Natalie Durant

Flowing Through Tradition

Reflecting on Crisis

“Life is a race between education and catastrophe”

Why? My father has asked me a couple of times the big question, “why?” His question is not very specific but I assume he is asking why I am spending my time working on an art project that on the surface may seem like a pointless endeavor. There were times, deep in winter quarter, when I asked myself the same question. I questioned the motivation behind my art project and if my time would have been better spent working on a solution to the water crisis. My project won’t help bring clean water to women in rural Africa, or raise awareness for the crisis like the campaigns of charity: water and water.org. So what was the point? Surprisingly the answer came through the rejection and subsequent re-submission of my grant proposal. Through this process I discovered that the driving force of my project was my own personal education, exploration and development rather than raising money for women in Africa.

I was surprised by how much I learnt about myself through this project and class. I discovered my tendency to overachieve and take on too many things at once. This invariably leads to failure. However, I do not regret it. I learnt more from challenging myself and failing, than I would have done had the project gone smoothly. My ‘safe’ option proposal was a painting. I have always enjoyed painting and was sure that through the Introduction to Painting course I would be able to complete my capstone without too much difficulty. It was extremely helpful at this point to have professors who challenged me to design a project using actual water. Creating a project with so many unknowns was intimidating. Partnering with experts across many disciplines helped me compensate for my lack of ceramic and engineering experience to pull together a dynamic final project.

Banny Banerjee, my official science mentor, told me that simplicity was one of the most important features of an artwork, and yet very difficult to achieve. This was intimidating advice as I was unsure how to turn a complex issue into a simple piece. The original fountain design was very complex with a number of different elements, all with their own significance. Light through water was one key focus I abandoned as soon as I tested it. I also dropped the goal of being able to view the entire water cycle, which represented the need for sustainable solutions in Africa. As I attempted to deal with the problems of my initial design, the fountain became simpler and the limitations and failures I encountered, ultimately brought simplicity to my final fountain. The flow of the water in the fountain dictated the focus of the piece. Although my project had begun with water at its core, by the end it was secondary to the pot and thus the female form.

My Crisis

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.”

― Winston Churchill

The weekly TSR workshops provided interesting snapshots into the successes, challenges and creative process of each student to reach the final exhibition. However, there was so much behind the scenes work that was not viewed. My time at the ceramics studio felt very personal and separated from my Stanford career. I was working in the studio during the last few months of my life-long career as a competitive swimmer, contemplating life after swimming and Stanford. The studio provided a perspective on a community outside of swimming and college that helped me through this transition period.

The pot began on a mould. I made perfect coils using an extruder that I wrapped around each section. Each coil had to be scratched with a needle tool (‘scoring’) and the two coils worked together to form the smooth surface.

Adding 2-3 layers of coils took me roughly 3 hours. I was always worried about the top section drying out between sessions. Although I had a rough idea of my final goal, I felt as though the clay was controlling the shape and thus the size of the pot.

The pot reached this size after about 2 months of work. At this point I could barely lift it on my own and used a wheelie stool to move it across the studio. It was at this stage that we realized the pot was lopsided and, due to the weight of the wet clay, part of the side had collapsed in on itself.

Many solutions were discussed trying to salvage the hours spent molding and building the vessel. Finally the owner of the studio, Dan, suggested that he throw a pot in three sections and recycle the vessel I had lovingly hand built. Dan based the pot on my design and directions and I was there throughout the process – his “sous-chef.”

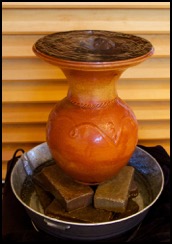

The twenty-minute drive down to the studio to pick up my final ceramic piece was a memorable and reflective car ride. I was extremely nervous; worried I would hate the color or that the pot had broken. I felt a sense of finality, as it would be the last time I went to the studio. I remember seeing the pot sitting on this wheel, serenely, as though it had been waiting for me. I knew in that instant it was exactly what I had imagined.

Installing the fountain in Wallenberg hall brought new challenges and problems I had not anticipated. The water splashed and spilled out of the base making the floor wet. A trip to Jo Ann’s for fabric and many towels kept the floor and table dry. In addition yet another trip to Home Depot was required to purchase a surge protector and ensure my fountain was safe for display.

Flowing Through Tradition had finally made it.

