Note: If you were a member of a Macintosh user group in the mid-1980s, we'd like to hear from you. Please answer our questionnaire.

Apple Computer's history was linked to user groups from the company's beginnings. Both Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were in the Homebrew Computer Club, and the Apple I was unveiled at one of its meetings. User groups devoted to the Apple II were founded in the late 1970s, and many of them followed the development of the Macintosh closely; Macintosh user groups were founded immediately after the machine hit the market. (Drexel University's Mac user group was founded even before the computer was unveiled.)

The role of user groups in the early history of the Macintosh has never been examined, but it is worth looking at for several reasons. User groups served as distributors of software (at a time when the commercial software industry was still in its formative stages), news about Apple, and technical advice-- in short, an infrastructure supporting the Macintosh in its formative period.

Second, larger user groups also served as incubators of Macintosh enterprises. Software and hardware developers found user group meetings valuable sources of problems and feedback on inventions. They offered encouragement and connections to budding entrepreneurs, and provided training for future industry journalists and Macintosh writers.

Finally, user group newsletters provide an extensive records of their members' dealings with the Macintosh. Newsletters ranged from small, 4- or 8-page xeroxed fanzines to the Berkeley Macintosh User Group's 300-page leviathan. Their contents offer a sense of why people threw their lot in with the Macintosh, what they saw in the machine, and what uses they made of it: precisely the kind of source social historians can use to understand how users thought about computers.

Traditional histories of personal computing have focused on the engineers and inventors who created devices like the MITS Altair, Apple I and II, and Commodore Pet; a few user groups, most notably the Homebrew Computer Club, have cameos, but no one has made a systematic study of user groups. We know that in the 1970s and early 1980s they consisted largely of hobbyists and early adopters, often with substantial technical skills. Some also had previous experience with mainframe computers, and with user groups or special interest groups organized by professional societies.

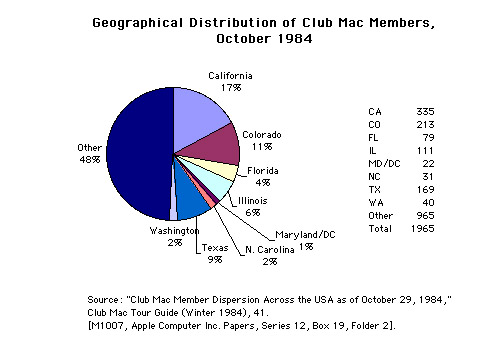

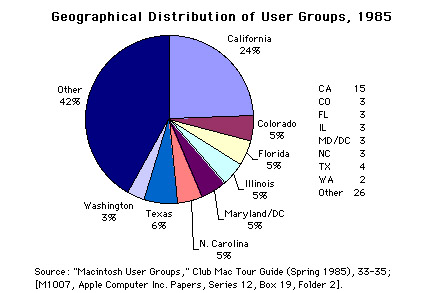

The first Macintosh user groups were founded shortly after the Macintosh was introduced in 1984; some Apple II user groups also added information about the Macintosh to their newsletters and meetings. Two surveys conducted in 1984 and 1985 by Club Mac, a Colorado-based user group, provide data on the geographical distribution of user groups and Macintosh users.

The first chart shows the geographical distribution of Club Mac members. Not surprisingly, many members are from the more populous and industrialized Plains or Western states.

A survey of the geographical distribution of user groups shows a more striking pattern. Fully a quarter of user groups were located in California; of those, the majority were located in the Bay Area, with Southern California hosting a number of the rest.

Arguably those Bay Area groups had the greatest opportunity to influence Apple and the Macintosh. Several user groups had been founded by early Apple employees: Bruce Tognazzini was a co-founder of San Francisco Apple CORE, and Andy Hertzfeld was co-founder of an Apple II user group in Berkeley. The most important Macintosh user group in the area, and arguably within the entire user group movement, was BMUG. Started in 1984 by Berkeley students Reese Jones, Raines Cohen, Tom Chavez, and others, BMUG's members went on to found numerous businesses, most notably the networking companies Farallon and Netopia; develop software and hardware for the Macintosh; write for Macintosh industry magazines; and serve as some of the machine's staunchest advocates.

All the user group-related primary documents are listed on a separate page. A good starting-point for exploring them is the Interview with Chris Espinosa. Espinosa was employee number 8 at Apple; his recollections of the Homebrew Computer Club, and perspective on the role of user groups in the early history of Apple, is quite valuable. Antecedents to user groups and early personal computing can also be found in the Interview with Reese Jones, one of the first members of BMUG, and later the founder of Farallon and Netopia. Bernard Aboba's Once More, With Feeling: The State of User Groups Today, BMUG Newsletter 4:2 (Summer/Fall 1988), is a perceptive analysis of how "things in the Macintosh World have changed a great deal since the beginning, and... User Groups must therefore change as well," written by a founding member of the Stanford Macintosh User Group (SMUG) and author of a book about online services.

Several pieces offer a view of the emotional ties user group members forged with their machines. Start with Ray Badowski's The Plan of St. Gall, The DeskTop Journal 10 (Winter 1986). Stephen Howard's The Cult of the Mac and the New, BMUG Newsletter 4:2 (Summer/Fall 1988), is a quirky, stimulating piece. Paul Danish, A Tribute to Apple's STAR Marketing, Club Mac News (November 1984), offers a view of the Macintosh philosophy in the context of a comparison of the Macintosh, Lisa, and Xerox Star.

The activities of BMUG are documented in several pieces. Ted Jones' The Ultimate BMUG Thursday Night... and You Are There, BMUG Newsletter 4:2 (Summer/Fall 1988), is an illuminating and often-hilarious account of an average BMUG meeting. Stephen Howard, An Introduction to BMUG, BMUG Newsletter 4:2 (Summer/Fall 1988), describes BMUG and its activities in 1988.

The philosophy underlying user groups is discussed in several articles. Scot Kamins' Introduction [to SF Apple Core], published in Ken Silverman, ed., The Best of Cider Press 1978-1979 (San Francisco Apple Core, 1979) places the founding of Apple Core in the context of radical activism. Ed Seidel, What a Users' Group Ought To Be, The DeskTop Journal 3 (Winter 1984), describes the impetus behind the founding of the Yale Macintosh Users Group. Raines Cohen and Stephen Howard, The State of the User Group, BMUG Newsletter (Fall/Winter 1987), and Reese Jones, BMUG After One Year, BMUG Newsletter (Fall 1985) reflect on the origins and aims of the largest of the Mac user groups.

User groups were publishers; Reese Jones' interview provides previously-unknown information about how the audiophile magazine The Absolute Sound influenced the BMUG Newsletter. Zig Zichterman and Carolyn Sagami's An Introduction to BMUG, BMUG Newsletter 4:2 (Summer/Fall 1988), describes what was involved in getting the behemoth out the door. User groups were early and enthusiastic adopters of laser printing and desktop publishing. Paul Danish, The LaserWriter: Stop the Presses, A Revolution is About to Explode!, Club Mac News (March 1985), waxes eloquent about the immense potential of desktop publishing. Norm Mayell, Notes on the Printed Letter and its Graphic Embellishment EBMUG Newsletter 7 (June 1985), is a more reserved survey of Macintosh printing. The anonymously-authored LaserWriter Users' Notes, SMUG Newsletter, 2:3 (August 1985), discusses the newly-released LaserWriter.