Research Discussions:

The following log contains entries starting several months prior to the first day of class, involving colleagues at Brown, Google and Stanford, invited speakers, collaborators, and technical consultants. Each entry contains a mix of technical notes, references and short tutorials on background topics that students may find useful during the course. Entries after the start of class include notes on class discussions, technical supplements and additional references. The entries are listed in reverse chronological order with a bibliography and footnotes at the end.

June 15, 2013

We spent the last three months studying how to get detailed information out of the brain at sufficient quantity and quality that would make it interesting, even necessary to apply industrial-scale computing infrastructure to analyze and extract value from such data. If we were thinking about launching startup, the next step would be to formulate a business plan to define and motivate a specific project and the staffing required to carry it out. Concretely, we might start by taking a close look at the investment opportunities identified in the report we produced in CS379C this quarter.

As an exercise, I will tell you how I would tackle the problem of formulating a business plan for launching a project at Google. I’m using the term “business plan” rather broadly here to include prospects for scientific research; the “business” aspect of the plan is that the project has to make sense for Google to invest effort. Specifically, it has to be something that has significant societal or scientific merit and only Google could carry it off by leveraging its infrastructure and expertise, or it offers new opportunities for growth in existing product areas or developing new revenue streams that make sense for Google financially and technologically.

In the following, I’ll elaborate on an idea we talked about in class and that I believe has promise by offering (a) a new approach to computational neuroscience that leverages what Google does best — data-driven analytics and scalable computing, (b) opportunities to make significant advances in the knowledge and methodology of neuroscience, and (c) the possibility of discovering new algorithms for machine learning and pattern recognition and new approaches for building efficient computing hardware.

I maintain, based on investigations over the last nine-months and discussions with some of the best systems neuroscientists in the world that we will soon — within at most a couple of years — have the ability to record from awake, behaving mammals — mouse models are just fine — data that can be used to recover spikes at unprecedented spatial and temporal scale.

I’m currently focusing on two technologies that we talked about in class. The first technology involves advances in 3-D microarrays for electrophysiology that leverage CMOS fabrication to achieve 10 micron resolution in z, 100 micron resolution in x and y, and millisecond temporal resolution [51]. New optogenetic devices may supersede this technology in a few years with more precise tools for intervention and new options for recording [176], but for now we can depend on a relatively mature technology accelerated by Moore’s law to sustain us for the next couple of years.

The second technology involves the use of miniaturized fluorescence microscopes that offer ~0.5 mm2 field of view, and ~2.5 micron lateral resolution according to Ghosh et al [59]. The fluorescence imaging technologies have lower temporal resolution and more difficulty in recovering accurate spike timing [160], but offer better options for shifting the field of view, i.e., could be done mechanically or optically versus removing and then inserting the probe in a new, possibly overlapping location as would be required in the case of an implanted 3-D probe, and less tissue damage and potential for infection limiting the effective duration of chronic implants.

Collecting data would precede as follows: First, identify a 3-D volume of tissue in the experimental animal’s brain which we’ll refer to as the target circuit and position the recording device so that it spans a somewhat larger volume completely enclosing the target circuit. Identify the “inputs” and “outputs” of the target circuit, which for the purpose of this discussion we assume correspond to, respectively, axonal and dendritic processes intersecting the boundaries of the target. Collect any additional information you may need for subsequent analysis, e.g., we might want to identify capillaries to use as landmarks if there is a plan to subsequently sacrifice the animal and prepare the neural tissue for microscopy in order to collect static connectomic and proteomic data.

Record as densely as is feasible and especially at the boundaries of the target tissue while the experimental animal is exposed to test stimuli aligned with the neural recordings for subsequent analysis. Note that it isn’t necessary to record from specific cells or locations on cells, e.g., a uniformly spaced grid of recording locations, while implausible, would work fine for our purposes. The above-mentioned recording technologies should make it possible to collect extensive recordings of each animal, and running many animals in parallel should be possible using modern tools for automating experimental protocols [38, 175]. Finally, if applicable, prepare the tissue for staining and scanning to obtain additional provenance relating to structure (connectomics and cell-body segmentation) and function (proteomics and cell-type localization).

Now we want to learn a function that models the input-output behavior of the target tissue. Specifically, we are interested in predicting outputs from inputs in the held-out test data. I don’t pretend this is going to be easy. In the simplest approach we would ignore all the data except on the target boundaries. Knowing the types of cells associated with the inputs and outputs might help by constraining behavior within cell-type classes. In a more complicated approach, we might be able to recover the connectome, use it to bias the model to adhere to connectomically-derived topological constraints and treat the sampled locations other than those on the boundary as partially-observable hidden variables. As I said, this isn’t likely to be easy, but rather than trying to use theories about how we think neurons work to bias model selection, I’m interested in seeing what we can accomplish by fitting rich non-parametric models such as the new crop of multi-layer neural networks [91, 94].

Given how hard this problem to likely to turn out in practice, I think it wise to start out on training wheels. I suggest we begin by developing high-fidelity simulations for in silico experiments using technology such as MCell which is able to incorporate a great deal of what we know about cellular processes into its simulations [143, 37]. Unlike the attempts at simulating a single cortical column conducted by the EPFL / IBM Blue Brain collaboration, we envision starting with an accurate model of cytoarchitecture obtained using electron microscopy coupled with proteomic signatures synapses obtained from array tomography. In any case, we would want to start with much simpler target circuits than a cortical column consisting of 60,000 cells.

Once we have a reasonably accurate simulation model for target circuit, the next step would be to “instrument” the model to simulate the technologies we plan to use in our in vivo experiments. Since our models are at the molecular level it should be possible in principle simulate electrophysiology and calcium imaging. Given the resulting simulated version of our experimental paradigm, we would proceed to collect data controlling for the size and complexity of the target circuits as well as our ability to accurately record from and collect supplementary structural and functional meta data. A first step for a startup would be to build or adapt the requisite tools and create the models necessary to perform such in silico experiments and demonstrate some initial successes in recovering function from simulated neural tissue.