•••

I started my project with the ceramic pot by enrolling in an introductory wheel throwing class at the Higher Fire Studio in San Jose. Ten minutes into the first class I realized three things: a) wheel throwing is very difficult b) I had severely overestimated how long it would take me to throw a pot the size I was aiming for c) how easy expert potters made it look. I was struck with the realization many people probably felt the same way when they watched me swim. I left the first class deflated, searching for an answer to produce a large enough pot to be the center of a fountain. My answer was hand building, a method that required very different skills and a lot of patience. When building by hand, the clay has to be molded into coils, either by hand rolling or using an extruder. The identical, smooth coils that literally oozed out of the extruder appealed to my perfectionist nature. The coils were laid on top of each other and “scored” using a metal needle tool. Scoring was a monotonous and seemingly never-ending task. However it was followed by my favorite part in the pot building process - smushing the two coils together and wriggling them side-to-side to force a secure bond. The joining process was messy as it required slip (very watery clay) but I enjoyed the process of forcing two separate coils into one. Smoothing the walls, both inside and out, was the final step in this process.

An expert potter can throw a large ceramic piece in less than an hour. By comparison, hand building a vessel of the same size takes weeks and the method forced me to spend many hours in the studio in winter quarter. Although it was time consuming, hand building the pot made me feel more connected to the traditional African pot making process. It gave me time to contemplate the issues facing women in Africa and reflect on my own personal problems and adjustments that approached with the end of my swimming career. One week after my final swim at the PAC-12 Championships, I wrote in my journal that I had three major worries. The first concerned my body image and physical changes that would undoubtedly follow retirement and no longer working out twenty hours a week. The second was that “I would forget.” Forget the meet, the races or team camaradery. I am sure that in time some of the details will fade, but the sense of accomplishment I felt at the end of PAC-12s will stay with me forever. My third worry was that my pot was going to break or fail. A few days after my entry I went into the studio to discovered that my pot had collapsed in on itself. After some consultation with various teachers in the studio I made the decision to walk away from the piece I had been building. Abandoning the time and effort that had gone into the ceramic piece was a heart wrenching decision but looking back it was definitely the right choice. During the last few weeks of building I was becoming increasingly nervous about how long the vessel would take to dry and concerned with the weight of the final piece. My over-ambitious design for such a large ceramic vessel led to the failure of the piece, however this was one of the biggest lesson I learnt during this project.

Initially I was very disappointed that I had not thrown the vessel myself, and felt the need to correct people when they asked if I had made the pot. But Terry Berlier’s talk helped me to realize that artists always collaborate and that alliances may be one of the most important aspects of artwork. Whether it is helping to design, build or edit a work, art is a collaboration. The community at the Higher Fire Studios reflected the nurturing and supportive nature of art and my time spent in the studio gave me a new respect for potters. I feel as though the term ‘pottery’ does not reflect the work that is envisioned, created and accomplished by the artists in the Higher Fire Studios. After a few weeks working among the members on the hand building tables in the studio, I felt as though I belonged to this supportive community. The inclusive, interested and supportive culture among the group of eclectic members was a major reason why I was able to turn my vision into reality.

Flowing Through Tradition

“Art in Africa is not a commercial enterprise but a part of life itself”

Sitting below the stairs, encased in the alcove, I sit and watch. Watch the students rush past, barely glancing this way, their heads down, fingers moving fast. Hurrying. Yet how peaceful I stand. The water caresses my body, finding groves in the rough clay, the mark of my imperfections. The cool, calm water lifted up inside of me, gravity pulling droplets back down. Trickling through the cracks in my center. Gurgling as it falls back to join the pool waiting below. The rest is forced upwards, inside of my dark neck, towards the light. Billowing out from the center, each droplet yields to the power of the current moving it steadily closer to the edge. The molecules dip and curve until gravity wins once again and they fall. Tumbling as a sheen broken only by the decorative scarring that mark my shoulder. Some droplets attempt freedom. They ricochet away from my curved body into the blackness beyond. Occasionally someone stops to watch, mesmerized for a minute by the droplets dancing in the light. But they are gone and the darkness grows deeper. So I sit, wondering when the cycle will end. The droplets gone. The reservoir dry, and my body aching to feel the cool caress once more.

