Fallon Segarra

Inside and Out

“You want to do what?” he asked, looking down. Even sitting, Dr. Martin Vidal, DVM, towered over me.

“I want to take radiographs and put them on top of photographs of horses in such a way that the outside and inside representations correlate.” I had driven two hours from Stanford University to UC Davis to request the diagnostic images that I needed.

“You do realize, of course, that doing this will limit your photography considerably. You’ll have to content yourself with the viewing angles we use to scan.” I hadn’t really thought too much about this, but now that it was being pointed out, I felt ridiculous. Here I am, showing a professor of radiology photographs from nontraditional perspectives, telling him I plan to slap on a radiograph that exactly matches.

“Of course,” I say. “I plan to shoot the photographs once I decide which scans to use. That way there’s no ambiguity.”

“Well, okay. Let’s go see Mathieu. I think he’ll be able to help considerably.”

~

Upon hearing what I was trying to accomplish, Dr. Mathieu Spriet, DVM immediately fished out a small brochure. On the cover was an oil painting of a greyhound. It was beautiful, but surreal – the artist had painted the different parts of the dog to correspond with how they would look through a diagnostic imaging tool. The legs, bent in mid-run, were painted as x-rays of legs; the head showed a CT scan of the brain. It was fascinating. I could not believe how detailed and accurate the painting was.

Dr. Vidal looked at the brochure, at me, then at Dr. Spriet. The three of us knew exactly what was ahead of me.

~

I have been around animals since before I was born. My mother rode horses until her sixth month of pregnancy, and continued to visit the barn during her last trimester. I am fondly told that “we” had a daily routine: get up, go visit Patch (the trusty steed), then head to the ice cream stand for a chocolate cone. We were so regular in fact, that the kid behind the counter would have the cone ready for her, and the stand’s other patrons got used to the pregnant lady cutting the line. Needless to say, when I came out of the womb at the end of that summer, I was a horse-and-chocolate-loving-Michelin-tire baby.

Growing up, I would play doctor with our teacup poodle, Killer, and run between the legs of the local horses (all forty of which I could identify by name before I turned three). My mother, a take-no-nonsense horsewoman, was my hero. The animals (myself included) would come in with cuts and scrapes. She would wash them, dry them, apply a special cream and a kiss, and they would heal. When I was diagnosed with an Atrial-Septum Defect, she scheduled the open-heart surgery, and told me that the doctor had to fix my booboo. I was afraid. My mother had always been able to fix my booboos. She told me to be brave. As I was rolled away to the operating room, I saw her usually calm and comforting face contort and twist with what I now know was anxiety as a single tear rolled down her cheek. I was three years old.

~

Years later, I realized that I wanted to fix animals like I remember my mom doing. She told me that I could, but that, unlike her, I would need to go to veterinary school. She explained that she wanted me to help them more than she could. Until the time I was thirteen, I did not truly know the difference between my mother and the veterinarian that came and looked at the animals and prescribed medication. Then one day my horse came in from the field with a puncture wound on his leg. The hole was only about the size of my thumb, but I could see all the way to the bone. When I showed my mom, she got pale and called the vet. She told me to stay with the horse and wait. She went up to the house. The doctor came and flushed the wound. She showed me (using a pair of sterilized scissors) how far up the leg the wound went and how to anesthetize the area before stitching. It was the coolest thing I had ever seen. When I went back to the house to tell my mom, I found her violently retching in the bathroom.

I decided to go to vet school.

~

With that decision came four years of intense academic work to keep good grades in a high school that held its 94%-is-an-A standard like a small child clutches an ice cream cone. All that work was validated when I got those acceptance letters from schools like Stanford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cornell University.

I chose Stanford because of the students I met at Admit Weekend. They seemed happy – something that my home life had prevented me from being for a while; they seemed to talk openly with one another – something that was frowned upon in my house; and they were genuine – something I had not seen in a long time.

So, here I am. When I go home to visit, my mother never stops talking about how much happier I am. The truth is I am more stressed than I was in high school and I am working harder than I have ever had to. I just seem happy – like many other Stanford students.

~

Last year, a friend organized D.A.D. – Duck Awareness Day. The main goal was to spread awareness about Floating Duck Syndrome, an unfortunate malady that Stanford students suffer from where one appears to be calm and composed on the surface but is actually paddling frantically to stay afloat. It is usually caused by the pressures of academic work, extracurricular activities, and family problems coupled with the taboos of discussing the issues. Before she had mentioned it, I had never heard about it. Upon listening to her description, I laughed. That little paddling duck was me. I was relieved that I was not the only one, but I was also upset that no one talked about it. It got me thinking about my mother’s horse, Beep, and how a single nuclear scintigraphy scan revealed a broken neck that he had never shown symptoms for.

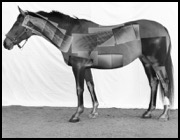

Then I thought that if I could make connections from my own stress to Beep’s, what would stop someone else from making the reverse connection? I started thinking about a photography project that would help me explore this. With the help of my professors, peers, SiCA, and VPUE I was able to produce the piece that now accompanies this essay.

~

Having competition horses and working for equine veterinarians has made me very familiar with diagnostic imaging. It made this project a little bit easier. For those readers without this advantage, here is a quick and dirty rundown.