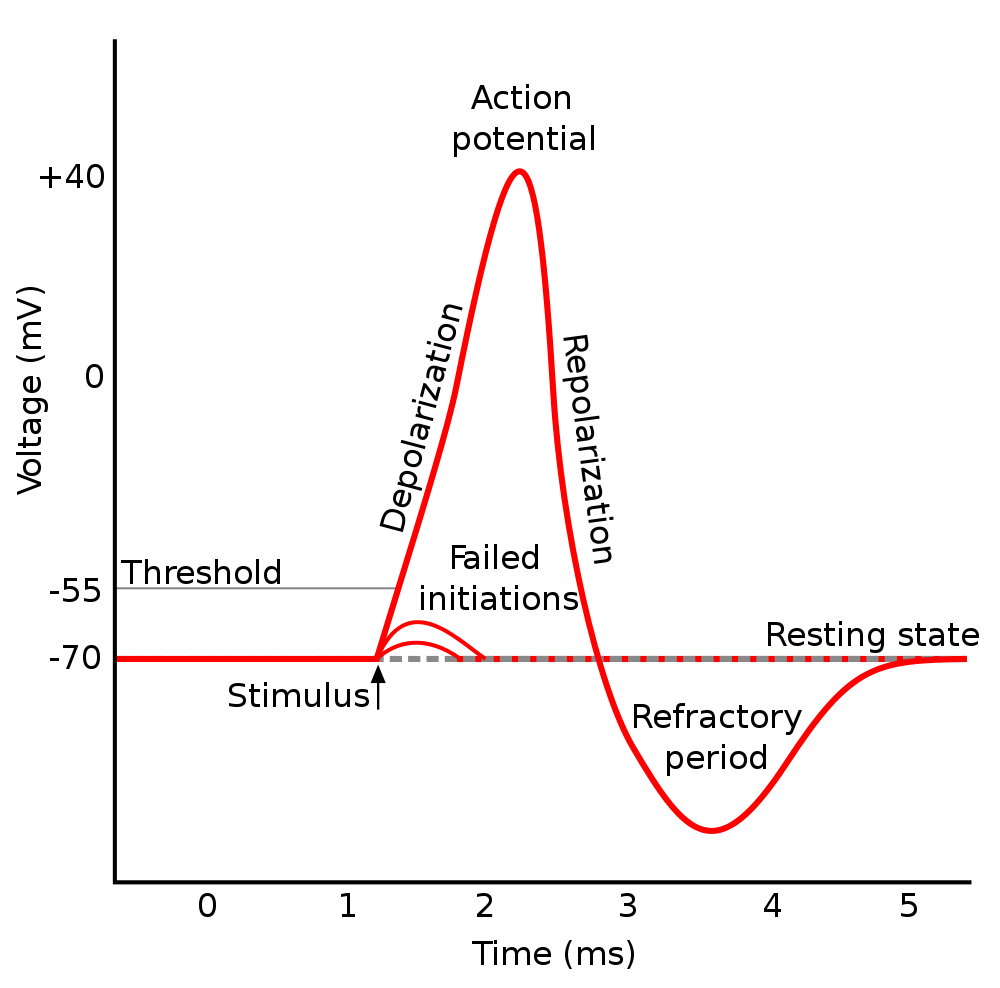

P.S. July 16, 2013: Most of the students in this year’s class had engineering backgrounds and knew basic electromagnetic and electrical-circuit theory, but I did have some questions about electrophysiology and biological neural models from people who ran across these pages on the web. I told them enough to answer their immediate questions and pointed them to some relevant textbooks and Wikipedia pages to continue their education. Below is a mashup of my responses included here as a starting point for other visitors to these pages — most of the content is in the footnote. If this is too much technical detail, you might consider the electric-hydraulic analogy which for all its shortcomings often helps to make simple circuits more comprehensible and intuitive.

The primary tools of the electrophysiologist include the voltage clamp which is used to hold the voltage across the cell membrane constant so as to measure how much current crosses the membrane at any given voltage, the current clamp in which the membrane potential is allowed to vary and a current is injected into the cell to study how the cell responds, and the patch clamp which is a refinement of the voltage clamp that allows the electrophysiologist to record the currents of single ion channels. To understand the technical details of these methods, you will need a basic understanding of elementary electromagnetic theory1

June 9, 2013

I asked Justin Kinney, a postdoc in Ed Boyden’s lab, about using their new probes for recording from mouse cortical columns. Here’s what he had to say followed by my posting to CS379C and Mainak’s reply:

JK: Our custom silicon probes are planar arrays of 64 to 128 gold pads per shank (100 microns wide by 15 microns thick and 1-2 mm in length). The pads are 10 microns in a side with a 15 micron pitch, with the possibility of shrinking both dimensions. We are experimenting with different ways to maintain a low electrical impedance of the pad, e.g., 1 Mohm, even as we shrink the size of the pads. To keep tissue damage at reasonably low levels, we must space the shanks pretty far apart, e.g, 100s of microns. So the question of brain coverage — can we record from every neuron in a volume — becomes a question of the “field of view” of an individual shank. How large is the volume of brain tissue around a probe for which the activity of every neuron is accurately recorded? We do not know the answer to this question yet. We have experiments planned which should give us some clues.TLD: So, it seems that resolution in z — along the shank — is pretty good (15 microns) but in x and y it’s pretty poor (100’s of microns). The 3-D optogenetic device described in Zorzos et al [176] looks to have similar constraints though the probes are somewhat thicker (65 microns) presumably to accommodate the light guides. I would think calcium imaging using the Schnitzer lab’s miniaturized fluorescence microscopes would be a better option in trying to instrument a cortical column, ~0.5 mm2 field of view, and ~2.5 micron lateral resolution according to the Ghosh et al 2011 paper. Lower temporal resolution I expect but perhaps less problematic in terms of shifting the field of view, i.e., could be done mechanically or optically versus removing and then inserting the probe in a new location as would be required in the case of the device that Justin describes.

What is the temporal resolution and is it dominated by the microscope hardware, GECI characteristics or the computations involved in spike-sorting and sundry other signal processing chores? Lateral resolution could be improved significantly with better CMOS sensors according to Ghosh et al [59]. What do you think?

MC: I think the characteristics of the transient Calcium response (i.e. kinetics of the GECIs) are more important than microscopic hardware or the algorithms employed. All localizing (or spike sorting) algorithms I have seen for spike train recovery use some sort of a deconvolution step which essentially amounts to undoing the spread due to the non-ideal kinetics (see here for representative response curve). This is regardless of the sophistication of the microscope or algorithms.

Improving the microscopic hardware may give us better fields of view (thereby helping us scale up the number of neurons), algorithms may give us better ability to distinguish cells based on patterns (spatial filters for image segmentation), but when it comes down to recovering precise spike timings of a population of neurons from filtered waveforms, I think that the time spread due to calcium kinetics impose critical limitations.

