Lecture 12: Lists

July 12th, 2021

Today: string in/not-in, foreach, start lists, how to write main()

Patterns

When writing a new function, it's natural to draw upon similar functions you have written before. In CS, this is called the "patterns" strategy. You can quickly type in the common part of the pattern, and that code is familiar and easy and reliable. Then concentrate on what is different about the problem at hand.

Accumulate Pattern

For strings we have used an "accumulate" pattern many times. Start art off with the empty string, add something to the end of the result string in the loop.

result = '' loop result += something return result

Quick Return Pattern

Example: first_alpha()

> first_alpha() (in string3 section)

Given a string s, return the first alphabetic char in s, or None if there is no alphabetic char. Demonstrates quick-return pattern.

We are not building a whole new string. In this case, we're finding one char in the string and returning it.

'123abc' -> 'a' '123-456' -> None

1. Hinges on the fact that return exits the function immediately, so we can nest the return inside a loop or if-statement, structured to return a result immediately if the code finds one.

2. If the code gets to the end of the loop, the condition was never found. In other words, the loop never hits a true test. So what can we conclude about the string? In this case, there are no alpha chars in the string.

first_alpha() Solution

def first_alpha(s):

for i in range(len(s)):

# 1. Return immediately if found

if s[i].isalpha():

return s[i]

# 2. If we get here,

# there was no alpha char.

return None

Optional Exercise: has_digit()

'abc123' -> True

'abc' -> False

Use quick-return strategy, returning True or False.

Given a string s, return True if there is a digit in the string somewhere, False otherwise.

Solution - same pattern as first_alpha(), but returns boolean instead of a char

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

# 1. Exit immediately if found

return True

# 2. If we get here,

# there was no digit.

return False

More String Features - String4

On server see String4 - examples of features below: "foreach" and "in"

Recall: String in Test

>>> 'c' in 'abcd' True >>> 'bc' in 'abcd' # works for multiple chars True >>> 'bx' in 'abcd' False >>> 'A' in 'abcd' # upper/lower are different False

Variant: not in

The form not in inverts the in test, True if the substring is not in the big thing. This is readability feature, as "not in" reads very naturally in the code. The "not in" form is preferred for expressing this sort of not-in-there test.

>>> 'x' not in 'abcd' True >>> 'bc' not in 'abcd' False

Say for example we have a string of bad_chars, and we want to print a char if it is not bad. Using the "not in" form, the code reads nicely.

if ch not in bad_chars:

print(ch)

We could use regular "in", and then add a "not" to its left, like the following form. This works, but the "not in" form is the preferred style and reads better.

if not ch in bad_chars:

print(ch)

We've Had a Good Run: for i in range(len(s)):

Good old for/i/range .. we've gotten a lot of use out of that to loop over the index numbers for a collection. But there's a new sherif in town!

Loop over chars: for ch in s:

for ch in s:

# use ch in here,

# will be one char from s

Example: double_char2()

Like earlier double_char, but using foreach.

Solution

def double_char2(s):

result = ''

for ch in s:

result = result + ch + ch

return result

Example: difference(a, b)

Demonstrates both foreach and in

difference(a, b): Given two strings, a and b. Return a version of a, including only those chars which are not in b. Use case-sensitive comparisons. Use a for/ch/s loop.

Solution

def difference(a, b):

result = ''

# Look at all chars in a.

# Check each against b.

for ch in a:

if ch not in b:

result += ch

return result

Optional Exercise: intersect2(a, b)

Python Lists

See the guide: Python List for more details about lists

Lists are like Strings

Examples on Server list1

See the "list1" examples on the experimental server

1. List Literal: [1, 2, 3]

Use square brackets [..] to write a list in code (a "literal" list value), separating elements with commas. Python will print out a list value using this same square bracket format.

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> lst ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>>

"empty list" is just 2 square brackets with nothing within: []

2. Length of list: len(lst)

Use len() function, just like string. As a nice point of consistency, many things that work on strings work the same on lists - they are after all both linear collections using zero-based indexing.

>>> len(lst) 4

3. Square Brackets to access/change element

Use square brackets to access an element in a list. Valid index numbers are 0..len-1. Unlike string, can assign = to change an element within the list.

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> lst[0] 'a' >>> lst[2] 'c' >>> >>> lst[0] = 'aaaa' # Change an elem >>> lst ['aaaa', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> >>> >>> lst[9] Error:list index out of range >>>

List Mutable

The big difference from strings is that lists are mutable - lists can be changed. Elements can be added, removed, changed over time. We'll look at four list features.

1. List append()

# 1. make empty list, then call .append() on it >>> lst = [] >>> lst.append(1) >>> lst.append(2) >>> lst.append(3) >>> >>> lst [1, 2, 3] >>> len(lst) 3 >>> lst[0] 1 >>> lst[2] 3 >>> >>> # 2. Similar, using loop/range to call .append() >>> nums = [] >>> for i in range(6): ... nums.append(i * 10) ... >>> nums [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50] >>> len(nums) 6 >>> nums[5] 50

Common lst.append() Bug

The list.append() function modifies the existing list. It returns None. Therefore the following code pattern will not work, setting lst to None:

# NO does not work lst = [] lst = lst.append(1) lst = lst.append(2) # Correct form lst = [] lst.append(1) lst.append(2) # lst points to changed list

String vs. List .append()

Why do programmers write the incorrect form? Because the immutable string does use that pattern, and so you are kind of used to it:

# This works for string # x = change(x) pattern s = 'Hello' s = s.upper() s = s + '!' # s is now 'HELLO!'

Example: list_n()

> list_n()

list_n(n): Given non-negative int n, return a list of the form [0, 1, 2, ... n-1]. e.g. n=4 returns [0, 1, 2, 3] For n=0 return the empty list. Use for/i/range and append().

