Lecture 20: Dictonaries and Lists 2.0

July 26th, 2021

Today: dict output, wordcount.py example program, list functions, List patterns, state-machine pattern

Dict Load-Up vs. Output

dict.keys()

>>> # Load up dict

>>> d = {}

>>> d['a'] = 'alpha'

>>> d['g'] = 'gamma'

>>> d['b'] = 'beta'

>>>

>>> # d.keys() - list-like "iterable" of keys, suitable for foreach etc.

>>> d.keys()

dict_keys(['a', 'g', 'b'])

>>>

>>> # d.values() - list of values, typically don't use this

>>> d.values()

dict_values(['alpha', 'gamma', 'beta'])

Common Bug with keys in a dictionary

>>> a_key = 'a' # make a variable for the key >>> d[a_key] = 'alpha' # use the variable instead of the literal >>> # notice there are no quotes around the name of the variable

Dict Output Code

Loop over d.keys(), for each key, look up its value. This works fine, the only problem is that the keys are in random order.

>>> for key in d.keys(): ... print(key, '->', d[key]) ... a -> alpha g -> gamma b -> beta

Dict Output sorted(d.keys())

>>> sorted(d.keys()) ['a', 'b', 'g'] >>> >>> for key in sorted(d.keys()): ... print(key, '->', d[key]) ... a -> alpha b -> beta g -> gamma

WordCount Example Code - Rosetta Stone!

The word count program is a sort of Rosetta stone of coding - it's a working demonstration of many important features of a computer program: strings, dicts, loops, parameters, return, decomposition, testing, sorting, files, and main(). The complete text of wordcount.py is at the end of this page for reference. Like you need to remember some bit of Python syntax, there's a good chance there's an example in this program. Or if you are learning a new computer language, you could try to figure out how to write wordcount in it to get started.

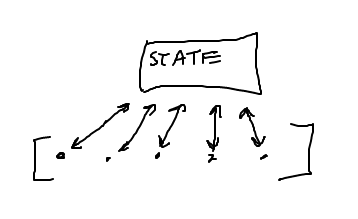

Wordcount Data Flow

Sample Run

Note how words are cleaned up

$ cat poem.txt Roses are red Violets are blue "RED" BLUE. $ $ python3 wordcount.py poem.txt are 2 blue 2 red 2 roses 1 violets 1

Dict-Count Code

def read_counts(filename):

"""

Given filename, reads its text, splits it into words.

Returns a "counts" dict where each word

is the key and its value is the int count

number of times it appears in the text.

Converts each word to a "clean", lowercase

version of that word.

The Doctests use little files like "test1.txt" in

this same folder.

>>> read_counts('test1.txt')

{'a': 2, 'b': 2}

>>> read_counts('test2.txt') # Q: why is b first here?

{'b': 1, 'a': 2}

>>> read_counts('test3.txt')

{'bob': 1}

"""

with open(filename) as f:

text = f.read() # demo reading whole string vs line/in/f way

# once done reading - do not need to be indented within open()

counts = {}

words = text.split()

for word in words:

word = word.lower()

cleaned = clean(word) # style: call clean() once, store in var

if cleaned != '': # subtle - cleaning may leave only ''

if cleaned not in counts:

counts[cleaned] = 0

counts[cleaned] += 1

return counts

Dict Output Code

In the wordcount.py .. the totally standard dict output code is used to print out the words and their counts.

def print_counts(counts):

"""

Given counts dict, print out each word and count

one per line in alphabetical order, like this

aardvark 1

apple 13

...

"""

for word in sorted(counts.keys()):

print(word, counts[word])

Timing Tests (optional)

Try more realistic files. Try the file alice-book.txt - the full text of Alice in Wonderland full text, 27,000 words. tale-of-two-cities.txt - full text, 133,000 words. Time the run of the program, see if the dic†/hash-table is as fast as they say with the command line "time" command. The second run will be a little faster, as the file is cached by the operating system.

$ time python3 wordcount.py alice-book.txt ... ... youth 6 zealand 1 zigzag 1 real 0m0.103s user 0m0.079s sys 0m0.019s

Here "real 0.103s" means regular clock time, 0.103 of a second, aka 103 milliseconds elapsed to run this command.