As an aside, there is a body of work called finite-rate-of-innovation signal recovery (e.g. see here) which can help us recover the amplitudes and time shifts of waveforms like ∑iN ai exp ( - (t - ti)). This is a constrained model, but one thing it tells us is that if the number N of independent neurons is known, one can recover the spike timings precisely (thereby implying that GECI kinetics are not a limitation anymore for temporal resolution). However I am not sure how robust this would be to noise or model imperfections.

JK: Globally, yes, the x and y resolution, defined as the distance between shanks of a multi-shank probe, is 100s of microns (as we imagine it now to keep tissue damage low). However, on a single shank, we tighly-pack pads in multiple columns, likely 2 to 4. Such a probe will sample the brain in globally-sparse, locally-dense way. I attached a photo taken through a microscope of a two-column shank.

As you point out, calcium imaging typically has larger fields of view than electrophysiology probes. On the other hand, calcium-indicator dyes generally have poor temporal response (even GCaMP6) and low-pass filter the neural activity. We are working on an experiment to perform simultaneous two-photon calcium imaging and ephys recordings (with our custom probes) to better understand the limitations of each technology.

June 7, 2013

Here are some follow-up notes from Thursday’s class addressing questions that were raised in discussions relating to Daniel’s and Mainak’s projects. The first topic relates to recycling and garbage collection in the brain:

Inside the cell, organelles called lysosomes are responsible for cleaning up the debris — digesting macromolecules — left over from cellular processes. For example, receptor proteins from the cell surface are recycled in a process called endocytosis and invader microbes are delivered to the lysosomes for digestion in a process called autophagy. Lysosomes contain hydrolase enzymes that break down waste products and cellular debris by cleaving the chemical bonds in the corresponding molecules through the addition of water molecules.

In the extracellular matrix, macrophages take care of garbage collection, by ingesting damaged and senile cells, dead bacteria, and other particles tagged for recycling. Macrophages tend to be specialized to specific tissues. In the central nervous system, a type of glial cell called microglia are the resident macrophage. In moving through extracellular fluid in the brain, “if the microglial cell finds any foreign material, damaged cells, apoptotic cells, neural tangles, DNA fragments, or plaques it will activate and phagocytose the material or cell. In this manner, microglial cells also act as ‘housekeepers’ cleaning up random cellular debris” (source).

Following our class discussion about toxicity and metabolic challenges induced by adding cellular machinery for recording, I got interested in reviewing a lecture by Robert Sapolsky entitled “Stress, Neurodegeneration and Individual Differences” from his “Stress and Your Body” series [134]. Sapolsky notes — around 33:30 minutes into the video — that “over and over again in neurological insults, all hell breaks loose, you can still carry on business pretty well, you just can’t afford to clean up after yourself”, by which he means intracellular housecleaning.

Relating housecleaning to stress, the point is that stress-induced levels of glucocorticoids damage the hippocampus by altering the ability of its cells to take up energy and then causing the cells to do more work generating waste products in the process, thereby leaving the cell depleted of energy and littered with waste that would require even more energy to recycle or expel from the cell if the cell could afford it. The cell is left exhausted and at the mercy of apoptotic and autophagic mechanisms responsible for induced cell death.

Sapolsky begins by describing the cascade of physiological events precipitated by a stress-inducing stimuli. The first steps involve the hypothalamus which contains a number of small nuclei that serve to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. In the classic neuroendocrine cascade, the hypothalamus releases CRF and related peptides which stimulate the pituitary to releases ACTH which stimulates the adrenal glands to release glucocorticoids — see here for a discussion of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis.

Glucocorticoids inhibit glucose uptake and glucose storage in tissues throughout the body except for exercising muscle. The mechanism — described 27:30 minutes into the video — works as follows: Glucocorticoids bind to their receptors on the cell surface, translocate to the nucleus where they induce the production of a protein called sequestrin that sequesters glucose receptors off of the cell surface in a process akin to endocytosis, sticking them into “intracellular mothballs”, and resulting in a cell that doesn’t take up as much glucose.

Sapolsky’s lab determined that — in the case of neurons — the reduction in glucose uptake is on the order of 20% and, in the case of sustained chronic stress, this level of reduction inevitably leads to cell death. The reason I mention this bit of esoteric knowledge here, apart from the fact that the related science is interesting, is because this sort of interaction is quite common in neuropathologies and underscores the dangers of stressing neurons with their tightly-controlled metabolic budgets.

The second topic concerns the problem of instrumenting cells in specific neural circuits for the purpose of targeted recording and relates to some issues raised by Mainak:

The cortical minicolumn is a vertical column of cortical tissue consisting of up to several hundred neurons. The minicolumn and related macrocolumn — also called hypercolumn or cortical module — has been the subject of several interesting and often controversial hypotheses about cortical computations the best known of which is generally credited to Vernon Mountcastle [116, 115, 114, 113] — the Wikipedia article is technically wanting but the Buxhoeveden and Casanova review article [28] is reasonably thorough.

We briefly discussed the minicolumn as a target circuit that would exercise near- to medium-term recording technologies, and be small enough that it might be possible to infer something interesting about its function from detailed recordings. The challenge we debated was how to record from exactly one minicolumn in an awake, behaving model such as a mouse. A minicolumn is on the order of 28-40 μm and most 2-D microelectrode arrays (MEA) are on the order 5-10 mm and the latest 3-D optogenetic array from Boyden’s lab is on the order of a couple of millimeters with about 150 μm resolution along one of the x or y axis and perhaps a tenth of that along the z axis and the other x or y axis [176].

There is a collaboration of physicists from Drexel University and neuroscientists from the Boston University Medical Campus studying the spatial organization of neurons obtained from thin-sliced brain tissue sections of rhesus monkey brains to better understand the organization of macrocolumns and minicolumns and the connection between loss of such organization and cognitive declines seen in normal aging [39]:

It has [...] been noted that different cortical regions display a “vertical” organization of neurons grouped into columnar arrangements that take two forms: macrocolumns, approximately 0.4-0.5 mm in diameter [114], and [...] minicolumns approximately 30 microns in diameter [75].Macrocolumns were first identified functionally by Mountcastle [...], who described groups of neurons in somatosensory cortex that respond to light touch alternating with laterally adjacent groups that respond to joint and/or muscle stimulation. These groups form a mosaic with a periodicity of about 0.5 mm. Similarly, Hubel and Wiesel [...] using both monkeys and cats discovered alternating macrocolumns of neurons in the visual cortex that respond preferentially to the right or to the left eye. These “ocular dominance columns” have a spacing of about 0.4 mm. In addition, they discovered within the ocular dominance columns smaller micro- or minicolumns of neurons that respond preferentially to lines in a particular orientation.

