Catherine Le

Trust in Creativity

Creativity comes from trust. Trust your instincts. And never hope more than you work. -Rita Mae Brown

“So…What exactly are you doing again?”

“I am drawing the tissue and cellular levels of rheumatoid arthritis and overlaying the image with quotes from my interviews with people living with the disease.”

The response was always positive, but I always spotted a hint of confusion. I don’t think anyone could really picture what the final project would look like in their mind. I didn’t blame them since I couldn’t do it myself for the longest time. In fact, I was glad that they never asked a follow-up question about how I planned on executing this idea of mine. It was one thing to have a concept, but a completely other beast to know how to carry it out. I knew the components that were required for my project. One, I needed to get interviews with people living with rheumatoid arthritis. Two, I needed to come up with an original visual representation of the disease. But what to do from there, I will admit that I did not know. How do I force these two things together to form one unified object? I will relieve the suspense and say that in the end I did find a solution, but there was no real worry. With the creative process, you learn eventually to live comfortably within the unknown. You lean on your instincts and the advice of others to eventually direct you down unexpected paths. I needed to trust that my journey that started with an idea would end somewhere wonderful. This paper is a recollection of my journey bringing an abstract concept in the mind to physical reality.

In the beginning was the Word. -Genesis

You never know what to really expect when you meet someone for the first time. Will they be friendly? Would they have just come from a bad day and only answer in terse responses that sound more like curses? I was waiting for the clock to hit 10 AM, my appointment time to meet Susan Dorey. Through my online exploration, I found her website Living with Rheumatoid Arthritis, a one-stop resource site and blog, and immediately contacted her. She responded warmly to my relief.

I glanced over the list of questions that I had tailored to her based on the information that I could glean from her website. Originally, the list had been much longer but was shortened after I spoke with Dr. Kate Lorig, a Stanford professor of medicine in the Department of Immunology and Rheumatology and director of the Stanford Patient Education Research Center. Dr. Lorig had long been in the business of asking the right questions at the right time. As a researcher, she had years of experience with interviewing patients on chronic diseases. During a consultation meeting, she had taken a quick glance over the list.

“Too long. It’s too long. You need to shorten it. First, you’ll never get through all these questions. Second, interviews go in directions that you never expect, so you want to prepare room for that by allowing for spontaneous questions. Ask the questions that you definitely need, and go from there” (1).

She, of course, was right. Interviews sometimes are like organic creatures to me. They require a seed, soil, and water, but then they always seem to grow in whatever manner they pleased.

When my alarm clock went off, I turned on my Skype and found Susan’s username online. I sent her a video chat request and waited nervously. The video came on after a few minutes of static and delay, and I was in front of a woman, sitting comfortably on a couch in gym clothes. Susan was a bubbling fountain of youth. It was hard to imagine that she had survived two sons and a battle with rheumatoid arthritis.

She told me, “I can do everything that I used to do. I am 52 years old, and I would challenge a 40-year-old to keep up with me” (2).

And I believed her.

Even with our allotted time of one hour, we didn’t get through half of my questions. Susan had so much to tell me about her kids, her hobbies, and her life after her diagnosis, and I always got too distracted by the conversation to remember to ask the next question. As far as first interviews went, it was wonderful. I felt energized and excited to be learning so much. My head was swimming with all the possible quotes that I could use for the art project.

After my conversation with Susan, I immediately got on the phone with Angela Lunda. I was fortunate enough to be able to get back-to-back appointments. Angela ran a blog called Inflamed: Living with Rheumatoid Arthritis. An avid traveler and photographer, Angela had amazing photos of her trips, but she also had these stunning shoots of simple things that she ran across in everyday life on her blog. I saw in one of her recent posts that she had also taken pictures for the Arthritis.

My experience with Angela was completely different. Still in her early thirties, Angela was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis during college.

“You’re going to college. You’re going to school. You’re hanging out with all these people. They’re really active and doing all these things. And you can barely get your papers done on time because your hand is swollen or hurts” (3).

It was clear that untreated rheumatoid arthritis is a debilitating, painful, and isolating the disease. Though Susan had called the disease “almost death,” her bubbly personality and rare and complete recovery had masked the true effects of rheumatoid arthritis from me. Angela however was still dealing with isolation and sense of loss and felt comfortable enough to show me, and it was difficult for me to hear her story without being emotional affected. When we hung up, I was drained from sympathizing and exhausted from giving her my acute attention.

This became the normal pattern of each interview. I would listen, empathize, and feel worn out at the end. Also an unexpected and large feeling of gratitude welled up inside me. These people were letting me into their lives and sharing a part of them that they rarely share with even those around them.