Windows PowerShell equivalent to "time" the run of a command:

$ Measure-Command { py wordcount.py alice-book.txt }

There are 33000 words in alice-book.txt. Each word hits the dict 3 times: 1x "in", then at least 1 get and 1 set for the +=. So how long does each dict access take?

>>> 0.103 / (33000 * 3) 1.0404040404040403e-06

So with our back-of-envelope math here, the dict is taking something less than 1 millionth of a second per access. In reality it's faster than that, as we are not separating out the for the file reading and parsing which went in to the 0.103 seconds.

Try it with tale-of-two-cities.txt which is 133000 words. This will better spread out the overhead, so get a lower time per access.

List 1.0 Features

See also Python guide Lists

>>> nums = [] >>> nums.append(1) >>> nums.append(0) >>> nums.append(6) >>> >>> nums [1, 0, 6] >>> >>> 6 in nums True >>> 5 in nums False >>> 5 not in nums True >>> >>> nums[0] 1 >>> >>> for num in nums: ... print(num) ... 1 0 6

List Slices

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c'] >>> lst2 = lst[1:] # slice without first elem >>> lst2 ['b', 'c'] >>> lst ['a', 'b', 'c'] >>> lst3 = lst[:] # copy whole list >>> lst3 ['a', 'b', 'c'] >>> # can prove lst3 is a copy, modify lst >>> lst[0] = 'xxx' >>> lst ['xxx', 'b', 'c'] >>> lst3 ['a', 'b', 'c']

lst.pop([optional index])

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c'] ['a', 'b', 'c'] >>> lst.pop() # opposite of append 'c' >>> lst ['a', 'b'] >>> lst.pop(0) # can specify index 'a' >>> lst ['b'] >>> lst.pop() 'b' >>> lst.pop() IndexError: pop from empty list >>>

List 2.0 Features

Below are other, less commonly used, list features. If a CS106A problem would use one of these, the problem statement will mention it.

Here are some "list2" problems on these if you are curious, but you do not need to do these.

> list2 exercises

lst.extend(lst2)

>>> a = [1, 2, 3] >>> b = [4, 5] >>> a.append(b) >>> # Q1 What is a now? >>> >>> >>> >>> a [1, 2, 3, [4, 5]] >>> >>> c = [1, 3, 5] >>> d = [2, 4] >>> c.extend(d) >>> # Q2 What is c now? >>> >>> >>> >>> c [1, 3, 5, 2, 4]

Alternative: lst1 + lst2

>>> a = [1, 2, 3] >>> b = [9, 10] >>> a + b [1, 2, 3, 9, 10] >>> a # original is still there [1, 2, 3]

lst.insert(index, elem)

>>> lst = ['a', 'b'] >>> lst.insert(0, 'z') >>> lst ['z', 'a', 'b']

lst.remove(target)

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'b']

>>> lst.remove('b')

>>> lst

['a', 'c', 'b']

List 2.0 Functions we will use

1. sorted()

>>> sorted([45, 100, 2, 12]) # numeric [2, 12, 45, 100] >>> >>> sorted([45, 100, 2, 12], reverse=True) [100, 45, 12, 2] >>> >>> sorted(['banana', 'apple', 'donut']) # alphabetic ['apple', 'banana', 'donut'] >>> >>> sorted(['45', '100', '2', '12']) # wrong-looking, fix later ['100', '12', '2', '45'] >>> >>> sorted(['45', '100', '2', '12', 13]) TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'int' and 'str'

2. min(), max()

>>> min(1, 3, 2) 1 >>> max(1, 3, 2) 3 >>> min([1, 3, 2]) # lists work 1 >>> min([1]) # len-1 works 1 >>> min([]) # len-0 is an error ValueError: min() arg is an empty sequence >>> min(['banana', 'apple', 'zebra']) # strs work too 'apple' >>> max(['banana', 'apple', 'zebra']) 'zebra'

sum()

Compute the sum of a collection of ints or floats, like +.

>>> nums = [1, 2, 1, 5] >>> sum(nums) 9

"State Machine" Pattern

When you're looking at a problem, you never want to think of it as this brand new thing you've never solved before. There's always parts of it that are idiomatic, or following some pattern you've seen before. The familiarity makes them easy to write, easy to read. We put in the pattern code where we can, adding needed custom code around it.