Once these physiological minicolumns were recognized, it was noted that vertically organized columns of this approximate size are visible in many cortical areas under low magnification and are composed of perhaps 100 neurons stretching from layer V through layer II. To prove that the [...] morphologically defined minicolumns [...] are identical to the physiologically defined minicolumn would require directly measuring the response of a majority of the neurons in a single histologically identified microcolumn, but this has yet to be done. (source)

Probably worth thinking about whether any of the existing MEA technology would be of use in recording from a mouse minicolumn, or whether alternative technology like the Schnitzer lab’s micro-miniature (~2.4 cm3) fluorescence microscope would make more sense given its ~0.5 mm2 imaging area and maximum resolution of around 2.5 microns [59]. As for a method of selecting exactly the cells in a cortical minicolumn, apart from just recording densely from a region large enough to encompass a minicolumn, subsequently sacrificing the animal and then scanning the tissue at a high-enough resolution to identify the necessary anatomical details, I can’t think of anything simple enough to be practical.

June 5, 2013

Andre asked a professor from University of Texas Austin about some of the RF issues and his answers might help those of you working on related technologies to organize your thoughts and identify important dimensions of the problem.

AE: I’m taking a class in neuroscience in which we’re employing nanotechnology ideas to solve the problem of getting data out of the brain. Imagine we have a small optical-frequency RFID chip in each brain neuron, constantly sending out information about whether the neuron is firing or not, in real time. There are 1011 or 100 billion neurons, that is, 1011 RFIDs sending information optically to some receiver outside the skull.Do you happen to know of a sophisticated scheme which might allow us to deal with the issue of reading in 1011 transmitters sending information between ~214 THz and 460 THz (the biological ‘transparency’ window of 650-1400 nm wavelengths). I can envision frequency division multiplexing with (460 THz – 214 THz) / 1011 neurons = 2460 Hz per neuron, but I may be neglecting other issues, such as SNR or the ability to transmit in such a narrow window at such high frequencies.

BE: Large-scale problem. Fun exercise to think through despite the many current insurmountable barriers for such a system.

Scenario #1: Sensors are transmitting all of the time: For frequency division multiplexing, you had mentioned a transmission bandwidth of 2460 Hz per sensor. Assuming sinusoidal amplitude modulation, the maximum baseband message frequency would be 1230 Hz. If this were digital communications, then the sampling rate would be 2460 Hz at the sensor of the neural activity.

Scenario #2 — On-Off Keying: To save energy, each sensor could use on-off keying. Only transmit something when the neuron has a spike. It saves on transmit power and reduces interference with other transmitters. You could still use frequency division multiplexing as before.

Scenario #3 — Wishful Thinking: Since we’re assuming the design, fabrication and implantation of 1011 sensors, we could assume the design and fabrication of 1011 receivers. Each would be tuned to one implanted sensor. This would help workaround the problem of a single receiver trying to sort out 1011 transmissions, which is not practical.

Scenario #4 — Frequency Allocation: It would be helpful if the transmission frequency band for a particular sensor is not close to the transmission bands of the sensors closest to it. There is always some leakage into other bands. For on-off keying, I recall that the leakage strength reduces versus frequency away from the sensor’s transmission band.

June 3, 2013

The audio for our discussion with Mark Schnitzer is now linked off the course calendar page. Thanks to Nobie and Anjali for recalling Mark’s references to Stanford scientists doing related work:

Ada Poon’s group with respect to RF techniques in tissues,

Bianxiao Cui’s group with respect to cultured neuron interfaces,

Nick Melosh’s group with respect to cultured neuron interface, and

Krishna Shenoy’s group with respect to neural prostheses in primates.

The reference to Ada Poon’s lab led me to several papers incuding this review of methods for wireless powering and communication in implantable biomedical devices [169].

We talked briefly at the end of class about the possibility of giving up on “wireless” and instead trying to figure out a way of installing a network of nanoscale wires and routers in the extracellular matrix. Such a network might even be piggybacked on the existing network of fibrous proteins that serve as structural support for cells, in the same way that the cable companies piggyback on existing phone and power distribution infrastructure. There was even a suggestion of using kinesin-like “linemen” or “wire stringers” that walk along structural supports in the extracellular matrix to wire the brain and install the fiber-optic network.

Perhaps it’s a crazy idea or, as someone pointed out, perhaps someone will figure out how to do this and, in the future, it will just be “obvious” to everyone. I did a cursory search and, in addition to some related ideas from science fiction stories, I found this Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory announcement of the 2013 Wiring the Brain Meeting scheduled for July 18 through July 22. It’s about how the brain’s neural network is wired during development; not exactly what I was looking for, but a timely reminder that nature might have some tricks worth exploiting. I also found this 2009 review paper [90] on nanomaterials for neural networks that has interesting bits about toxicity and nanowires.

Anjali and I talked after class about differences in the terminology surrounding ultrasound, specifically the acronyms for therapeutic ultrasound technologies — FUS, HIFU, USgFUS and MRgFUS and low-intensity US for stimulation — versus the diagnostic/imaging ultrasound technologies. I asked her to send me the names of a relevant contacts at Stanford and she supplied: Dr. Kim Butts-Pauly, Dr. Pejman Ghanouni, Dr. Urvi Vyas, and Dr. Juan Plata-Camargo.

We also discussed the ambiguity concerning the “imaging” category used in the paper, and Anjali suggested that I was “using imaging as a term encapsulating any externally recording, computing, and powered device rather than only the modalities that result in images” which I thought was a good characterization of my intent2.

May 31, 2013

It is no longer necessary to depend solely on what we discover in the natural world when searching for biomolecules for engineering purposes. Methods from synthetic biology like rational protein design and directed evolution [21] have demonstrated their effectiveness in synthesizing optimized calcium indicators for neural imaging [73] starting from natural molecules. Biology provides one dimension of exponential scaling and additional performance can be had by applying high-throughput screening methods and automating the process of cloning and testing candidates solutions. There are also opportunities for accelerated returns from improved algorithms for simulating protein dynamics to implement fast, accurate, energy function used to distinguish optimal molecules from similar suboptimal ones. Advances in this area undermine arguments that quantum-dots and related engineered nanoscale components are crucial to progress because these technologies can be precisely tuned to our purposes. Especially when weighed against the challenges of overcoming the toxicity and high-energy cost of these otherwise desirable industrial technologies.