•••

I based my initial design for the vessel on a traditional African pot I saw in the Cantor Art Museum. Although I was not totally set on a particular shape, I did have an idea of the feeling and message I wanted the ceramic to portray. Strong, feminine and earthy. The final shape is narrower than I had envisioned and the neck more dominating providing strength. The smooth curves and round belly add to the feminine qualities. Finally, the color is intricate and varied; warm yet powerful and enduring, correlated to the daily, ingrained struggles of the African women. During my last season on the swim team, our coach, Greg, asked the team to each choose two words. The first was what we brought to the team and the second was what the team gave to us. My words were resilience and strength. Working through three broken bones last year and swimming slower than I had done as a 14 year old, I definitely felt that I had developed a resilient attitude and hoped to maintain that through the final season. I also believed that my strength to continue and maintain a positive attitude in the face of adversity came from the team around me. In my last few months Greg told me to live in every moment and enjoy the experience of being surrounded by a group of women, all working towards the same goal. The strength and resilience that helped me make it through my last year of swimming flowed into other aspects of life. The failure in the ceramics studio and other challenges in the project led to an enormous sense of accomplishment (and relief!), that I would not have experienced had the project gone smoothly. My final swim meet at the PAC-12 Championships was similar. I swam faster than I had done all year and although I did not swim personal best times in every event, I felt a sense of achievement and pride. It was the perfect ending to my life-long swimming career.

My last, and most daunting task of the entire project, was writing the title for my finished piece. I felt as though an entire years work would be reflected in the few words that I chose to introduce my artwork to the Stanford community. I wanted the title to reflect the calm and peaceful nature of the fountain. The title I eventually came to, Flowing Through Tradition, encapsulates a number of themes that I wanted to portray in my fountain. Superficially, the water literally flows through a traditional African vessel. The title refers to the traditional values of the women walking to collect water and the gender roles that are engrained into African society. Women are burdened with the task of collecting water for their families and have been for hundreds of years. In a more metaphorical sense I feel as though I have been flowing through tradition during my four years on the swim team at Stanford. I have grown to understand and love the impressive, and sometimes intimidating, history and traditions of swimming at this great University.

I found other aspects of the presentation of my fountain my easier than the title. During the design process I imagined my fountain being accompanied by a leaflet or information postcard on the water crisis. However, I chose to include only details in the accompanying blurb for the viewer if they chose to read it. I hope the audience understands the traditions the pot is based on and how the piece is connected to water and women in Africa. I used the facts that initially drew me to this topic to shock the audience and make them aware of the crisis in developing nations. For example, 2.5 billion people worldwide do not have access to sanitized water and women spend three hours a day walking to collect water. As I found in my research, there are more questions about how to solve this problem than answers. I hoped to make the audience think about the issue rather than illicit an action. Research into the crisis revealed the complexities of the issue and I realized that digging wells in rural villages is not enough to solve the problem. Instead, understanding the needs, culture and history of women in Africa is paramount if solutions to the water crisis are to be found and implemented.

Complexities Uncovered

"If you don't like something change it; if you can't change it, change the way you think about it"

- Mary Engelbreit

My initial research into the water crisis mostly involved websites of big corporations such as charity: water, Blue Planet Network and the World Health Organization (WHO). As the project developed I reached out to experts at Stanford who are conducting research on the topic. Banny Banerjee, a Design School Professor, started the platform, Change Labs, that aims to create social change through collaborations across fields of expertise. Kory Russel, a Ph.D. student in Environmental and Civil Engineering does research on the caloric output of women carrying water in Mozambique. In my meetings with Professor Banerjee and Mr. Russel, both highlighted the complexity of the crisis and the challenges that face implementation of solutions in developing nations. Digging wells in rural villagers seems to be the favorite solution for many corporations. Although many NGOs publicize the need to provide sustainable solutions, often the local culture is ignored, and wells are left unused. For example, imagine charity: water spend hundred of dollars digging a well in a rural village in Africa. Women collecting water must still walk across the village to the well, where they often encounter long lines. The water, clean from the well, is often re-contaminated by the buckets used to collect the water or from dirty hands and poor hygiene. Trying to persuade villagers to drink water for health reasons may work for a period of time, but people are inherently lazy and if the well is not the easiest method for water collection, it will be left unused. Changing habits, especially ones ingrained into the lifestyles of villagers’ remains the greatest challenge in solving the water crisis.

