Lecture 17: Better Code and String Functions

July 20th, 2021

Today: Idiomatic phrases, "reverse" chronicles, Better/shorter code invariant, more string functions, unicode

Today - Better / Shorter / Cleaner

Today, I'll show you some techniques where we have code that is already correct, but we can write it in a better, shorter way. It's intuitively satisfying to have a 10 line thing, and shrink it down to 6 lines that reads better.

Technique: Build on Idiomatic Phrases

You can think of every program as having some phrases of stock, idiomatic code, and then some phrases that are custom, idiosyncratic bits particular to that algorithm. We'll just say, use the idiomatic bits where they come up — easy to type in, easy to understand. Build your needed changes around the idiomatic code. The first 3 reverse() solutions below work in this way.

The "Reverse" Rosetta Stone

> Reverse problems

How many ways can you think of to reverse a string in Python? A sort of parlor trick to see a series of python techniques worked out, compare them.

'Hello' -> 'olleH'

Aside: there is a scene in the Movie Amadeus where Motzart plays a piece one way, then gets under the piano, reaches hands up and plays it again upside down. I believe today this would be called a "flex"? In any case, it is reminiscent of the problem here of taking the normal thing and dong it backwards. youtube

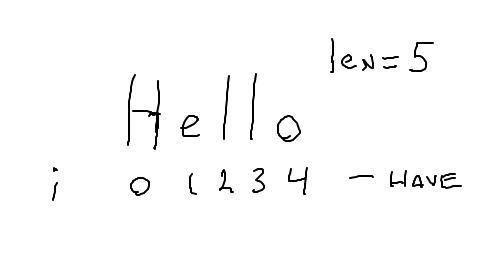

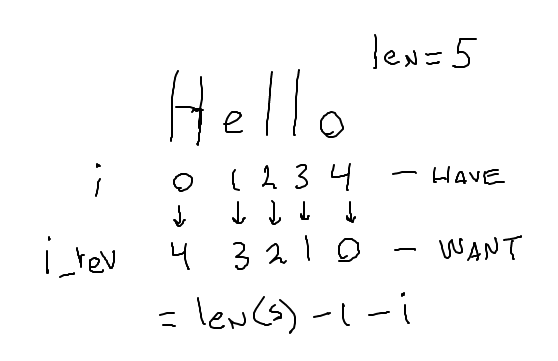

reverse1() - Muggle i_rev

We are very familiar with the idiomatic for i in range(len(s)), running i through the index numbers from start to end: 0, 1, 2, ... len-1. Start with that idiomatic loop. Think about computing an i_rev from each i, which will go through the string backwards: the last char, then the next to last, and so on. There turn out to be easier ways, but this is a reasonable approach.

I think of this as the "muggle" solution - using intricate devices to get the effect where there are easier ways. We could give this full credit, possibly pointing out the easier ways to do it.

Sketch out the idea on this drawing

Something like this:

reverse2() - reversed()

Using the well known, idiomatic for i in range(len(s)) is a good idea. The reversed() function is less well known, yielding a sequence in reverse order, but here it solves the problem very neatly.

reverse3() - +=

There's a very neat way to solve this using just the plain old for ch in s loop. Think about how you might re-write the += line. This is perhaps the most elegant, if non-obvious, solution, as it is short and uses simple Python features.

reverse4() - while

Instead of reversed() and range(), could write a while loop to manually generate the index numbers in the order we want. This is no longer a great solution - doing manually something that range() and reversed() provide for free.

reverse5 and reverse6

These are more silly uses of Python techniques, although they are code patterns we will cover later in CS106A, so we can check these out then.

Technique: Better/Shorter - Unify Cases

> Better problems

Shorter Code - Better Code

Unify Cases with a Variable

speeding() Example

speeding(speed, birthday): Compute speeding ticket fine as function of speed and birthday boolean. Rule: speed under 55, fine is 100, otherwise 200. If it's your birthday, the allowed speed is 5 mph more. Challenge: change this code to be shorter, not have so many distinct paths.