Following Wednesday’s discussion, I’m a little concerned about how the analysis of the readout problem is progressing, i.e., the readout solutions that might be leveraged by advances in nanotechnology. In particular, I want you to be convinced by Yael’s and Chris Uhlik’s arguments that an RF approach doesn’t scale — in particular, see if you agree Chris’s back-of-the-envelope analysis as it seems to be more completely worked out than Yael’s analysis. Make sure you’re OK with their assumptions. If you agree with them, then it’s fine to say so and summarize their analysis and credit them in your report, e.g., use a citation like “Uhlik, Chris. Personal Communication. 2013”.

When and if you’re convinced, apply the same standards that you used in evaluating RF solutions in evaluating possible optical solutions. It’s not as though we can’t imagine some number of small RF transmitters implanted deep within the brain or strategically located inside of the dura but on the surface of the brain. These transmitters could number in the thousands or millions instead of billions and serve relatively large portions of the brain with additional local distribution via minimally-invasive optics of one sort or another — diffusion might even work if the distances are small. Broadcasting in the RF, these transmitters would have no problem with scattering and signal penetration depth. The problems with RF have more to do with bandwidth, practical antenna size for nanoscale devices and limited frequency spectrum available for simultaneous broadcast.

In the case OPIDs with LCD-mediated speckle patterns, even if you assume you could build a device that worked, i.e., could flash the LCD and some external imaging technology (perhaps inside the skull but outside the brain) could analyze the resulting light pattern and recover the transmitted signal, there is still the question of whether this would work with a billion such devices all trying to transmit at 1KHz. I can imagine how a small number of simultaneous transmissions might be resolved, but the computations required to handle a billion simultaneous transmissions boggles the mind — my mind at least, maybe you have a clever solution I haven’t thought of.

Make sure you’ve read Uhlik’s analysis and whatever Yael has in his slides and Adam’s notes, and then I’d like you to sketch your best solution and circulate it. Do it soon so we can all help to vet, debug, refine it, and bug our outside consultants if need be. Don’t be shy; just get something out there for everyone to think about. This is at the heart of scaling problem for readout and I’m not sure we have even one half-way decent solution on the table at this point.

By the way, to respond to Andre’s question, I have confidence that nanotechnology will deliver solutions in the long term. It isn’t a question of whether, only when. Funding will probably figure prominently in the acceleration of the field and right now biology-based solutions to biological problems have the advantage. Very successful biotech for photosynthesis-based solar power and extraordinarily efficient biofuel reactors are already eating into the nanotech venture capital pie and that could slow progress in the field. But there is room for growth and smart investors will understand the leverage inherent in harnessing extant chip design and manufacturing technologies to accelerate development:

AE: What role do you see venture capital playing in the near-term of this [neural recording] nanotechnology problem? It seems to me that things are largely still on the research end. Even when I look at the 2-5 year time frame, I can only see ventures such as non-toxic organic quantum dot mass production, assuming it is worked out.TLD: I’m thinking of a two-prong approach: (1) non-biological applications in communications and computing where biocompatibility isn’t an issue and current technologies are up against fundamental limitations, and (2) biological applications in which the ability to design nanosensors with precisely-controllable characteristics is important.

Regarding (1) think in terms of QD lasers, photonics, NFC, and more-exotic-entangled-photon technologies for on-chip communication — 2-D and 3-D chips equipped with energy-efficient, high-speed buses that allow for dense core layouts communicating using arbitrary, even programmable topologies.

Regarding (2) there is plenty of room for QD alternatives to natural chromophores in immunoflorescence imaging, voltage-sensing recording as discussed in Schnitzer’s recent QD paper in ACS Nano [103], and new contrast agents for MRI. The ability to precisely control QD properties will fuel the search for better methods of achieving biocompatibility and attract VC funding.

May 29, 2013

We discussed the format for the final projects so they would serve both for the individual student contributions to the jointly-authored technical report and also final-project document:

Three pages allotted for the jointly-authored technical report excluding bibliography:

For each technology deemed of sufficient merit for inclusion in the technical report or requiring discussion to offset unwarranted enthusiasm indicated in published reviews provide:

a summary description of the technology,

the rationale for inclusion in the report, and

a summary of the back-of-the-envelope analysis that led this rationale.

Additional pages as needed to cover the assigned topic for the final project:

For each technology considered of interest, whether or not it is included in the three pages for the technical report, provide:

a detailed description of the technology,

an extended rationale, and

the full back-of-the-envelope analysis with justification for any simplifications and order-of-magnitude estimates.

The latest version of the technical report includes drafts of the sections on “imaging”, “probing”, “sequencing” and new subsection on investment opportunities. Still left to go are the “automating” and “shrinking” sections, the latter of which we outlined in class identifying several areas requiring careful treating in the final version of the technical report. In particular:

Make clear the practical disadvantages of relying on diffusion as a mechanism for efficient information transfer in the cell contrary to its description as a solution in published descriptions of nanoscale communication networks.

Work out the issues concerning GECIs versus semiconductor-based quantum dots and related inorganic, compatibility-challenged non-biological solutions. This came up when it was noted that GECI technology and the GCaMP family in particular are improving at a rapid pace and the old arguments that natural biological agents are inferior to semiconductor-based quantum dots are being over turned as our ability to engineer better GECIs by accelerated natural selection matures [73].

What I was calling “accelerated natural selection” and “controlled evolution” in class is better known as protein engineering in the literature and generally qualified as pertaining to one of two related strategies: “rational protein design” and “directed evolution”. This was the method discussed in the paper from Janelia Farm on the optimizations that led to GCaMP5 [73].

