices are being multiplied by each other when we sum over their shared index

. If we zoom in on the multiplication between the 1-2 transfer matrix and the 2-3 transfer matrix, we see that indeed, the transfer matrices are being multiplied by each other when we sum over their shared index  :

:

So when we sum over spin #2, those two transfer matrices ‘‘collapse’’ together and we're left with a squared transfer matrix between spin #1 and spin #3.

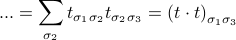

If we repeat this process of ‘‘collapsing’’ all the transfer matrices together, we end up with

which we recognize as the formula for the trace of  ,

,

![Z = textrm{Tr} left[t^Nright]!](eqs/5455956173591926392-130.png)

It's also possible to do this manipulation in the bra-ket notation. (Personally, I find this notation a bit more enlightening.) Remember that a matrix element  in bra-ket notation is written as

in bra-ket notation is written as  . If we use this notation, the partition function looks like

. If we use this notation, the partition function looks like

If we suggestively scooch the sum signs next to their respective ket-bras, it looks like

![Z = sum_{sigma_1} langle sigma_1 | t underbrace{left[sum_{sigma_2} | sigma_2 rangle langle sigma_2 | right]}_I t underbrace{left[sum_{sigma_3} | sigma_3 rangle langle sigma_3 | right ]}_I t ... t underbrace{left[ sum_{sigma_N}| sigma_N rangle langle sigma_N | right]}_I t | sigma_1 rangle](eqs/774378093776474918-130.png)

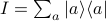

and we realize that there's just a copy of the identity lying between neighboring transfer matrix operators. (Remember the resolution of the identity  .)

.)

So  simplifies to

simplifies to

![Z = sum_{sigma_1} langle sigma_1 | t^N | sigma_1 rangle = textrm{Tr} left[t^Nright]](eqs/7694865124103242872-130.png)

as advertised.

Also, I can't help but to notice how familiar the expression for  looks! It's reminiscent of the propogator in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, where we split up the time evolution operator

looks! It's reminiscent of the propogator in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, where we split up the time evolution operator  into

into  chunks, and then sandwich a resolution of the identity between each of the chunks ;)

chunks, and then sandwich a resolution of the identity between each of the chunks ;)

Rewriting average spin as a trace

Now that we know how the partition function looks like, let's go on to compute the ensemble average of the spin,  . I'll be using the bra-ket notation since I find it hard to squint at all the puny subscripts.

. I'll be using the bra-ket notation since I find it hard to squint at all the puny subscripts.

As with all expectation values, we can calculate the expectation of  by summing up the value of

by summing up the value of  for each microstate, weighted by its probability. This has the form

for each microstate, weighted by its probability. This has the form

and if we plug in the Boltzmann weights for the probabilities  , our expression looks like

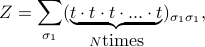

, our expression looks like

The sum looks quite similar to our expression for  earlier, with the exception of an extra factor of

earlier, with the exception of an extra factor of  . To see the effect of what that factor does, let's zoom in on everything that involves

. To see the effect of what that factor does, let's zoom in on everything that involves  inside the expression:

inside the expression:

How do we make sense of this expression? If there wasn't the factor of  , this would just be the resolution of the identity,

, this would just be the resolution of the identity,  , but it's not immediately obvious what the factor of

, but it's not immediately obvious what the factor of  does. Let me try explicitly writing out the sum:

does. Let me try explicitly writing out the sum:

![... = (+1) bigg[|+1 rangle langle +1 |bigg] + (-1) bigg[|-1 rangle langle -1 |bigg]](eqs/4288690582678485407-130.png)

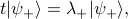

This is a matrix with +1 in the (+1,+1) entry and a -1 in the (-1,-1) entry. In other words, it's the Pauli z matrix  defined by

defined by

Now when we write out the transfer matrices in our sum, all the ket-bras resolve to the identity expect for the  'th one, which instead becomes a Pauli z matrix. So we end up with a

'th one, which instead becomes a Pauli z matrix. So we end up with a  trapped between a bunch of

trapped between a bunch of  's in our expression.

's in our expression.

![langle sigma_j rangle = sum_{sigma_1} langle sigma_1 | underbrace{t cdot ... cdot t}_{j-1} cdot tau_z cdot underbrace{t cdot ... cdot t}_{N-(j-1)} | sigma_1 rangle = textrm{Tr} left[t^{j-1} tau_z t^{N-(j-1)}right]](eqs/3944850711770817419-130.png)

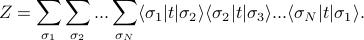

Rewriting the spin-spin correlation as a trace

When we find the spin-spin correlation function  , a very similar trick happens; you can work out the details for yourself.