Solution

def list_n(n):

nums = []

for i in range(n):

nums.append(i)

return nums

2. List "in" / "not in" Tests

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> 'c' in lst True >>> 'x' in lst False >>> 'x' not in lst # preferred form to check not-in True >>> not 'x' in lst # equivalent form True

3. Foreach On List

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> for s in lst: ... # use s in here ... print(s) ... a b c d

Example: intersect(a, b)

intersect(a, b): Given two lists a and b. Construct and return a new list made of all the elements in a which are also in b.

This code is very similar to the string code.

4. list.index(target) - Find Index of Target

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> lst.index('c')

2

>>> lst.index('x')

ValueError: 'x' is not in list

>>> 'x' in lst

False

>>> 'c' in lst

True

Example: donut_index(foods)

donut_index(foods): Given "foods" list of food name strings. If 'donut' appears in the list return its int index. Otherwise return -1. No loops, use .index(). The solution is quite short.

Solution

def donut_index(foods):

if 'donut' in foods:

return foods.index('donut')

return -1

Optional: list_censor()

list_censor(n, censor): Given non-negative int n, and a list of "censored" int values, return a list of the form [1, 2, 3, .. n], except omit any numbers which are in the censor list. e.g. n=5 and censor=[1, 3] return [2, 4, 5]. For n=0 return the empty list.

Solution

def list_censor(n, censor):

nums = []

for i in range(n):

# Introduce "num" var since we use it twice

# Use "in" to check censor

num = i + 1

if num not in censor:

nums.append(num)

return nums

Style Note: Lists and the letter "s"

As your algorithms grow more complicated, with three or four variables running through your code, it can become difficult to keep straight in your mind which variable, say, is the number and which variable is the list of numbers. Many little bugs have the form of wrong-variable mixups like that.

Therefore, an excellent practice is to name your list variables ending with the letter "s", like "nums" above, or "urls" or "weights". Then when you have an append, or a loop, you can see the singular and plural variables next to each other, reassuring that you have it right.

url = (some crazy computation)

urls.append(url)

Or like this

for url in urls:

Constants in Python

STATES = ['CA, 'NY', 'NV', 'KY', 'OK']

ALPHABET Constant in HW4

# provided ALPHABET constant - list of the regular alphabet

# in lowercase. Refer to this simply as ALPHABET in your code.

# This list should not be modified.

ALPHABET = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z']

...

def foo():

for ch in ALPHABET: # this works

print(ch)

main() Function

You have called your code from the command line. The special function main() is the first function to run in a python program, and its job is looking at the command line arguments and figuring out what to do. With HW4, it's time for you to write your own main(). It's easier than you might think.

How Do Command Line Arguments Work?

How to write main() code?

For details see guide: Python main() (uses affirm example too)

affirm.zip Example/exercise of main() command line args. You can do it yourself here, or just watch the examples below to see the ideas.

First Run To See The Arg

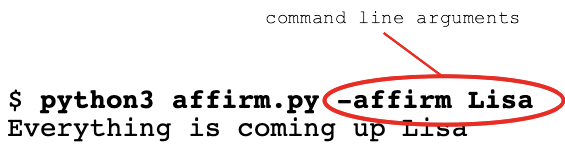

First run the code, see what the command line arguments (aka "args") do:

-affirm and -hello options (aka "flags")

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa Everything is coming up Lisa $ python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart Looking good Bart $ python3 affirm.py -affirm Maggie Today is the day for Maggie $ python3 affirm.py -hello Bob Hello Bob $

Command Line Option e.g. -affirm

The "args" To a Program

The command line arguments, or "args", are the extra words you type on the command line to tell the program what to do. The system is deceptively simple - the command line arguments are just the words after the program.py on the command line, separated from each other by spaces. So in this command line:

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

The words -affirm and Lisa are the 2 command line args.

args Python List

When a Python program starts running, typically the run begins in a special function named main(). This function can look at the command line arguments, and figure out what other functions to call.

In our main() code the variable args is set up as a Python list containing the command line args.

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

....

e.g. args = ['-affirm', 'Lisa']

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

....

e.g. args = ['-affirm', 'Bart']

Background: have print_affirm() etc. Functions to Call

For this example, say we have functions print_affirm(name) and print_hello(name) which are already written. The main() function will look at the args and call the appropriate functions. The key pattern is that main() can call functions, passing in the right data as their parameters.

Functions to call:

def print_affirm(name):

"""

Given name, print a random affirmation for that name.

"""

affirmation = random.choice(AFFIRMATIONS)

print(affirmation, name)

def print_hello(name):

"""

Given name, print 'Hello' with that name.

"""

print('Hello', name)

def print_n_copies(n, name):

"""

Given int n and name, print n copies of that name.

"""

for i in range(n):

# Print each copy of the name with space instead of \n after it.

print(name, end=' ')

# Print a single \n after the whole thing.

print()

How To Write main()

Exercise 1: Make -affirm Work

Make this command line work, editing the file affirm-exercise.py:

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -affirm Lisa

Solution code

def main():

args = sys.argv[1:]

....

....

# 1. Check for the -affirm arg pattern:

# python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

# e.g. args[0] is '-affirm' and args[1] is 'Bart'

if len(args) == 2 and args[0] == '-affirm':

print_affirm(args[1])

Exercise 2: Make -hello Work

Write if-logic in main() to looking for the following command line form, call print_hello(name), passing in correct string.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -hello Bart

Solution code

if len(args) == 2 and args[0] == '-hello':

print_hello(args[1])

Exercise 3 (optional): Make -n Work

In this case, the function to call is print_n_copies(n, name), where n is an int param, and name is the name to print. Note that the command line args are all strings.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -n 10000 Hermione