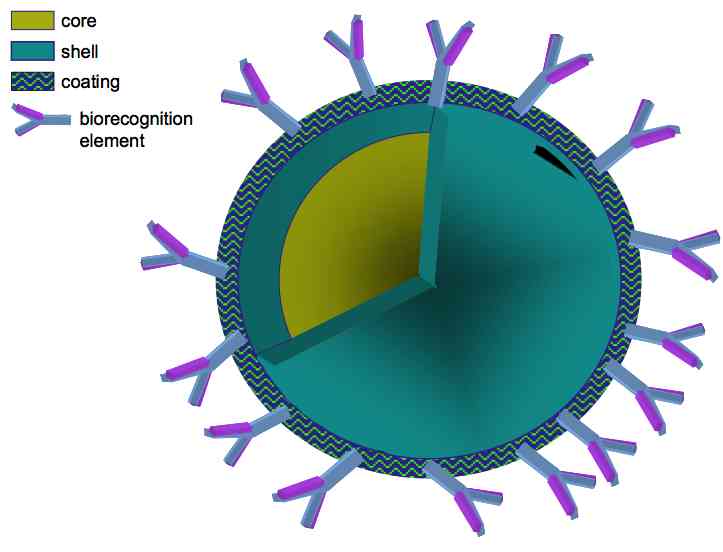

Noting that any of the nanotechnologies we discussed would require some method “installation” and that suggesting we encourage the development of “designer babies” with pre-installed recording and reporting technologies would be awkward and likely misunderstood at best, we came up with the following simple protocol for installing a generic nanotechnology solution:

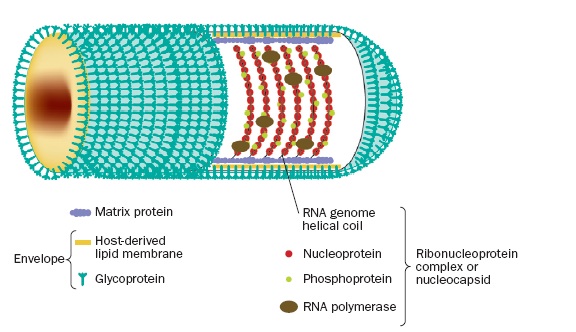

modifications of individual cells to express bio-molecular recorders using a lentivirus or alternative viral vector and recombinant-DNA-engineered payload,

distribution of OPID devices using the circulatory system and, in particular, the capillaries in the brain as a supply network with steps taken to circumvent the blood-brain-barrier, and

the use of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) “subroutines” to control gene expression for molecules used in “pairing” neurons with their associated reporter OPID devices.

It is worth noting that a more natural method of “installation” might indeed involve a developmental process patterned after the the self-assembly processes that govern embryonic development, but thus far our understanding of molecular self assembly is limited to the simplest of materials such as soap films and even in these cases nature continues to surpass our best efforts.

Relating to our discussion of the steps in the above protocol, Biafra sent around the following useful links:

protecting macromolecules: PEGylation, liposomes, doxil is a drug example, etc;

conjugating macromolecules and nanoscale devices: review article, nanopores, several lab-on-a-chip type technologies (see 1, 2, 3, 4);

adapting molecular imprinting to nanoscale devices: (see this paper);

linking biological molecules: Streptavidin, Biotin, “click chemistry” (see this review);

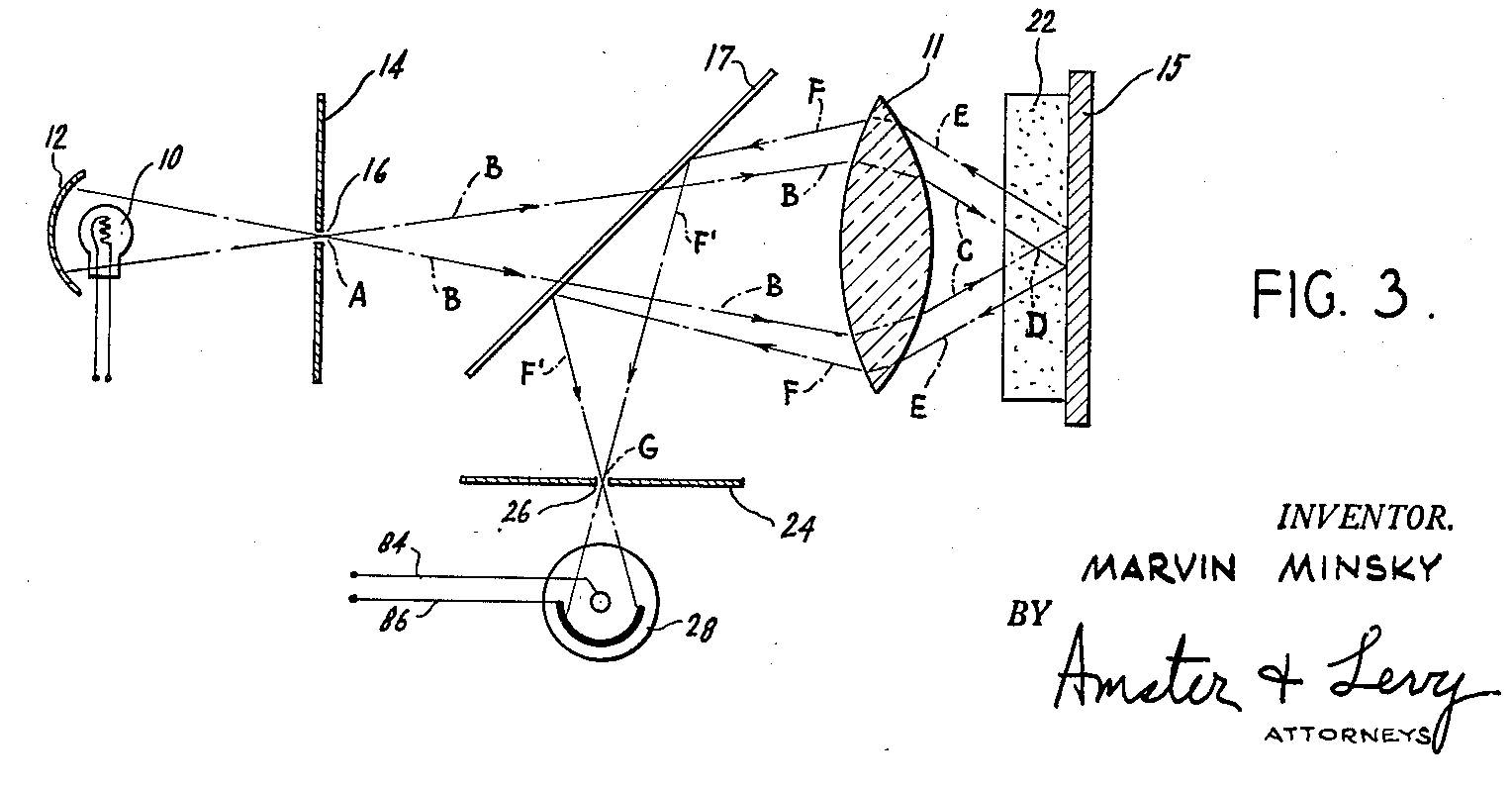

Apropos of Wednesday’s assignment to read [22], you might want to check out this recent article [139] in Nature on Kark Deisseroth. Here are a couple of quotes from Mark Schnitzer’s papers on their fluorescence micoendoscopy technology relevant to this afternoon’s class discussion:

