Lecture 2: Control Flow

June 22nd, 2021

Today: insights about loops, if statement, ==, make-a-drawing, left_clear(), puzzles

Reminders

Lego Bricks!

Aside: Bit Controls

Aside: Checkmark / Diff Features

Here is the while-example we did last time, with some details added

Run go-green code

First we'll run the code. This code is complete. Watch it run a few times to see what the loop does, and we'll look at the details below.

> go-green

How Does a Loop Work?

The loop is a big increase in power, running lines many times. There are a few different types of loop. Here we will look at the while loop.

While - Test and Body

The while loop has two parts - the test expression which controls the looping, and the body contains the lines which are run again and again.

While Test

The first thing the while does is run the test code to see if the loop should run or not. In this case, the test is the code bit.front_clear() so we need to look at what that function does.

bit.front_clear()

bit.front_clear() Expression

The phrase bit.front_clear() here is an expression. An expression is a bit of code which runs as usual, and in addition returns a value to that spot in the code.

A common way to visualize how an expression works is drawing a diagonal arrow over the expression, showing the returned value sort coming out of the expression. Here is a drawing showing the boolean value coming out of the bit.front_clear() with bit not blocked and then blocked:

How the While Loop Works

go_green() Code

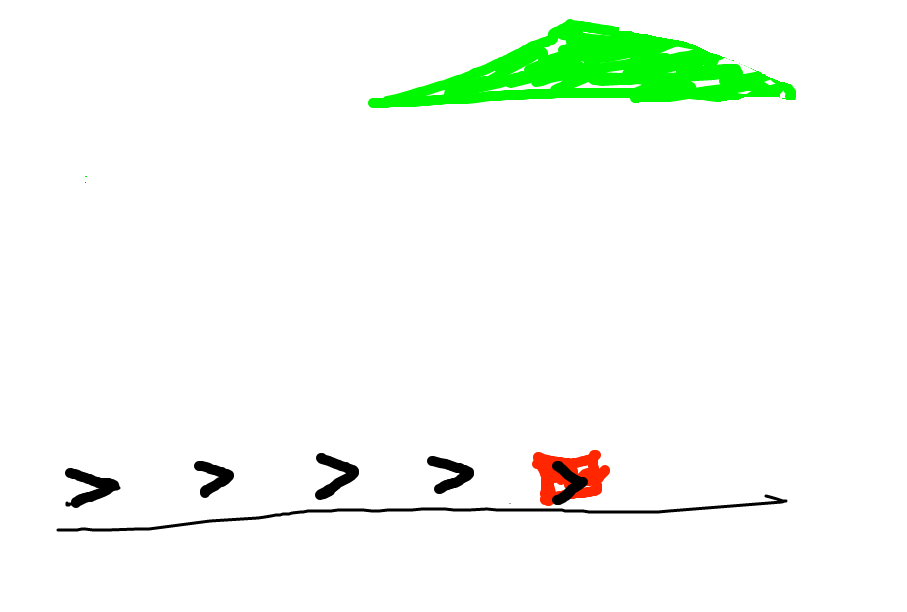

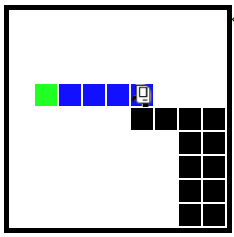

Looking at the go_green() code: while-test checks if front is clear. If the test is True, the loop body moves forward one square and paints it green. Then the loop automatically comes back to the top, and evaluates the test again. Eventually bit will move to the rightmost square, paint it green, and then loop back to check the test again. Sitting on that rightmost square, the test will return False and the loop will exit.

def go_green(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

Question: Line 5?

> go-green

Run the go-green code. Move the steps slider back so there are 2 un-painted squares and line 5 is hilighted.

Question: What line runs after line 5?

Look at the code and think about it. Then click the step button to advance the run to see what comes after line 5. It's the same every time, even the last time the loop runs.

Idiomatic Move-Forward Loop

Moving forward until blocked is a common pattern in bit problems, we'll use this code pattern to do something to each moved-to square.

...

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

# Do something to moved-to-square

...

Bit Loop Problems

There are a bunch of while-loop problems in here to play with - see the Bit Loop section on the server.