In the end, I was fortunate enough to speak to eight incredible people. I found them either through brute force Google searches or Dr. Lorig, who was willing to pass my project idea along to her friends. Each person was different, and their ages varied widely. There was Ian McNeil, who lived in Scotland and had been diagnosed while he was finishing his term with the British Royal Air Force. There was Nikki Martin, a friend of Angela’s who wanted to participate in the project. There was Sarah Nash who has an online blog Single Gal’s Guide to RA. There was also Kelly Young who ran a site called RA Warrior. Both women were celebrities in the online community for people living with rheumatoid arthritis and had been featured in various health articles.

Yet, despite their differences, there were some commonalities with their experiences of rheumatoid arthritis that threaded them together. They all spoke about feelings of loss and pain, the importance of having a strong relationship with their physicians, and common miscommunications and misconceptions about rheumatoid arthritis. Yet, for the most part, they had learned to live successfully with a disease that is unpredictable in nature. A person living with rheumatoid arthritis could wake up one day and find himself robbed of all energy and mobility. They were highly educated people, who knew to be wary of new drugs that could harm more than help. Most had a strong understanding of the disease, and some were ready to teach me the latest scientific news and studies on drug treatment. One of my wise interviewees, Gail Riggs, explained it to me clearly.

“When you have a chronic illness, it’s going to last the rest of your life. If you’re going to live with something the rest of your life, what’s the first thing you want to know? The first thing you need to learn is everything about it” (4).

Though Gail had hit and passed her sixtieth birthday a few years ago, she was still actively writing grants, doing research, and teaching as an educator in the Arizona Arthritis Center. Gail had juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Because of that arthritis is often misunderstood as a disease of the aged, she was misdiagnosed several times as a child. This was also true of Mary George who went through four physicians before being properly diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. During that time, her cervical spine had fused on her neck, but this has not really stopped her in any way. She now runs a non-profit, Top Dog, in Arizona. Top Dog helps people with disabilities train their own aid dog.

When I had finished the eight interviews, I was relieved to no longer have to recover from emotional intense conversations. I transcribed the recorded interviews. Because I felt a sense of indebtedness, I wanted to be transparent with intentions and sent them each their transcript of the conversation. Along with the transcript, I sent a survey with my four general true statements that I believed applied to people living with rheumatoid arthritis. I asked them to rank the following:

1) Having uncontrolled RA can be characterized as a sense of lost in movement and of pain.

2) If you do not have RA, it is difficult to understand RA. It is difficult to explain what it means to have RA. Yet, communication is important.

3) A successful relationship with a physician is crucial, and this relationship should be a partnership where both are educated on the issue from all aspects.

4) You must make RA live with you and not you live with it.

On a scale of one to five with five being the most correct for their situation, all the statements received either a four or five. In some ways this was reassuring that I had understood my experience interviewing them. As an outsider, I was never sure if my impressions were correct. These four statements became the categories by which I could sort the quotations. I took up apart the transcripts and placed the quotes into four categories: Life after Diagnosis, Miscommunication, Relationship with Medicine, and Final Words of Wisdom.

I was a third of the way done with my journey.

Traveling is a brutality. It forces you to trust strangers and to lose sight of all that familiar comfort of home and friends. -Cesare Pavese

It is always nerve-wracking for me to show drafts of my work. It was especially terrifying to share my designs of the cellular and tissue levels of rheumatoid arthritis since for the most part the visuals came from my imagination. There is always a tiny man, screaming in my head. It’s not ready! It’s not ready!

I was driving by a row of houses in Menlo Park on a Saturday morning and feeling the butterflies beating their wings against my stomach lining. Dr. Andrew Chan had invited me to his home for our second official consultation meeting. I had met with him once back in December in his office in Genentech. Back then, I had not begun to draft prototypes of my final work, so we spent most of our session learning the known facts of rheumatoid arthritis. Since he had once held a position as a professor at a university, he easily slipped back into his role as a teacher. He used all the whiteboard markers at his disposal to draw diagrams and explain to me the current state of research. I learned that for the most part scientists still have no good mechanism or cause behind rheumatoid arthritis.

His home in Menlo Park was clean and neat. I was introduced to his wife and offered a chair at his dining table. His daughter passed by with some books in her hand. I felt strange that he would have allowed me to enter such a private sphere. After I had settled down on my seat, I took out my panels and displayed the drafts to him.

