Lecture 8: Strings & Grids

July 1st, 2021

Today: black box, string loops, grid, grid testing

Reminders

Strings

For more detail, see guide Python Strings

len() function

>>> len('Hello')

5

>>> s = 'Hello' # Equivalently

>>> len(s)

5

>>> len('x')

1

>>> len('')

0

Empty String ''

Zero Based Indexing - Super Common

String Square Bracket Index

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[0] 'P' >>> s[1] 'y' >>> s[4] 'o' >>> s[5] 'n' >>> s[6] IndexError: string index out of range

String Immutable

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[0] # read ok 'P' >>> s[0] = 'X' # write not ok TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

String +

>>> a = 'Hello' >>> b = 'there' >>> a + b 'Hellothere' >>> a 'Hello'

1. Set Var With =

We've already used = to set a variable to point to a value, in this case pointing to the string 'hello'.

s = 'hello'

2. Change Var With =

What if we use = to set an existing variable to point to a new value? This just changes the variable to point to the latest value, forgetting the previous value. The assignment = could be translated to English as "now points to".

s = 'hello' # change s to point to 'bye' s = 'bye'

Black Box - Describing Code

Suppose there were a function named alpha_only(s), and we tried to describe it, talking about its code. Code has a lot of detail and complexity to it, so it's not a good way to characterize a function.

Black Box - Inputs and Outputs

Instead, we wall off the code, not looking inside the function. Instead, characterize the function by talking only about its input and output data - parameters and return value.

Black Box Design

Strings

Continue with strings. For more details, see the Python guide chapter on strings

Useful Pattern: s = s + something

>>> s = 'hello' >>> s = s + '!' >>> # Q: What is s now?

Answer: s is 'hello!' after the two lines. So s = s + xxx is a way of adding something to the right side of a string. The following form does the exactly the same thing using += as a shorthand:

>>> s = 'hello' >>> s += '!'

String Index Numbers

Here is our string, using zero-based index numbers to refer to the individual chars..

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[0] 'P' >>> s[1] 'y' >>>

How To Loop Over Those Index Numbers?

The length of the string is 6. The index numbers are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. How to write a loop that generates those numbers? It's the same loop we used to, say, loop over the x values of an image. If the image width was 100, we wanted the index numbers 0, 1, 2.. 99. Strings are exactly the same, feeding len(s) into the range() function.

Standard loop: for i in range(len(s)):

This is the standard, idiomatic loop to go through all the index numbers.

It's traditional to use a loop variable with the simple name i with this loop. Inside the loop, use s[i] to access each char of the string.

# have string s

for i in range(len(s)):

# access s[i] in here

1. double_char() Example

double_char(s): Given string s. Return a new string that has 2 chars for every char in s. So 'Hello' returns 'HHeelllloo'. Use a for/i/range loop.

Also, see the experimental server section string2 for many problems like double_char()

Solution code

def double_char(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

result = result + s[i] + s[i]

return result

Extra: not_ab()

not_ab(s): Given string s. Return a new string made of all the chars in s which are not lowercase 'a' or 'b'. Use a for/i/range loop.

Try to solve using for/i/range loop with the += pattern like double_char(). Test each char to see if it is 'a' or 'b' using !=.

> not_ab

String Testing: 'a' vs. 'A'

We've used == already. 'a' and 'A' are different characters.

>>> 'a' == 'A' False >>> s = 'red' >>> s == 'red' # two equal signs True >>> s == 'Red' # must match exactly False

String Testing - in

>>> 'c' in 'abcd' True >>> 'bc' in 'abcd' True >>> 'bx' in 'abcd' False >>> 'A' in 'abcd' False

String Character Class Tests

s.isdigit() - True if all chars in s are digits '0' '1' .. '9'

s.isalpha() - True for alphabetic word char, i.e. 'a-z' and 'A-Z'. Each unicode alphabet has its own definition of what's alphabetic, e.g. 'Ω' below is alphabetic.

s.isalnum() - alphanumeric, just combines isalpha() and isdigit()

s.isspace() - True for whitespace char, e.g. space, tab, newline

>>> 'a'.isalpha() True >>> 'abc'.isalpha() # works for multiple chars too True >>> 'Z'.isalpha() True >>> '$'.isalpha() False >>> '@'.isalpha() False >>> '9'.isdigit() True >>> ' '.isspace() True

Exercise: alpha_only(s)

Solution code

def alpha_only(s):

result = ''

# Loop over all index numbers

for i in range(len(s)):

# Access each s[i]

if s[i].isalpha():

result += s[i]

return result

if Variation: if / else

See guide for more if/else details: Python-if

if test-expr: Lines-A else: Lines-B

Example: str_dx()

> str_dx

Solution code

def str_dx(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

result += 'd'

else:

result += 'x'

return result

else vs. not

Sometimes beginners sort of back into using else to do something if the test is False, like this:

if some_test:

pass # do nothing here

else:

do_something

The correct way to do that is with not:

if not some_test:

do_something

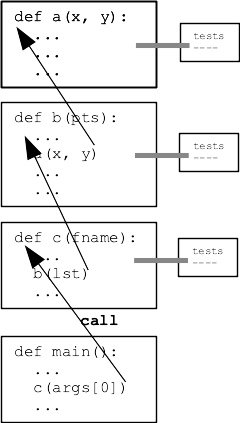

Big Picture - Program, Functions, Testing

Best Practices

str1 project

Python Function - Pydoc

def digits_only(s):

"""

Given a string s.