, a very similar trick happens; you can work out the details for yourself.

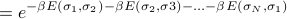

The end result is that

![begin{array}{rl} Z &= textrm{Tr} left[t^Nright], langle sigma_j rangle &= Z^{-1} textrm{Tr} left[t^{j-1} tau_z t^{N-(j-1)}right], langle sigma_i sigma_j rangle &= Z^{-1} textrm{Tr} left[t^{i-1} tau_z t^{j-i} tau_z t^{N-(j-1)}right], end{array}](eqs/7864856541006257332-130.png)

Calculating these traces

We still need to calculate these traces in terms of some basis. Remember from linear algebra that we can calculate traces in terms of any basis we want.

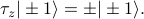

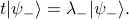

In our case, the best basis to use is the eigenbasis of the transfer matrix  . Since the transfer matrix is a real symmetric 2x2 matrix, it has two orthogonal eigenvectors that span its whole Hilbert space. We'll write these two eigenvectors and their corresponding eigenvalues as

. Since the transfer matrix is a real symmetric 2x2 matrix, it has two orthogonal eigenvectors that span its whole Hilbert space. We'll write these two eigenvectors and their corresponding eigenvalues as

We won't actually explicitly find these eigenvalues and eigenvectors just yet; I'll leave that for the next section because there's some neat tricks you can do with Pauli matrices by drawing an analogy to a spin-half particle. For now I want to pretend we know the eigenstates already, and just focus on the algebraic manipulations.

(Throughout this section I'll slip into quantum mechanics lingo, and say ‘‘operator’’ in place of ‘‘matrix’’ or ‘‘state’’ in place of ‘‘vector’’)

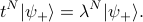

Simplifying the partition function

What's so nice about the eigenstates of  is that they make it much easier to find

is that they make it much easier to find  . When you apply an operator multiple times to an eigenstate, you just pull out an eigenvalue each time:

. When you apply an operator multiple times to an eigenstate, you just pull out an eigenvalue each time:

(Remember that  is an operator, but

is an operator, but  are just numbers.)

are just numbers.)

So if we use this basis to evaluate the partition function, it simplifies very nicely:

Since eventually we'll be taking the thermodynamic limit  , it's nice to rewrite this expression a bit to understand what happens when we take that limit. We find that

, it's nice to rewrite this expression a bit to understand what happens when we take that limit. We find that

![Z = lambda_+^N left[1 + left(frac {lambda_-}{lambda_+}right)^N right] longrightarrow lambda_+^N quad textrm{as}quad N to infty](eqs/3696132041728494562-130.png)

In the expression above,  is less than 1, so when we raise it to a huge power like

is less than 1, so when we raise it to a huge power like  , it goes to 0.

, it goes to 0.

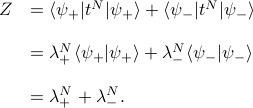

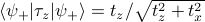

Simplifying the average spin

We can do something quite similar for finding the average spin

![langle sigma_j rangle = frac 1 Z textrm{Tr} left[t^{j-1} tau_z t^{N-(j-1)}right],](eqs/3803550988872497987-130.png)

which can be written explicitly in the eigenbasis of  as

as

![langle sigma_j rangle = frac 1 Z Bigg[bigglangle psi_+ bigg| t^{j-1} tau_z t^{N-(j-1)} bigg| psi_+ biggrangle + bigglangle psi_- bigg| t^{j-1} tau_z t^{N-(j-1)} bigg| psi_- biggrangleBigg].](eqs/3750875062634074248-130.png)

I'll describe in words what happens when we sandwich our eigenstates around the operator. The  copies of

copies of  to the left of the

to the left of the  can act backwards on the bra-eigenstate to pull out

can act backwards on the bra-eigenstate to pull out  powers of the eigenvalue (no complex conjugate since

powers of the eigenvalue (no complex conjugate since  is Hermitian with real eigenvalues!); the other

is Hermitian with real eigenvalues!); the other  copies of

copies of  to the right of

to the right of  act forwards on the ket-eigenstate to pull out another

act forwards on the ket-eigenstate to pull out another  powers of the eigenvalue. We're left with the

powers of the eigenvalue. We're left with the  trapped inside the sandwich:

trapped inside the sandwich:

![langle sigma_j rangle = frac 1 Z bigg[lambda_+^N langle psi_+ | tau_z | psi_+ rangle + lambda_-^N langle psi_- | tau_z | psi_- rangle bigg]](eqs/6605663749693089394-130.png)

Again, when we take  , only the first term survives, because the ratio of the terms

, only the first term survives, because the ratio of the terms  goes to 0. So we find that

goes to 0. So we find that

Diagonalizing the Transfer Matrix

Check out my answer on piazza, where I explain how to find the eigenvalues of  by decomposing it in terms of the Pauli matrices as

by decomposing it in terms of the Pauli matrices as  .