> Bit Loop

All Blue Example - Mine It For Observations

Bit starts in the upper left square facing the right side of the world. Move bit forward until blocked. Paint every square bit occupies blue, including the first. When finished, turn bit to face downwards. (Demo - this code is complete. Shows the basic while-loop with front_clear() to move until blocked, and also taking an action before and after the loop.)

all-blue() Code

def all_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

bit.paint('blue') # 1 paint before the loop

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right() # Turn after the loop

1. Run All Blue Normally, Test = Go

When a problem says "until blocked", you typically use front_clear() as the test. In the loop, the code moves forward one square, paints it blue.

Notice that the test of the while is essentially the "go" condition - when that test is true, Bit should move forward. Conversely, when the test is False, don't move. Keep the phrase "test = go" in mind, handy when thinking of code for a new problem.

2. First Square is Different

Since the loop does move-then-paint, it can't do the first square. We add a separate paint to do the first square. The while loop is not set up to do the first square, so we accept for many problems that we will need to add extra code before the loop if any action is needed for the first square.

3. Do Something After The Loop

Lines in the loop run many times. Lines before or after the loop run just once. In this case, to turn downwards after the loop: the line bit.right() is after the loop, and not indented within the loop.

4. Zero Loops is OK - Edge Cases

Look at Case-4, a world which is 1 square wide. Use the slider to go the start of this one, and step through the lines to see how the while-test behaves. In this case, the while-test is False the very first time! The result is, the body lines run zero times. This is fine actually. There were zero squares to move to, so looping zero times is perfect. This is an example of an "edge" case, the smallest possible input. It's nice that the while loop handles this edge case without any extra code.

5. Bad Move Bug

Let's do something wrong. Change the while-test to just True which is valid Python, it just doesn't work right for this problem. With this code, bit keeps going forward no matter what. Having a True test like this is a legitimate technique we'll use later, but here it is a bug.

...

while True: # BUG

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

The role of the while-test is to stop bit once there is a wall in front (i.e. front is not clear).

With this buggy code, the test is never False, so the loop never exits. Bit reaches the right side, but keeps trying to move(). Moving into a wall or black square (i.e. not a clear square) is an error, resulting in an error message like this:

Exception: Bad move, front is not clear, in:all_blue line 5 (Case 1)

If you see an exception like that, your code is doing a move() when the front is not clear You need to look at your code logic. Normally each move() has a front_clear() check before it, ensuring that the world has space for a move.

6. Infinite Loop Bugs

Infinite Loops

Infinite Loop 1 - Waggle Dance

Here is a buggy All Blue - instead of move() have bit do right() and the left() - a sort of "waggle dance" like bees do in the hive. Notice that .. bit never moves forward. Bit can do this for eternity, and never leave that first square! Everyone has days like that.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.right() # waggle dance!

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

Run the code - you will see a message about a timeout, suggesting that this code does not seem to reach an end.

Infinite Loop 2 - move vs. move()

Python syntax requires the parenthesis () to make a function call. Unfortunately, if you omit them, easy enough to do, it does not make a function call. So the code below looks right, but actually it's an infinite loop. Bit never moves. Try it yourself and see, then fix it.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move

bit.paint('blue')

Later Practice

After lecture, or if you get stuck on the homework, try some of the other problems in the "bit loop" section.

If Statement - Logic

While loop is power. If-statement is control, controlling if lines are run or not

If-Demo

We'll run this simple bit of code first, so you can see what it does. Then we'll look at the bits of code that go into it.

Problem statement: Move bit forward until blocked. For each moved-to square, if the square is blue, change it to green. (Demo: this code is complete.).

For reference here is the code:

def change_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

If Statement Syntax

Syntax 4 parts (similar to "while"): if, boolean test-expression, colon, indented body lines

if test-expression:

body lines

If Statement Operation

Look At Test Expression

Here are the key lines of code:

....

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

....

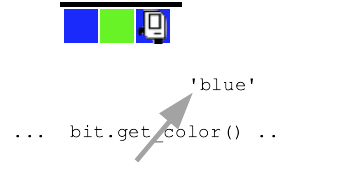

1. bit.get_color() Expression

Expression Visualization

Suppose bit is on a squared painted 'blue', as shown below. Here is diagram - visualizing that bit.get_color() is called and it's like there's an arrow coming out of it with the returned 'blue' to be used by the calling code.