“The Schnitzer group has recently invented two forms of fiber optic fluorescence imaging, respectively termed one- and two-photon fluorescence microendoscopy, which enable minimally invasive in vivo imaging of cells in deep (brain) areas that have been inaccessible to conventional microscopy.” [13]“Gradient-index (GRIN) lenses [...] deliver femtosecond pulses up to nanojoule energies. Why is it that confocal endoscope designs do not extend to multiphoton imaging? Over SMF [single mode fiber] lengths as short as 1-10 cm, femtosecond pulses degrade as a result of the combined effects of group-velocity dispersion (GVD) and self-phase modulation (SPM).” [78]

On a completely unrelated note, I was impressed with Daniel Dennett’s comments about consciousness following his recent talk at Google discussing his new book entitled “Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking”:

“I do not think that [consciousness] is a fundamental category that splits the universe into two. I think the idea that it is is deeply rooted in culture and may be right, but I think that consciousness is like reproduction, metabolism, self repair, healing, blood clotting; It is an interestingly complex, deeply recursive biological phenomenon [...] I think that [human consciousness] is software, it has to be installed the implication being that [...] If a human baby could be raised completely cut off from human contact, without language, and could grow to adulthood without the benefit of all the thinking tools that would normally be installed in the course of just growing up in a social community, then I think that human being would have a mind so profoundly different from ours that we would all agree that human being wasn’t conscious [in the human sense].”

May 19, 2013

Biafra sent along these examples of computations performed in biology that hint at what might be mined from detailed studies of biological organisms [145, 80]. That each paper examines a different algorithmic approach on a different computational substrate underscores the fact that we need to be open minded when looking for computation in biology [3, 135] and creative in coming up with applications that make sense. The tools that were used in extracting these programming pearls (the title of a book and a column for the Communications of the ACM magazine written by Jon Bentley) are in stark contrast with those available to Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, George Gamow and others trying to figure out how DNA eventually produced protein. I went back and read the relevant sections of Horace Freeland Judson’s The Eighth Day of Creation [77] to get some feeling for what it was like to unravel this puzzle using the available technology and what was known at that time.

Today we know about messenger and transfer RNA. We know that amino acids are coded as triplets consisting of three bases drawn from {A,C,G,U}, the same bases as DNA except uracil (U) replaces thymine (T). We know the code for amino acids is redundant and includes (3) stop codons, and that the remaining (61) coding codons specify twenty essential amino acids. But when Brenner, Crick and Gamow were trying to decipher the code they knew comparatively little about the molecular structure of proteins and the details of cellular biochemistry. Communication was more often than not by snail mail, made all the more painful with Brenner in South Africa, Crick in Cambridge and Gamow and Watson flitting back and forth between the UK and the East and West coast in the US. Bench scientists were inventing the reagents and protocols we take for granted today and while X-ray crystallography was relatively advanced it had limitations and you first had to know what you wanted to look at — they had to deduce the existence of ribosomes and infer the number of bases per codon.

May 15, 2013

Akram Sadek talked about his work [133] on multiplexing nanoscale biosensors using piezoelectric nanomechanical resonators. Audio for the class discussion is on the course calendar page and Akram promised to send his slides. Between the audio and slides and the three papers assigned for class I think you have plenty of background to understand his multiplexer technology in some detail. I think we were all intrigued with his description of how carbon nanotubes conjugated with DNA to render them biocompatible might be embedded in cell membranes and used as voltage sensors and to excite and inhibit individual neurons. Moreover the prospects to carry out interventions using RF rather than light as in the case optogenetics offers the potential to sense and intervene deep within tissue and without drilling holes in the skull.

Note that there is quite a bit of work on using nanotubes for drug and probe delivery. Wu and Philips [167] describe the development of single-walled nanotubes as a carrier for single-stranded DNA probe deliver. They claim their method offers superior biostability for intracellular applications including protection from enzymatic cleavage and interference from nucleic acid binding proteins. Their study “shows that a single-walled carbon nanotube-modified DNA probe, which targets a specific mRNA inside living cells, has increased self-delivery capability and intracellular biostability when compared to free DNA probes. [The] new conjugate provides significant advantages for basic genomic studies in which DNA probes are used to monitor intracellular levels of molecules.” Ko and Liu [85] report work on organic nanotubes assembled from single-strand DNA used to target cancer treatment.

I suggested the idea of inserting thin fiber-optic cables tipped with a MEMS device attached to a prism / mirror. The MEMS device could be powered by light and controlled to point the mirror in a particular direction or to scan the surrounding tissue in the vicinity of the probe’s tip. As in the case of Ed Boyden’s 3-D probes, this arrangement could be used for both transmitting and receiving information. The fiber-optic tether is crucial given the power requirements of such a device fabricated using current technology, but it would be interesting to think about the prospects for using implantable lasers and powering the MEMS device wirelessly.

Yesterday morning, I talked with George Church about his Rosetta Brain idea. The Allen Mouse Brain Atlas is an amalgam of hundreds of mouse brains. In contrast, the Rosetta Mouse Brain would combine four maps of a single mouse: connectomic, transcriptomic and proteomic information in addition to measurements of cellular activity and developmental lineage. George believes this could be accomplished in a year or so using his method of fluorescent in situ sequencing (FISSEQ) on polymerase colonies. He believes that the total funding required would be something on the order of $100K and that he could do it in his lab. George is on the west coast a couple of days each month and will be in the Bay area in June for a conference. He also mentioned that he, Ed Boyden and Konrad Kording have applied for BAM/BRAIN money to pursue their molecular ticker-tape work which he predicts will have it’s first proof-of-concept demonstration within a year.

May 13, 2013

In today’s class, we discussed class projects and, in particular, the proposals that are due next Monday at noon. Note that the due date has changed; it seems that not all of you keep late night hours and so I extended the deadline to noon. This entry will be a hash of follow-up items from our class discussion. Note that I expect your proposals to reflect the original list of top-ten promising technologies and the comments from our invited speakers and technical consultants.