The code below works correctly. You can see there is one set of lines each for the birthday/not-birthday cases. What exactly is the difference between these two sets of lines?

def speeding(speed, birthday):

if not birthday:

if speed < 50:

return 100

else:

return 200

else: # is birthday

if speed < 55:

return 100

else:

return 200

Unify Cases Solution

speeding() Better Unified Solution

def speeding(speed, birthday):

# Set limit var

limit = 50

if birthday:

limit = 55

# Unified: limit holds value to use.

# One if-stmt handles all cases

if speed < limit:

return 100

return 200

def match(a, b):

result = ''

# Set length to whichever is shorter

length = len(a)

if len(b) < len(a):

length = len(b)

for i in range(length):

if a[i] == b[i]:

result += a[i]

return result

ncopies() Demo/Exercise

Change this code to be better / shorter. Look at lines that are similar - make an invariant.

ncopies(word, n, suffix): Given name string, int n, suffix string, return

n copies of string + suffix.

If suffix is the empty string, use '!' as the suffix.

Challenge: change this code to be shorter,

not have so many distinct paths.

Before:

def copies(word, n, suffix):

result = ''

if suffix == '':

for i in range(n):

result += word + '!'

else:

for i in range(n):

result += word + suffix

return result

ncopies() Unified Solution

Solution: use logic to set "suffix" to hold the suffix to use for all cases. Later code just uses suffix vs. separate if-stmt for each case.

def copies(word, n, suffix):

result = ''

# Set suffix if necessary to value to use

if suffix == '':

suffix = '!'

# Unified: one loop, using suffix

for i in range(n):

result += word + suffix

return result

String - More Functions

See guide for details: Strings

Thus far we have done String 1.0: len, index numbers, upper, lower, isalpha, isdigit, slices, .find().

There are more functions. You should at least have an idea that these exist, so you can look them up if needed. The important strategy is: don't write code manually to do something a built-in function in Python will do for you. The most important functions you should have memorized, and the more rare ones you can look up.

s.startswith() s.endswith()

These are very convenient True/False tests for the specific case of checking if a substring appears at the start or end of a string. Also a pretty nice example of function naming.

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Py')

True

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Px')

False

>>> 'resume.html'.endswith('.html')

True

String - replace()

>>> s ='this is it'

>>> s.replace('is', 'xxx') # returns changed version

'thxxx xxx it'

>>>

>>> s.replace('is', '')

'th it'

>>>

>>> s # s not changed

'this is it'

Recall: s.foo() Does Not Change s

Recall how calling a string function does not change it. Need to use the return value...

# NO: Call without using result:

s.replace('is', 'xxx')

# s is the same as it was

# YES: this works

s = s.replace('is', 'xxx')

String - strip()

>>> s = ' this and that\n' >>> s.strip() 'this and that'

String - split()

>>> s = '11,45,19.2,N'

>>> s.split(',')

['11', '45', '19.2', 'N']

>>> 'apple:banana:donut'.split(':')

['apple', 'banana', 'donut']

>>>

>>> 'this is it\n'.split() # special whitespace form

['this', 'is', 'it']

String - join()

>>> foods = ['apple', 'banana', 'donut'] >>> ':'.join(foods) 'apple:banana:donut'

String - format()

>>> 'Alice' + ' got score:' + str(12) # old: + and str()

'Alice got score:12'

>>>

>>> '{} got score:{}'.format('Alice', 12) # new: format()

'Alice got score:12'

>>>

String Unicode

In the early days of computers, the ASCII character encoding was very common, encoding the roman a-z alphabet. ASCII is simple, and requires just 1 byte to store 1 character, but it has no ability to represent characters of other languages.

Each character in a Python string is a unicode character, so characters for all languages are supported. Also, many emoji have been added to unicode as a sort of character.

Every unicode character is defined by a unicode "code point" which is basically a big int value that uniquely identifies that character. Unicode characters can be written using the "hex" version of their code point, e.g. "03A3" is the "Sigma" char Σ, and "2665" is the heart emoji char ♥.

Hexadecimal aside: hexadecimal is a way of writing an int in base-16 using the digits 0-9 plus the letters A-F, like this: 7F9A or 7f9a. Two hex digits together like 9A or FF represent the value stored in one byte, so hex is a traditional easy way to write out the value of a byte. When you look up an emoji on the web, typically you will see the code point written out in hex, like 1F644, the eye-roll emoji 🙄.