Water is a women’s burden. In 70-80% of households, collecting water for the family falls on the mother or daughter. Professor Banerjee gave me examples of the gender segregations and challenges in persuading men to respect the water and use it only as necessary. He said men wash their hands in the water meant for drinking often wasting and contaminating it. They show a lack of respect for the struggles of women to provide drinking water for their families. Breaking traditions or culture makes implementing solutions very difficult. For example, the walk, although dangerous, time consuming and grueling, gives women a chance to talk and connect with each other. Scale is another problem faced in finding solutions. Where one implementation method or solution may work in one village, scaling the solutions to suit the hundreds of villages that need water often does not work. Scaling is also difficult when faced with varied environmental factors such as rainfall. For example, in monsoon areas such as Bangladesh or India, there are periods of flooding contrasted with times of drought. In many of these cases water storage become an effective solution. In contrast, many areas in Africa are very dry with not enough water and bad distribution. Dealing with the water crisis is not going to become easier in the future. As climate change leads to more extreme weather patterns, and population growth adds to the stress on the Earth’s natural resources, solving the water crisis is going to become more, not less, challenging. Currently there are more people in the world with a mobile phone than a toilet. One project from Change Lab is currently trying to scale interventions by using the cell phone penetration in India to provide incentives, such as an education for children, to persuade local people to sign on to their water catchment project. Innovative ideas that combine new technologies with the ingrained cultures in developing nations are essential to move forward in the goal for clean, accessible water for all.

The importance of engaging local people in the creation and implementation of solutions was highlighted in another class I took this quarter, Biosecurity and Bioterrorism Response. The main obstacles in setting up a sustained development program are the people. An example from my Biosecurity class came in a lecture discussing the challenges U.S. officials faced when helping European nations, especially the Former Soviet Union and Georgia, to improve their biodefense research conditions. Providing sustainable aid to secure and improve conditions in labs is much harder than building a new research facility that often becomes too expensive for the country to maintain. One challenge was trying to ensure that the Georgians and Russians agreed with the U.S. protocols in securing and cleaning up labs. The U.S. often sent young, female officials to persuade 60-year-old Russian men to change their habits. Invariably this led to strained relations purely because in Russian culture age and gender play a large role in hierarchy and older Russian men are not receptive to advice, regardless of its importance, from younger women. In this example, if the US had understood and respected the culture differences it is likely that sustained change would have occurred much faster and with fewer difficulties.

Never Stop Learning

“Creativity is inventing, experimenting, growing, taking risks, breaking rules, making mistakes and having fun”

Beginning my Stanford career I never imagined that an art project would be one of my favorite experiences of my undergraduate career. There were moments when I felt as though someone in TSR would realize I was not an artist and lacked creative talent or insight. But I learnt this year that creativity is one of my gifts and TSR gave me the opportunity to develop this skill. The yearlong project took me on a discovery of the artistic process. Upon seeing my final fountain, my artistic mentor, Jeremiah Barber, said to me that people would not understand the struggles and challenges that went into the piece. I realized that this is true generally in art. Upon viewing the final work the audience often does not appreciate how much time, thought and effort went into the piece. TSR gave me a new appreciation for how I view art and the challenges artists face. In addition, I learnt through this process how little control an artist has over the audience and how the artwork is received. Terry Berlier talked about how the audience will often take something completely different away from her art than she had intended. She rarely shares the meaning or story behind her art with the audience (for example her story about her Aunts). I wonder how the Stanford community has received my fountain and if many people have stopped by on their way to class to read about the message behind it.

Reaching out to artists and the water community at Stanford forced me out of my comfort zone. It gave me the opportunity to meet and connect with new and different people. In TSR I made new friends and developed a bond with my classmates and professors that I had not previously experienced in my academic work at Stanford. TSR took me on a journey of personal development mostly because of the different type of education and the new people I was exposed to on the way. I mentioned earlier that my over ambitious nature was the reason for the failure of my hand built pot and one of my biggest lessons this year. I discovered through this project that what might be considered my biggest weakness is also a great strength. If I had chosen the safe option, a smaller design or a painting, I may have never learnt my capabilities to deal with failure. Working through the challenges of my project gave me the confidence to continue to strive for seemingly impossible results. The rejection of my grant proposal was a turning point in my project. Re-evaluating my reasons behind the proposed piece illuminated my personal instinct to find solutions to problems. Initially the only purpose I considered for my project was trying to raise awareness to help solve the water crisis. In personal relationships, I often have a similar reaction and try to help friends by suggesting solutions. While this may be helpful in some cases, sometimes all my friends need is someone to listen and sympathize. The Senior Reflection made me realize that personal searching is a development in education, interactions and experiences. Although my career at Stanford may be coming to a close, my journey of self-reflection will never truly end.