2. == Compares Two Values - Boolean

Now Look at Change-Blue Again

Look at the if-statement. What is the translation of that into English? ..

For each moved-to square. If the square is blue, paint it green.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

Other Examples == !=

if bit.get_color() == 'red':

# run this if color is 'red'

if bit.get_color() == None:

# run this if square is not painted

if bit.get_color() != 'red':

# run this if square is anything but 'red'

# e.g. 'green' 'blue' or None

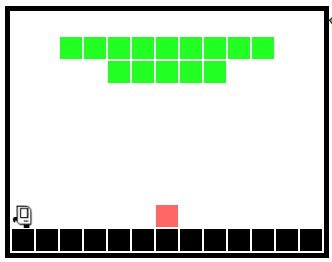

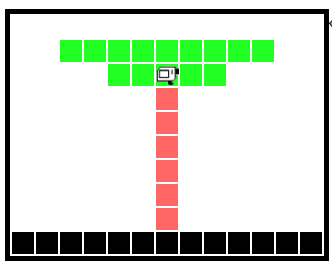

The Fix Tree Problem

This is a challenging problem for where we are at this point. Just watch (and you can do it in parallel) as I work through the problem to see the thinking and coding process in action.

Note: it is very common to move bit with an until-blocked loop. This problem is a little unusual, moving bit until hitting a particular color.

> Fix Tree

Before:

After:

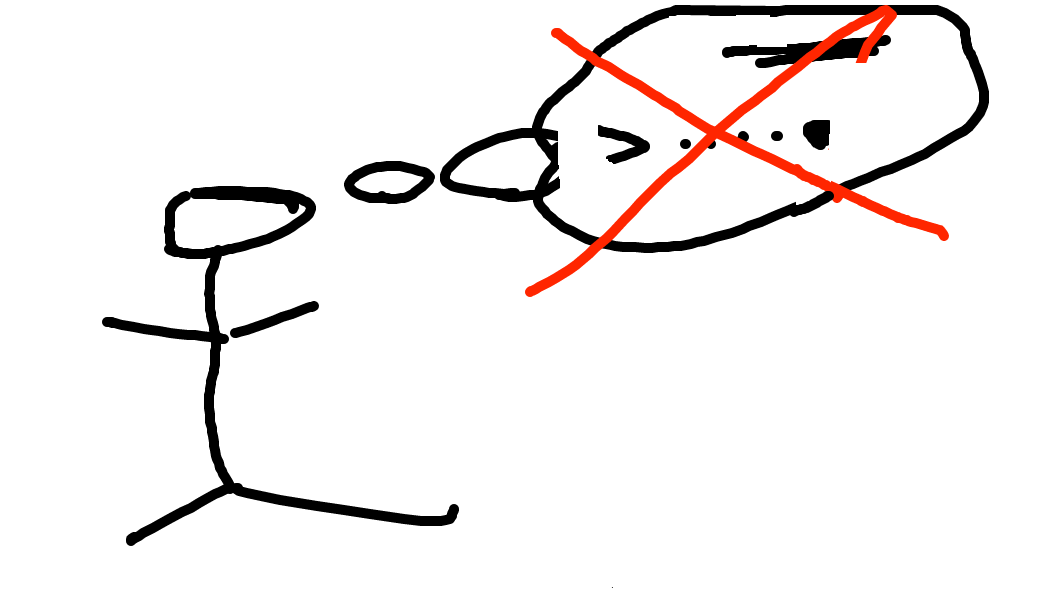

Important Ideas - Thinking Drawing and Coding

We have art for these. No expense has been spared!

1. Don't do it in your head

Don't do it just in your head - too much detail. Need to be able to work gradually and carefully.

2. Make a Drawing

Draw a typical "before" state.

3. What is a next-step goal - what would that look like?

Look at the before state - what code can advance this?

4. Question: what code?

You have the current state. What code could advance things to the next goal?

Q: Look at those bit positions. When do you want bit to move, and when not to move?

A: Want bit to move when the square is not red. What is the code for that?