You can write a unicode char out in a Python string with a \u followed by the 4 hex digits of its code point. Notice how each unicode char is just one more character in the string:

>>> s = 'hi \u03A3' >>> s 'hi Σ' >>> len(s) 4 >>> s[0] 'h' >>> s[3] 'Σ' >>> >>> s = '\u03A9' # upper case omega >>> s 'Ω' >>> s.lower() # compute lowercase 'ω' >>> s.isalpha() # isalpha() knows about unicode True >>> >>> 'I \u2665' 'I ♥'

For a code point with more than 4-hex-digits, use \U (uppercase U) followed by 8 digits with leading 0's as needed, like the fire emoji 1F525, and the inevitable 1F4A9.

>>> 'the place is on \U0001F525' 'the place is on 🔥' >>> s = 'oh \U0001F4A9' >>> len(s) 4

Unicode and Ethics

The history of ASCII and Unicode is an example of ethics.

ASCII

In the early days of computing in the US, computers were designed with the ASCII character set, supporting only the roman a-z alphabet. This hurt the rest of the planet, which mostly doesn't write in English. There is a well known pattern where technology comes first in the developed world, is scaled up and becomes inexpensive, and then proliferates to the developing world. Computers in the US using ASCII broke that technology pipeline. Choosing a US-only solution was the cheapest choice for the US in the moment, but made the technology hard to access for most of the world.

Unicode Technology

Cost per byte aside, Unicode is a better solution - a freely available available standard. If a system uses Unicode, it and its data can interoperate with the other Unicode compliant systems - demonstrating the value created by a standard vs. having a bunch of incompatible systems.

Unicode vs. RAM Costs vs. Moore's Law

The cost of supporting non-ASCII data can be related to the cost of the RAM to store the unicode characters. In the 1950's every byte was literally expensive. An IBM model 360 could be leased for $5,000 per month, non inflation adjusted, and had about 32 kilobytes of RAM (not megabytes or gigabytes .. kilobytes!). So doing very approximate math, figuring RAM is half the cost of the computer, we get a cost of about $1 per byte per year.

>>> 5000 * 12 / (2 * 32000) 0.9375

If your modern computer with 8 GB of RAM had the same costs, it would cost 16 billion dollars to lease for one year! Fortunately we have Moore's law!

A unicode character that required 2 or 4 bytes was quite unattractive with those prices, if ASCII could do it for one byte. Of Course Unicode had not been invented yet, and the price of RAM is part of why.

Cheaper RAM via Moore's Law

Say 30 years later when Unicode became more common. Using double-every-2-years Moore's law as an estimate, 30 years = 15 doublings.

>>> 2 ** 15 32768

So RAM is on the order of 32,000 times cheaper by the 1990s. The costs don't track Moore's law exactly, but that gives you the idea. Anyway, adopting Unicode was the ethical and efficient thing to do, allowing software, files etc. to work across languages and across the world. The plummeting price of the extra RAM required no doubt helped move things along. Unicode is a better solution than ASCII, but it still doesn't have all the characters people around the world want to use when computing. Maybe someone will come up with a better system someday soon.

Unicode - A Cost and a Benefit

Python using Unicode is not just a cost to Python, it is also a benefit: Python is maintained by programmers from all over the world with many native languages. In fact, Guido van Rossum who created Python is from the Netherlands.

Suppose Python did not support Unicode. Would each country maintain a country or language-specific computer language instead of Python, so you end up with many python-like languages, each needing to be maintained? What in an incredible waste that would be. Instead, we have the one Python language, and people in many countries contribute to it, and all the users benefit from that huge, unified pool of contributors.

Python Open Source

Note that Python is free, open-source software. Anyone is free to use it. People contribute back improvements to the language, which are then shared back to everyone. The open-source model of software development is extremely widespread and successful in computer systems, so we may explain it in more detail later. It is a surprising model.

Hardware

Look at hardware from last lecture: lecture-16 - hardware