Return a string made of all

the chars in s which are digits,

so 'Hi4!x3' returns '43'.

Use a for/i/range loop.

(this code is complete)

>>> digits_only('Hi4!x3')

'43'

>>> digits_only('123')

'123'

>>> digits_only('')

''

"""

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

result += s[i]

return result

Python Function - Doctest

Here are the key lines that make one Doctest:

>>> digits_only('Hi4!x3')

'43'

Doctest - Important for Strategy

Divide and conquer - want to be able to divide your program up into separate functions, say A, B, and C. Want to work on one function at a time, including testing. Doctests make this really easy - just author the tests right next to where you write the code.

Doctest Workflow

We'll use Doctests to drive the examples in section and on homework-3. (Not on the quiz though)

Grid - Peeps Example

Today's grid example peeps.zip

Grid Utility Code

Grid Functions

Grid Example Code

grid = Grid(3, 2) grid.width # returns 3 grid.set(2, 0, 'a') grid.set(2, 1, 'b')

Grid Peeps Problem

Suppose we have a 2-d grid of peeps candy bunnies. A square in the grid is either 'p' if it contains a peep, or is None if empty. We'll say that a peep is "happy" if it has another peep immediately to its left or right.

Peep Happy

Look at the grid squares above. For each x,y .. is that a happy peep x,y?

x, y happy? (top row) 0, 0 -> False (no peep there) 1, 0 -> True 2, 0 -> True (2nd row, nobody happy) 0, 1 -> False 1, 1 -> False 2, 1 -> False

Peep Plan

Square Bracket Syntax for Grid

Here is the syntax for the above grid. The first [ .. ] is the first row, the second [ .. ] is the second row. This is fine for writing the data of a small grid, which is good enough for writing a test.

grid = Grid.build([[None, 'p', 'p'], ['p', None, 'p']])

Write is_happy() Doctests

def is_happy(grid, x, y):

"""

Given a grid of peeps and in bounds x,y.

Return True if there is a peep at that x,y

and it is happy.

A peep is happy if there is another peep

immediately to its left or right.

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 'p', 'p'], ['p', None, 'p']])

>>> is_happy(grid, 0, 0)

False

>>> is_happy(grid, 1, 0)

True

>>> is_happy(grid, 2, 0)

True

>>> is_happy(grid, 0, 1)

False

>>> is_happy(grid, 2, 1)

False

"""

pass

Write is_happy() Code

is_happy() Code v1

This code is fine. Using the "pick-off strategy, looking for cases to return True. Then return False as the bottom if none of the cases found another peep.

def is_happy(grid, x, y):

"""

Given a grid of peeps and in bounds x,y.

Return True if there is a peep at that x,y

and it is happy.

A peep is happy if there is another peep

immediately to its left or right.

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 'p', 'p'], ['p', None, 'p']])

>>> is_happy(grid, 0, 0)

False

>>> is_happy(grid, 1, 0)

True

>>> is_happy(grid, 2, 0)

True

>>> is_happy(grid, 0, 1)

False

>>> is_happy(grid, 2, 1)

False

"""

# 1. Check if there's a peep at x,y

# If not we can return False immediately.

if grid.get(x, y) != 'p':

return False

# 2. Happy because of peep to left?

# Must check that x-1 is in bounds before calling get()

if grid.in_bounds(x - 1, y):

if grid.get(x - 1, y) == 'p':

return True

# 3. Similarly, is there a peep to the right?

if grid.in_bounds(x + 1, y):

if grid.get(x + 1, y) == 'p':

return True

# 4. If we get to here, not a happy peep,

# so return False

return False

is_happy() Using and

The in_bounds() checks can be done with and instead nesting 2 ifs. This works because the "and" works through the tests left-to-right, and stops as soon as it gets a False. This code is a little shorter, but both approaches are fine.

# 2. Happy because of peep to left?

# here using "and" instead of 2 ifs

if grid.in_bounds(x - 1, y) and grid.get(x - 1, y) == 'p':

return True

Doctest Strategy

We're just starting down this path Doctests. Doctests enable writing little tests for each black-box function as you go, which turns out to be big productivity booster. We will play with this in section and on homework-3.