There were four panels in total. My original plan was to focus the drug Rituxan and its mechanism of inhibiting the self-perpetuating cycle of rheumatoid arthritis. An autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis causes the infiltration of white blood cells into the synovial tissue of the synovial joints, which are the most movable joint in the whole body. People afflicted with the disease usually have inflammation in the hands and knees, though symptoms can appear throughout the body. The recruitment of white blood cells in fact causes more recruitment in a forward feedback loop. This causes the synovial tissue to grow, forming a mass called the pannus. The cells in the pannus include B cells, T cells, macrophages, and fibroblast cells (5). They are accompanied also by angiogenesis, the growth of blood vessels. The white cells release cytokines that activate bone destruction and cartilage erosion, while general inflammation causes swelling, stiffness, and immobility of the joint. Worst of all, rheumatoid arthritis causes immense pain and fatigue. Where Rituxan comes in is its ability to affect B cells. Rituxan is a monoclonal antibody that tags the CD20 receptors of B cells, causing their destruction through apoptosis, complement-dependent cytotoxicity, or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (6).

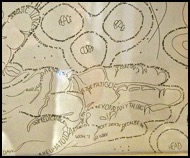

Yet, I was no longer sure if I was interested in the mechanism of Rituxan any longer. Also, since no mechanism or cause for rheumatoid arthritis is known, my drafts mainly focused on depicting on the interface where the pannus meets the cartilage or bone. This was what I found visually exciting. In the first panel, I drew an enlarged image of an open hand and a joint. My goal was to show a gradual magnification into the joint, and the panels would take viewers deeper and deeper into the pannus. The second panel was a zoomed-in visual representation of the destruction of the cartilage by the growth of the synovial tissue. I had drafted the second panel based on photographs of tissue stains of synovial tissue that I had obtained from Dr. Mark Genovese of the Rheumatology and Immunology Clinic at Stanford. The third panel showed a close-up of the cells and some blood vessels. I had reserved the last panel to draw the mechanism of Rituxan but was not inspired to draw anything more than a circle to represent the B cells and some monoclonal antibodies for Rituxan.

Though Dr. Genovese had also examined by panels and found no need for them to be changed, I still felt the prickly nervousness as Dr. Chan continued to examine the drafts. With a smile, he quickly rattled off some criticisms. I noted them on my computer. What I found was that the blood vessels needed to be more prominent. Angiogenesis is extremely volatile in the pannus. The second main criticism was that the cells in the third panel were too ordered and were more of a disordered mélange. When we arrived to the last panel, I perked up my ears and listened.

“It doesn’t seem that your artwork needs to focus on Rituxan in particular. It’s interesting enough that you want to use quotes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rituxan would just confuse and distract your main message” (7).

I found myself agreeing with him. I had not felt drawn to the idea of drawing the mechanism of Rituxan after doing some research but for some reason had felt committed to the idea simply because it was the original plan. It was liberating to let go of it. Instead, I decided to draw molecular representations of common drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in the last panel. Drugs and medications always came up during my interviews and still held an important role in the lives of people living with rheumatoid arthritis, but it was no longer necessary to highlight a specific drug. In the end, I rejected some of Dr. Chan’s feedback but did make some dramatic changes to the third panel, where I made a large blood vessel the main focus.

It’s always important to ask for directions when you’re exploring a foreign land, but I try not to forget to use my own internal compass. I was two-thirds of the way done with my journey.

One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things. – Henry Miller

Now, it was time for the moment of truth. It was time to execute my concept of placing the words and the visual art together. I fortunately had some advice in how to tackle the problem. Kenney Mencher, my creative art mentor, gave me several techniques on how to work through my creative block. His motto was to approach the problem from several angles. He made several copies of my drafts and commanded that I do anything to them. So, I did.

I made big words, small words, and words of different fonts. I oriented them every way possible onto the drafts without fear of causing irreparable damage since these were only copies. I had lines running one direction. One sentence repeated itself over and over again in crooked lines. Most of these attempts were to be honest failures. They looked awful and sometimes obscured what the original image even looked liked. It was easy to overwhelm the visuals of the biology with the words. Yet, for every failure, I was a step closer to finding a style that would fit could work. Eventually, I decided that small, uniform block letters would be the final font. To prevent the words from covering up the original image, I decided that the quotations would only follow the drawn lines. Simplicity was the key. This, however, was only half the battle. I still had not solved how each individual quotation would fit on the drafts.

What was decided beforehand was that each panel would represent one of the general statements that I surveyed after the interviews. The first panel was for quotes about how life was altered by rheumatoid arthritis and the general sense of loss that accompanied it. The second panel held stories about misunderstandings and communication. The third panel held stories about the speakers’ relationships with medicine and physicians. The last panel held any quotes that truly allowed their personalities to shine through the paper and how they were able to overcome the disease.