List Code Pattern Examples

Look at the "listpat" exercises on the experimental server

> listpat exercises

State-Machine Pattern

Previously: += Accumulate Result

Many functions we've done before actually fit the state-machine pattern, e.g. double_char(). We have a "result" set to empty before the loop. Something gets appended to result in the loop, possibly with some logic. We've used this with both strings (+=) and lists (.append).

# 1. init state before loop

result = ''

loop:

....

# 2. update state in the loop

if xxx:

result += yyy

# 3. Use state to compute result

return result

AKA "map"

With lists, this is sometimes called a "map" or "mapping", as the computation takes in a list length N of inputs, and computes an output list length N of outputs. We'll see this map idea again.

State-Machine "count" Strategy

# 1. init count to 0

count = 0

loop:

....

# 2. increment count in some cases

if xxx:

count += 1

# 3. Count is the answer after the loop

return count

Example: count_target()

count_target(): Given a list of ints and a target int, return the int count number of times the target appears in the list. Solve with a foreach + "count" variable.

Solution Code

def count_target(nums, target):

count = 0

for num in nums:

if num == target:

count += 1

return count

Extra: sumpat() - sum up list of ints, same pattern.

State-Machine Exercise: min()

> min()

Style note: we have Python built-in functions like min() max() len() list(). Avoid creating a variable with the same name as an important function, like "min" or "list". This is why our solution uses "best" as the variable to keep track of the smallest value seen so far instead of "min".

Slice note: one odd thing in this solution is that it use element [0] as the best initially, and then the loop will uselessly < compare best to element [0] on its first iteration. Could iterate over nums[1:] to avoid this useless comparison. But that would copy the entire list to avoid a single comparison, a bad tradeoff. Therefore it's better to just keep it as simple as possible, looping over the whole list in the standard way. Also, we prefer code with the correct answer that is readable, and our solution is good at both of those.

Solution

def min(nums):

# best tracks smallest value seen so far.

# Compare each element to it.

best = nums[0]

for num in nums:

if num < best:

best = num

return best

State-Machine - digit_decode()

Say we have a code where most of the chars in s are garbage. Except each time there is a digit in s, the next char goes in the output. Maybe you could use this to keep your parents out of your text messages in high school.

'xxyy9H%vvv%2i%t6!' -> 'Hi!'

How Might You Solve This?

I can imagine writing a while loop to find the first digit, then taking the next char, .. then the while loop again ... ugh.

Solution: State-Machine

Have a boolean variable take_next which is True if the next char should be taken (i.e. the char of the next iteration of the loop). Write a nice, plain loop through all the chars. Set take_next to True when you see a digit. For each char, look at take_next to see if it should be taken. The details of the code in the loop are subtle, hard to get right the first time. However, the bugs I would say are not hard to diagnose when you see the output. So just put some code in there and set about debugging it.

digit_decode() Solution

def digit_decode(s):

result = ''

take_next = False

for ch in s:

if take_next:

result += ch

take_next = False

if ch.isdigit():

take_next = True

# Set take_next at the bottom of the

# loop, taking effect on the next char

# at the top of the loop.

return result

State-Machine - "previous" Technique

Previous pattern:

# 1. Init with not-in-list value

previous = None

for elem in lst:

# 2. Use elem and previous in loop

# 3. last line in loop:

previous = elem

Previous Drawing

Here is a visualization of the "previous" strategy - the previous variable points to None, or some other chosen init value for the first iteration of the loop. For later loops, the previous variable lags one behind, pointing to the value from the previous iteration.

Example - count_dups()

count_dups(): Given a list of numbers, count how many "duplicates" there are in the list - a number the same as the value immediately before it in the list. Use a "previous" variable.

count_dups() Solution

The init value just needs to be some harmless value such that the == test will be False. None often works for this.

def count_dups(nums):

count = 0

previous = None # init

for num in nums:

if num == previous:

count += 1

previous = num # set for next loop

return count

(optional) State-Machine Challenge - hat_decode()

A neat example of a state-machine approach.

The "hat" code is a more complex way way to hid some text inside some other text. The string s is mostly made of garbage chars to ignore. However, '^' marks the beginning of actual message chars, and '.' marks their end. Grab the chars between the '^' and the '.', ignoring the others:

'xx^Ya.xx^y!.bb' -> 'Yay!'

Solving using a state-variable "copying" which is True when chars should be copied to the output and False when they should be ignored. Strategy idea: (1) write code to set the copying variable in the loop. (2) write code that looks at the copying variable to either add chars to the result or ignore them.