Aside: if you were talking to a human, you would just say "make it look like this" and point to the goal. But not with a computer! You need to spell out the concrete steps to make the goal for the computer.

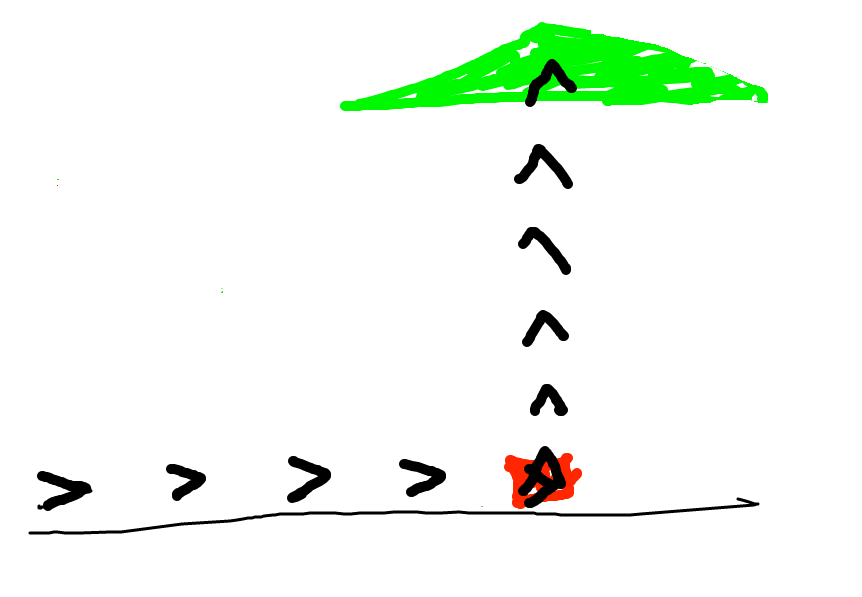

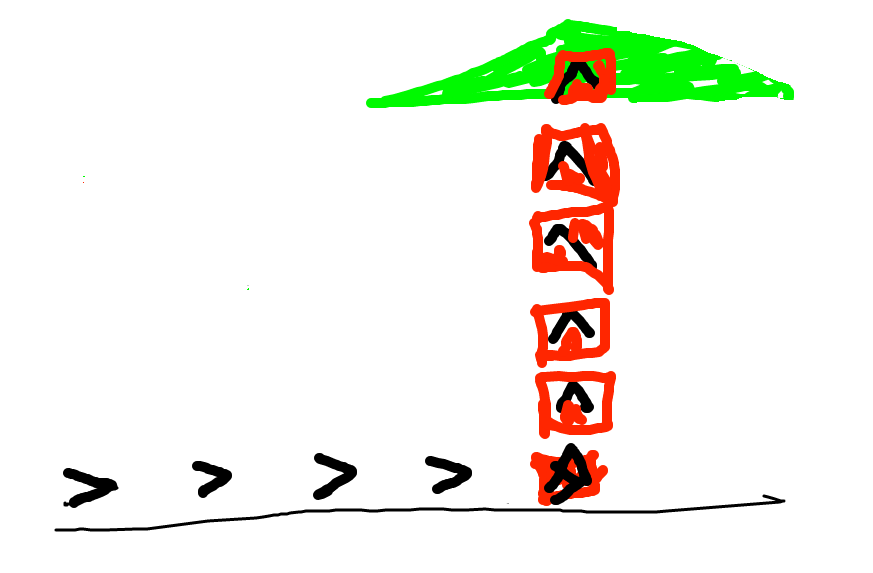

In this, case we're thinking while-loop. Draw in the various spots

bit will be in. What is a square where we do not want bit to move?

When bit is on the red square. Otherwise bit should move. What does that look

like in code?

Code looks like...

while bit.get_color() != 'red':

bit.move()

5. Try The Code, See What It Does

Ok, run it and see. Sometimes it will not do what we thought.

6. Ok what is the next goal.

Ok what is the next goal? What would be code to advance to that?

I think a reasonable guess here is similar to the first loop, but painting red, like this

while bit.get_color() != 'green':

bit.move()

bit.paint('red')

7. OOPS Not What Expected!

OOPS, that code looks reasonable, but does not do what we wanted. The question is: what sequence of actions did the code take to get this output? That's a better question than "why doesn't this work".