With my transcripts in one hand and a pencil in the other, I began to match the quotes with the corresponding image. I learned pretty quickly that several factors had to be considered in the decision. I learned quickly because the first few placements did not work out as planned. For each quotation, I asked myself a series of questions. One, how long is the quote? Two, what is the quote about? Three, should this quote be in a prime location for someone to spot it? Four, are there any words in the quote that is worth repeating or enlarging to emphasize their importance? Even then, I wrestled with each placement. Here? No. There. No. No. It was better back in the first location. With time, I learned to estimate what length would fit where. Though I wish I could say the process became automatic, it never felt easy. It did however become more natural in the sense that I learned to listen to my instincts. When something felt right or wrong, I could tell by a gut feeling. I don’t really know how to explain it. Certain quotes felt a home in certain locations but jarring in others. Also, I found myself making symbolic decisions. For instance, Ian had one quote that really struck out to me.

“I certainly don’t talk about it with friends, other members of the family, or the children. I tend to keep my feelings about to myself or share it with my wife. Not any wider than that” (8).

This emotion of isolation that he felt was common for many of people that I spoke to, so I decided to repeat this quotation multiple times. I chose single chondrocyte cells of the cartilage in the second panel to be their location because these single chondrocyte cells lived in isolation in the matrix. In this way, the image could represent what the words were stating.

In a similar fashion, I placed certain quotes that showed supportive relationships onto the osteons of the compact bone. Bones because of their natural function seemed well suited to be the location for these quotations. Mary George’s relationship with her husband is an example.

“My husband… would puts [my hair] in a ponytail during the summer when it’s hot. He’ll put in my earrings for me. I can’t reach my feet so he cuts my toenails” (9).

I transformed certain nuclei into words because these words represented the theme of the quote that formed the membrane of that cell. The nucleus is central to the cell just as the chosen words were central to the speaker. For instance, I used the words “Peace Corps” for the nuclei for one of Angela’s quote.

“What surprised me was that in my application I wrote about my experience in Ireland and in France and also doing that while having RA, so I thought and hoped that yes I would be able to do the Peace Corps. But then again I wasn’t surprised…They have a list of conditions that cause them not to take people, and rheumatoid arthritis was on that list” (10).

I also chose special places for some quotes that I felt were the most important to share. The quotes that lined the synovial tissue of the joint in the first panel for instance were the most important quotes of that panel for me. Also, since last panel had the largest amount of empty space of the four panels, each quote placed there would be easily highlighted. The last panel therefore had some of my favorite quotes about how to live life victoriously.

“I know that this is temporary. Our life is just temporary. For eternity, I won’t have any more tears or pain. That’s something to look for in the future” (11).

“It’s like you’re traveling along at normal speed dealing with life then suddenly the brakes are slammed on and you have no idea why that’s happened” (12).

In art, if you don’t know what to do then just try and keep trying until something works. I found this to be true throughout this process. By trusting my instincts, I had achieved a certain balance between the drawn lines and the words. My goal was to have them live in harmony and not allow either part to overwhelm the other. Through this process, I was forced to understand myself. It was only when I comprehended what I found to be important from the interviews that I could listen to my instincts.

It was unexpected how much self-reflection was required of me to finish this last third of my journey.

Not all those who wander are lost. – J. R. R. Tolkien

“Collisions” is the final culmination of year-long process in The Senior Reflection program and my desire to meld together science and humanity. It was only made possible through the great support of the people in The Senior Reflection and others who believed in my idea enough to let it grow. In simple terms, it is a four-panel, inked artwork that depicts the tissue and cellular levels of rheumatoid arthritis overlaid with quotations taken from eight interviews with people currently living with the disease. It was titled “Collisions” because I saw many conflicts that surrounded the subject of living with rheumatoid arthritis and in my own process of creativity. The day-to-day reality of living with rheumatoid arthritis is in conflict with a person’s desire to lead a fulfilling life, while words and visuals appeared to be at odds for me in the project. But “Collisions” is in fact much more to me. It is a long, winding journey that begins with trust and is fulfilled by trust. It is about trusting my own instincts, trusting others, and trusting that the journey only promises great things in the horizon.

References

1. Lorig, Kate. Personal Interview. 4 March 2011.

2. Dorey, Susan. Personal Interview. 4 April 2011.

3. Lunda, Angela. Personal Interview. 4 March 2011.

4. Riggs, Gail. Personal Interview. 7 April 2011.

5. Haynes, Barton F. "Pathology." In Rheumatoid Arthritis, by Barton F. Haynes, David S. Pisetsky and E William St. Clair, 118-133. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004: 124.

6. Teng, YKO, TWJ Huizinga, and JM van Laar. "Targeted therapies in rheumatoid arthritis: Focus on rituximab." Biologics: Targets & Therapy, 2007: 327.

7. Chan, Andrew. Personal Interview. 1 March 2011.

8. McNeil, Ian. Personal Interview. 12 April 2011.

9. George, Mary. Personal Interview. 7 April 2011.

10. Lunda, Angela. Personal Interview. 4 March 2011.

11. George, Mary. Personal Interview. 7 April 2011.

12.McNeil, Ian. Personal Interview. 12 April 2011.