With horses, there are five main types of diagnostic scanning: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), X-ray Computed Tomography (CT or CAT Scanning), Ultrasound, Nuclear Scintigraphy, and Radiography (X-rays). More information can be found below:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): This is a noninvasive diagnostic technique that produces three-dimensions computerized images of internal body tissues and is based on nuclear magnetic resonance of atoms within the body induced by the application of radio waves (1). (For a really good explanation of this concept, please visit Wikipedia… there is not enough space for me to attempt to explain physics here.) Typical equine uses are the same as those for an Ultrasound. MRI is used most commonly in hoofs, where ultrasound technology cannot easily penetrate.

X-ray Computed Tomography (CT or CAT Scanning): This is simply radiography in which a three-dimensional image of a body structure is constructed by computer from a series of plane cross-sectional images made along an axis (2). This allows veterinarians to visualize boney structures in three-dimensions to determine exact abnormalities.

Ultrasound: This is an imaging technique using sound waves with frequencies above the audible range of human hearing to two-dimensionally visualize subcutaneous body structures. Typical equine uses are fetal development monitoring during pregnancy and diagnosing pathology or legions in tendons, muscles, nerves, ligaments, soft tissue masses, and bone surfaces.

Nuclear Scintigraphy: This is a noninvasive imaging technique performed by administering radionuclides (radioactive elements called isotopes or tracers) tagged to drugs that travel to a specific organ in the body. The radionuclides emit gamma radiation that is imaged with a specialized “gamma camera”. The location and amount of the radionuclide within the organ help assess the function of the organ. After scintigraphy, the patient is isolated for 12-24 hours to allow the body time to clear the radioactive tracer (3).

The mechanism by which this works is that the tracer is administered intravenously and images are taken at various times. The interpretation on the images is based on the principle that healthy bones incorporate certain bone tracers into their structure. Healthy bones are dynamic. The distribution of tracers in bones depends on the rate of this bone turnover and blood flow. The bone scan reveals the changes in the metabolism of the bone more than actual changes in the bone structure. The changes in scintigraphy usually precede the changes noted on the x-rays, since the bone's metabolism usually changes before the bone's structure changes (2).

Typical uses include evaluation of bone, brain, kidneys, thyroid, liver, and other soft tissue functions. Most commonly used in horses for bone scanning in patients with poorly localized lameness when x-rays are inconclusive. Small lesions can result in significant changes in the metabolism of the bone that are assessed through the images. Bone scans are useful for diagnosing infections, tumors, and arthritis.

Radiographs: The images that are formed by passing an X-ray beam through some section of a patient’s body are recorded either on film or some form of digital media. Generally, the images recorded on film are viewed as transparencies on a lighted view-box or illuminator and the digital images are viewed on computer displays (4).

The typical uses include visualizing the boney structure of an animal to determine abnormalities such as broken bones and the presence of foreign objects.

~

Deciding to use radiographs and nuclear scintigraphy scans in the final piece was not a decision I made. It was forced on me. Thanks to Drs. Vidal and Spriet, I had access to millions of images. MR images, CT scans, radiographs, nuclear scinitgraphy scans, and ultrasounds were at my disposal. Unfortunately, the nature of MR images, CT scans, and ultrasounds is such that they show cross-sectional areas of anatomical structures, not full-side views.

Being limited to radiographs and nuclear scintigraphy scans turned out to be a blessing. It allowed me to really see how the equine skeletal structure deals with stress and how these diagnostic tools allowed those stresses to be identified. A seemingly normal right front leg was radiographed. The scan showed thickening of the splint bone and a fungi-like growth on the fetlock. That thickening was then interpreted as a healed splint fracture, and the growth as the beginnings of ringbone. An x-ray of a healthy horse’s abdomen revealed a bowling ball sized enterolith that needed to be removed surgically before it became an impaction in the intestine. The line of demarcation between the inside of the horse (what he feels) and the outside (what he shows), fuzzy as it is, was set in my mind. It was this ‘line’ that ultimately led me to the conclusion that it would be best to keep the anomalies of the diagnostic scans in the final piece.

~

When you look at another being, what do you think about? Chances are the surface dominates your thoughts. When we see the surface of something familiar, we often forget the complexities that exist within. We forget that hopes, dreams, anxieties flood other living beings. We forget about the bones, the tissues, the living breathing cells. We forget the effort that ducks put into floating serenely across the lake.

How does this general unawareness affect our perception of the world and ourselves? Where does the life go when we talk about another’s clear skin or short skirt? If we are not aware of it, does it even exist?

In closing, I would like to ask you a favor. The next time you talk to someone you care about ask them how they are. I don’t mean have the how-are-you-fine conversation that has come to dominate our fast-paced society. I’m asking you to sit down with them. Grab a coffee/tea/soda/water and really find out what’s going on in their life. It might mean opening yourself up to topics that make you uncomfortable, watching someone cry, lending them a tissue/shoulder/hug. See if either of you can discern the place of separation between the surface appearance and the internal occurrence. Maybe you can find it. Maybe you can explain to me why it exists. Maybe then, together, we can figure out a way to close the divide.

References:

1 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/magnetic+resonance+imaging?show=0&t=1303275831

2 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/computed+tomography

3 http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=0+1302+1473&aid=1007

4 http://rpop.iaea.org/RPOP/RPoP/Content/InformationFor/HealthProfessionals/1_Radiology/Radiography.htm