There is a very subtle issue about where the '^' and '.' checks go in the loop. Write the code the first way you can think of, setting copying to True and False when seeing the appropriate chars. Run the code. If it's not right (very common!), look at the got output. Why are extra chars in there?

For reference - source code for wordcount

WordCount Example Code

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Stanford CS106A WordCount Example

Juliette Woodrow

Counting the words in a text file is a sort

of Rosetta Stone of programming - it uses files, dicts, functions,

loops, logic, decomposition, testing, command line in main().

Trace the flow of data starting with main().

There is a sorted/lambda exercise below.

Code is provided for alphabetical output like:

$ python3 wordcount.py somefile.txt

aardvark 12

anvil 3

boat 4

...

**Exercise**

Implement code in print_top() to print the n most common words,

using sorted/lambda/items.

Then command line -top n feature calls print_top() for output like:

$ python3 wordcount.py -top 10 alice-book.txt

the 1639

and 866

to 725

a 631

she 541

it 530

of 511

said 462

i 410

alice 386

"""

import sys

def clean(s):

"""

Given string s, returns a clean version of s where all non-alpha

chars are removed from beginning and end, so '@@x^^' yields 'x'.

The resulting string will be empty if there are no alpha chars.

>>> clean('$abc^') # basic

'abc'

>>> clean('abc$$')

'abc'

>>> clean('^x^') # short (debug)

'x'

>>> clean('abc') # edge cases

'abc'

>>> clean('$$$')

''

>>> clean('')

''

"""

# Good examples below of inline comments: explain

# the *goal* of the lines, not repeating the line mechanics.

# Lines of code written for teaching often have more inline

# comments like this than regular production code.

# Move begin rightwards, past non-alpha punctuation

begin = 0

while begin < len(s) and not s[begin].isalpha():

begin += 1

# Move end leftwards, past non-alpha

end = len(s) - 1

while end >= begin and not s[end].isalpha():

end -= 1

# begin/end cross each other -> nothing left

if end < begin:

return ''

return s[begin:end + 1]

def read_counts(filename):

"""

Given filename, reads its text, splits it into words.

Returns a "counts" dict where each word

is the key and its value is the int count

number of times it appears in the text.

Converts each word to a "clean", lowercase

version of that word.

The Doctests use little files like "test1.txt" in

this same folder.

>>> read_counts('test1.txt')

{'a': 2, 'b': 2}

>>> read_counts('test2.txt') # Q: why is b first here?

{'b': 1, 'a': 2}

>>> read_counts('test3.txt')

{'bob': 1}

"""

with open(filename) as f:

text = f.read() # demo reading whole string vs line/in/f way

# once done reading - do not need to be indented within open()

counts = {}

words = text.split()

for word in words:

word = word.lower()

cleaned = clean(word) # style: call clean() once, store in var

if cleaned != '': # subtle - cleaning may leave only ''

if cleaned not in counts:

counts[cleaned] = 0

counts[cleaned] += 1

return counts

def print_counts(counts):

"""

Given counts dict, print out each word and count

one per line in alphabetical order, like this

aardvark 1

apple 13

...

"""

for word in sorted(counts.keys()):

print(word, counts[word])

# Alternately can use counts.items() to access all key/value pairs

# in one step.

# for key, value in sorted(counts.items()):

# print(key, value)

def print_top(counts, n):

"""

(Exercise)

Given counts dict and int n, print the n most common words

in decreasing order of count

the 1639

and 866

to 725

...

"""

items = counts.items()

# To get a start writing the code, could print raw items to

# get an idea of what we have.

# print(items)

# Your code here - our solution is 3 lines long, but it's dense!

# Hint:

# Sort the items with a lambda so the most common words are first.

# Then print just the first n word,count pairs

pass

items = sorted(items, key=lambda pair: pair[1], reverse=True) # 1. Sort largest count first

for word, count in items[:n]: # 2. Slice to grab first n

print(word, count)

def main():

# (provided)

# Command line forms

# 1. filename

# 2. -top n filename # prints n most common words

args = sys.argv[1:]

if len(args) == 1:

# filename

counts = read_counts(args[0])

print_counts(counts)

if len(args) == 3 and args[0] == '-top':

# -top n filename

n = int(args[1])

counts = read_counts(args[2])

print_top(counts, n)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()