The Story

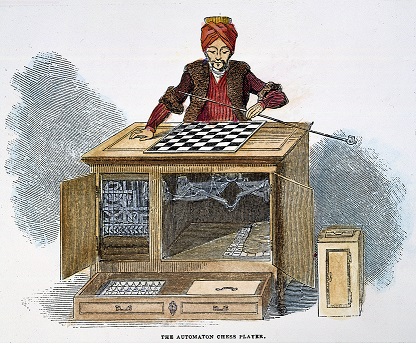

For much of modern history, chess playing has been seen as a "litmus test" of the ability for computers to act intelligently. In 1770, the Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen unveiled "The Turk", a (fake) chess-playing machine. Although the actual machine worked by allowing a human chess player to sit inside of it and decide the machine's moves, audiences around the world were fascinated by the idea of a machine that could perform intelligent tasks at the same level as humans.

With the advent of computers in the 1940s, researchers and hobbyists began the first serious attempts at making an intelligent chess-playing machine. In 1950, Claude Shannon published a groundbreaking paper entitled "Programming a Computer for Playing Chess", which first put forth the idea of a function for evaluating the efficacy of a particular move and a "minimax" algorithm which took advantage of this evaluation function by taking into account the efficacy of future moves that would be made available by any particular move. This work provided a framework for all future research in computer chess playing.

As was the case with many subfields of Artificial Intelligence at this time, progress in the development of chess-playing hardware lagged behind the theoretical frameworks developed in the 60s and 70s, building on Shannon's work. The public was doubtful that a machine would ever be able to defeat a proficient human chess player. Chessmaster and computer chess pioneer David Levy famously made the following statement in 1968: "Prompted by the lack of conceptual progress over more than two decades, I am tempted to speculate that a computer program will not gain the title of International Master before the turn of the century and that the idea of an electronic world champion belongs only in the pages of a science fiction book."

In the mid-1990s, however, the tides began to change. Despite the lingering skepticism of the chess community (when asked to confirm his belief that Garry Kasparov could beat any existing computer chess program, Levy stated, "I'm positive. I'd stake my life on it"), chess-playing computers began to beat extremely proficient chess players in exhibition matches. The turning point came in 1997, when Chessmaster Garry Kasparov faced off against IBM's chess-playing computer Deep Blue in New York, NY in an official match under tournament regulations. Despite having lost a previous match against Kasparov in 1996, Deep Blue won the 1997 match 3.5 to 2.5 and became the first computer program to defeat a world chess champion in match play.

Since the seminal 1997 victory, chess-playing computer programs have built upon Deep Blue's developments to become even more proficient and efficient. Nowadays, one can run chess programs even more advanced than Deep Blue on a standard desktop or laptop computer.

Claude Shannon

Garry Kasparov vs. Deep Blue

AI Techniques

Tree Search

The basic model of chess is that of a Tree Search problem, where each state is a particular arrangement of the pieces on the board and the available actions correspond to the legal chess moves for the current player in that arrangement. An example "slice" of such a tree is given in the following figure:

Once we have modeled the game in this way, we can begin applying our algorithms from this course to the problem!

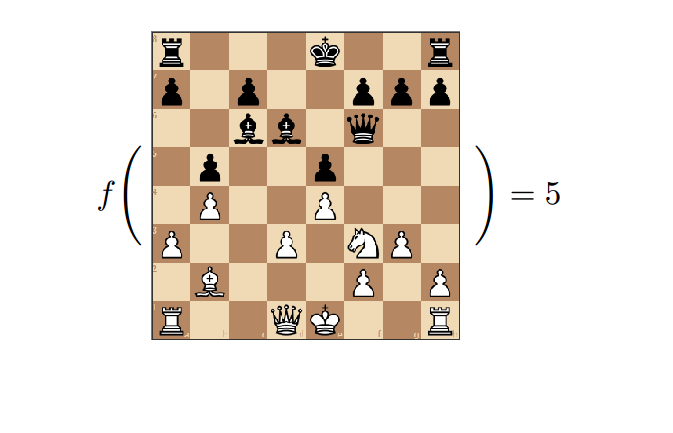

The Evaluation Function

As put forth in Shannon's paper, the primary ingredient in a chess-playing program is the evaluation function. Since we can't look forward all the way to the end of the game and see if a particular move will win (especially since we don't know what the other player will do during their turns!), we must create a function which takes in a state of the game (in our case, a board arrangement) and boils it down to a real-number evaluation of the state. For example, the function could give higher scores to board states in which the player of interest has more of their pieces on the board than the opponent. In particular, we would probably want the function to assign an extremely high score (perhaps even infinity) to the board arrangement in which the opponent's king is in checkmate, meaning that the player of interest is guaranteed to win the game.

The Minimax Algorithm

Given an evaluation, all that's left is a way of actually choosing which move to take. Although looking ahead one step and simply choosing the move which leads to the board arrangement with the highest evaluation score would be a good baseline, we can be even smarter and take into account the actions our opponent could take once we've moved. This intuition leads to the "Minimax algorithm", so-called because we choose the action which minimizes our maximum possible "loss" from making a particular move. Specifically, for each move we could make we look ahead as many steps as our computing power will allow and examine all the possible moves our opponent could make in each of their future turns, given that we've made our original move. We then take the maximum "loss" (equivalently, the minimum of our evaluation function) that our opponent could induce for us via their moves, and we choose the move we could make which minimizes this maximum.

Heuristics/Optimizations

Equipped with an evaluation function and an implementation of the minimax algorithm, one can already design an incredibly effective chess-playing program. However, the "big time" programs build even further upon these by implementing "heuristics", simple rules which can cut down on computation time, along with optimizations of the minimax algorithm, given the specific structure of chess. An example heuristic could be that if a move leads to the player's king being in checkmate, then the algorithm should not look any farther down that path of the game tree, since we know the player will never want to make that move. A popular optimization of minimax is known as Alpha-beta pruning, wherein any move for which another move has already been discovered that is guaranteed to do better than it is eliminated. For example, in the following tree we do not need to explore any of the paths whose edges are crossed-out, since we've already found moves we know will perform better:

Get Involved

If you want to work on similar problems, there are many great resources both on the internet and here at Stanford that you can take advantage of! Stanford professor Michael Genesereth has a course available on Coursera entitled "General Game Playing", which delves deeply into the algorithmic and logical foundations of chess-playing computer programs. If you are at Stanford, the course is offered as CS227B and is taught each Spring quarter. For a foray into the specific methods utilized by chess-playing programs, the aforementioned David Levy has a book encompassing a vast range of such techniques entitled "Computer Chess Compendium". Lastly, you should pay particular attention to the Search portion of this class, as almost all modern programs boil down to simple implementations of A* search and/or minimax search with fancy chess-specific heuristics and optimizations!