.

Check out the picture here for a graphical explanation of why  . A picture is worth a thousand words!

. A picture is worth a thousand words!

Work in progress, check back soon…

Our first problem set

To be honest, we pretty much did the problem set during class today.

On the problem set, Prof. Kivelson first asks us to calculate the magnetization density  , which we did in class (!). Later he asks us to express the transfer matrix in terms of Pauli matrices (which we also did in class (!?)) and to discuss the correspondence between the 1D Ising Model and a spin-half quantum system (again, we also did this in class!!!).

, which we did in class (!). Later he asks us to express the transfer matrix in terms of Pauli matrices (which we also did in class (!?)) and to discuss the correspondence between the 1D Ising Model and a spin-half quantum system (again, we also did this in class!!!).

It looks like the main purpose of the problem set is

to review everything from class today,

to gain a better intuition by interpreting the various limits of the magnetization density

, and

, andto apply our techniques from class to solve other systems like the

antiferromagnet (with both first and second neighbor interactions) or the X-Y ferromagnet (where each spin takes on an angle

antiferromagnet (with both first and second neighbor interactions) or the X-Y ferromagnet (where each spin takes on an angle  rather than a discrete

rather than a discrete  ).

).

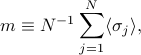

Anyways, I'm not sure how much I can discuss here without violating the honor code. But I did have an interesting remark on the definition of magnetization density.

tl;dr:  is a subtle statement.

is a subtle statement.

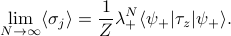

On the problem set, the magnetization density is defined as

which seems sort of bizarre since we add up  terms and then divide by

terms and then divide by  again. What's going on here?

again. What's going on here?

The answer has to do with intensive vs extensive quantities, and experimental observables vs mathematical expressions.

To start off, notice that the average of any particular microscopic spin  is impossible to measure! (Spin

is impossible to measure! (Spin  would have a puny magnetic field, and besides, there's a whole bunch of other spins nearby that would mess up the measurement.) Our actual experimental observable is not the magnetization of one particular spin, but rather the magnetization of the whole magnet, which is given by

would have a puny magnetic field, and besides, there's a whole bunch of other spins nearby that would mess up the measurement.) Our actual experimental observable is not the magnetization of one particular spin, but rather the magnetization of the whole magnet, which is given by

That is, when we perform an experiment, we measure the total magnetization of the magnet, which we get by adding up the contributions from each of the spins. (Notice this is capital  , not lowercase

, not lowercase  !)

!)

The problem with total magnetization  is that it's an extensive rather than intensive property – that is, it scales with the system size

is that it's an extensive rather than intensive property – that is, it scales with the system size  . If we doubled the size of the magnet, we would also double the total magnetiation

. If we doubled the size of the magnet, we would also double the total magnetiation  . Now, we don't want to use an extensive property that grows with

. Now, we don't want to use an extensive property that grows with  , since it'll blow up when we take the thermodynamic limit

, since it'll blow up when we take the thermodynamic limit  . Rather, we want to use an intensive property independent of system size, a density rather than a total quantity.

. Rather, we want to use an intensive property independent of system size, a density rather than a total quantity.

To solve this conundrum, just divide the total magnetization by  . We define the magnetization density

. We define the magnetization density  as

as

and voila,  no longer blows up as

no longer blows up as  . So we've achieved our goal of finding an experimental quantity that's intensive.

. So we've achieved our goal of finding an experimental quantity that's intensive.

Finally, just to make this whole affair even more ridiculous, it turns out that  is actually the same value for all

is actually the same value for all  ! (Remember, the Ising model Hamiltonian is translationally invariant.) So when we find

! (Remember, the Ising model Hamiltonian is translationally invariant.) So when we find  , we're just adding up the same number

, we're just adding up the same number  times, and then dividing by

times, and then dividing by  …and at the end of the day, the magnetization density is just the same as the average spin

…and at the end of the day, the magnetization density is just the same as the average spin  .

.