Go back to our drawing. Think about the paint/red and the while loop, how they interact.

8. Solution

The problem is that we paint the square red, and then go back to the loop test that is looking for green, which we just obliterated with red. One solution: add an if-statement, only paint blank squares red, otherwise leave the square alone.

That gives us this solution, which works perfectly..

def fix_tree(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.get_color() != 'red':

bit.move()

bit.left()

while bit.get_color() != 'green':

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == None:

bit.paint('red')

9. Thinking - Drawing - Coding

Use a drawing to think through the details of what the code is doing. It's tempting to just stare at the code and hit the Run button a lot! That doesn't work! Why is the code doing that?

Or put another way, in office hours, a very common question from the TA would be: can you make a little drawing of the input here, and then look at your line 6, and think about what it's going to do. All the TA does is prompt you to make a drawing and then use that to think about your code.

More Bit Tests: bit.left_clear() + not

if bit.left_clear():

# run here if left is clear

if not bit.left_clear():

# run here if left is blocked, aka not-clear

Server: Bit Puzzles

On the experimental server, the Bit Puzzles section has many problems where bit is in some situation and needs to move around using Python code. We'll look at the Coyote problems, and there are many more problems for practice.

Reverse Coyote, remember Test = Go

> reverse-coyote (while + right_clear)

Based on the RoadRunner cartoons, which have a real lightness to them. In the cartoons, the coyote is always running off the side of the cliff and hanging in space for a moment. For this problem, the coyote tries to run back onto the cliff before falling.

Before:

After:

Q: What is the while test for this? Remember that Test = Go. What is the test that is True when we want to move, and False when do not want to move?

A: bit.right_clear()

Then students can try the standard_coyote(), or climb() which is a little more difficult.

Probably not getting to this today, we'll do it Wednesday.

Decomposition - Program and Functions

"Divide and Conquer" - a classic strategy, works very well with computer codeFunctions - The Wizard of EarthSea

In the Wizard of EarthSea novels by Ursula Le Guin .. each thing in the world has its secret, true name. A magician calls a thing's true name, invoking that thing's power. Strangely, function calls work just like this - a function has a name and you call the function using its name, invoking its power.

How To Call a Function

We've seen def many times - defines a function. Recall that

a function has a name and body lines of code, like this "go_west" function:

def go_west(bit):

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

...

1. Call by noun.verb

To "call" a function means to go run its code, and there are two common ways it is done in Python. One way to call a function in Python is the "object oriented" form, aka noun.verb. The bit functions use this method, e.g. bit.left(), where "left" is the name of the function.

2. Call by name

The other way to call a function, which we will use here, is simply writing its name with parenthesis after it. For the above function named "go_west", code to call it looks like:

...

go_west(bit)

...

Both of these function-call styles are widely used in Python code.

What Does Function Call Do?

Say the program is running through some lines, which we'll call the "caller" lines. Then the run gets to the following function call line; what happens?

# caller lines

bit.right()

go_west(bit) # what does this do?

bit.left()

...

What the go_west(bit) directs the computer to do: (a) go run the lines inside the "go_west" function, suspend running here in the caller. (b) When go_west() is done, return to this exact spot in the caller lines and continue running with the next line. In other words, the program runs one function at a time, and function-call jumps over to run that function.

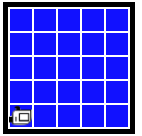

Fill World Blue Example

This example demonstrates bit code combined with divide-and-conquer decomposition.

The whole program does this: bit starts at the upper left facing down. We want to fill the whole world with blue, like this

Program Before:

Program After:

1. - Decompose fill_row_blue() "helper" function

First we'll decompose out a fill_row_blue() function that just does 1 row.

This is a "helper" function - solves a smaller sub-problem.

fill_row_blue() Before (pre)

fill_row_blue After (post):

You could write the code for this one, but we're providing it today to get to the next part.

Run the fill_row_blue a few times, see what it does.

Function Pre/Post Conditions

Pre/Post - Why Do I Care?

Look at fill_row_blue() Function

def fill_row_blue(bit):

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right()

bit.right()

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.left()

-Now comes the key, magic step for today. First, know what fill_row_blue() does exactly, pre/post.