First off, here are some links relevant to BAM/BRAIN that might be useful in understanding how the initiative is viewed from the perspective of two key federal agencies, NIH and NSF. And, apropos our discussion of commercial applications of BAM/BRAIN technologies, here’s an example of an interesting company in the BCI space. Ariel Garten, the CEO of InterAxon spoke in Ed Boyden’s Neurotechnology Ventures course at MIT last Fall. The title of his presentation was “Thought-controlled computing: from popular imagination to popular product.” Here’s their website splash page:

|

Relating to Mainak and Ysis’ project focus, Justin Kinney is a good contact in Ed Boyden’s group working on strategies for neural signal acquisition and analysis. At the Salk Institute, he worked on three-dimensional reconstructions of brain tissue from serial-section electron microscopy images, and his dissertation at UCSD involved the development of software for carrying out accurate Monte Carlo simulations of neuronal circuits (PDF). This last is relevant to some of Nobie’s interests.

Also relevant to cell-body segmentation is the work of Viren Jain [74] who worked with Sebastian Seung at MIT and collaborated with Kevin Briggman and the Denk lab. Viren is now at HHMI Janelia Farm and recently gave a talk at Google that you might find useful to review along with Kevin’s presentation available from the course calendar page. You can find more recent papers at Viren’s lab at Janelia and Sebastian’s lab at MIT. The relevant algorithms involve machine learning and diverse techniques from computer-vision including superpixel agglomeration and superresolution.

Doing back-of-the-envelope calculations will play a key role in your course projects. For a classic example of a back-of-the-envelope calculation, see Ralph Alpher and George Gamow’s analysis of how the present levels of hydrogen and helium in the universe could be largely explained by reactions that occurred during the “Big Bang” (VIDEO). I mentioned Chris Uhlik’s back-of-the-envelope analysis of using RF for solving the readout problem: his analysis short, to the point, and worth your time to check out; you can find his notes here.

I had wanted to do an exercise in class in which we scale the human brain to the size of the Earth, but we ran short of time. The intent was to have you do all of the work, but I had some rough notes to help grease the wheels that I include below. I started with some comments about where you can find quantitative information. In cases where there is an established engineering discipline various companies and professional societies often provide resources, e.g., the BioSono website provides tissue-density tables, transducer simulations and a host of other useful tools and data for the engineer working on medical ultrasound imaging. In neuroscience, academic labs often compile useful lists of numbers that neuroscientists find useful to keep in mind, e.g., see Eric Chudler’s list at University of Washington.

As a concrete example, dendrites range in diameter from a few microns at the largest (e.g. the primary apical dendrite), to less than half a micron at the smallest (e.g. terminal branches). The linear distance from the basal end to the apical end of the dendritic tree usually measures in the hundreds of microns (range: 200 μm to over 1 mm). Because dendrites branch extensively, the total dendritic length of a single neuron (sum of all branch lengths) measures in centimeters.3 Now let’s see how we might use this information in our exercise to rescale the brain to be around the size of the Earth.

The Earth is about 12,742 km in diameter, which we’ll round off to 10,000 kilometers. Let’s say a human brain is 10 cm or 0.1 m on a side and so our scale factor is 100,000,000:1. The diameter of a neuron (cell body) is in the range of 4-100 μm [granule,motor] and so let’s call it 10 μm and its dendritic span could be more than a millimeter. In our Earth-size scaled brain, the diameter of a neuron would be around 1 kilometer and its axonal and dendritic processes could span ten times that or more. So now we have a neuron the size of a small town and its axonal and dendritic processes spanning a small county. What about smaller entities?

A molecule of glucose is about 0.5 nm and a typical protein around 5 nm. Synaptic vesicles can contain upwards of 5,000 molecules of small-molecule neurotransmitter like acetylcholine. Think of these relatively small molecules as being on the order of a meter in size. Bigger than a loaf of bread and smaller than a 1969 Volkswagen bug. Recall that some cellular products are manufactured in the soma and transported along microtubules to be used in the axons. What would that transport system look like?

The outer diameter of a microtubule is about 25 nm while the inner diameter is about 12 nm. These tubular polymers of tubulin can grow as long as 25 micrometres and are highly dynamic. Think of the outer diameter of the microtubule being around the width of a small-gauge railroad track. What about even smaller entities? Ions vary in size4 depending on their atomic composition and whether they have a negative or positive charge, but typical values range from 30 picometers (1012 m) (0.3 Ångström) to over 200 pm (2 Ångström). In our planet-sized brain, ions are on the order of a millimeter. Still visible but just barely.

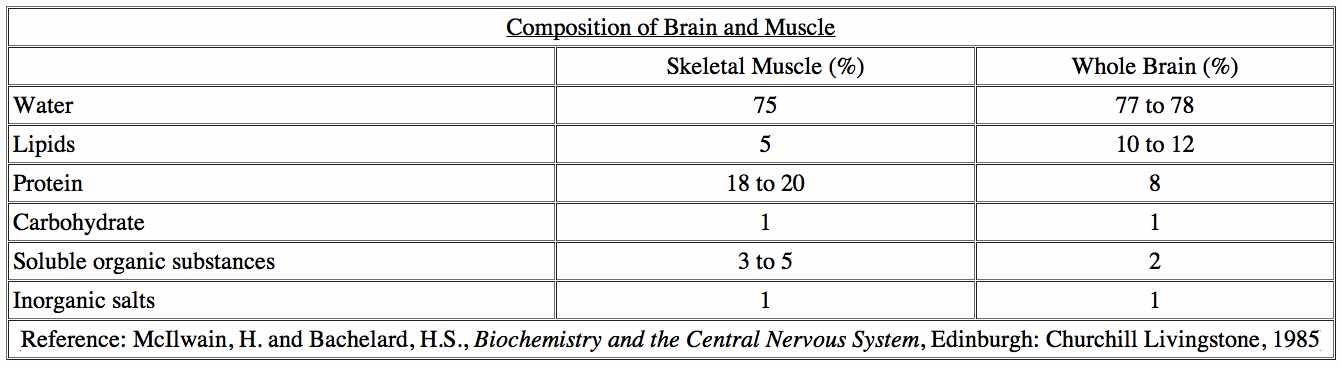

Intracellular fluid, the amount of water that’s inside our cells, accounts for something between 2/3rds and 4/5ths of our total volume, and so it follows that the extracellular fluid, the amount of water that surrounds our cells, accounts for between 1/5th and 1/3 of our total volume. Approximately 78% of the brain consists of water. The rest is comprised of lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and salts. The ratio of grey to white matter — which consists mostly of glial cells and myelinated axons — is about 1.1 in non-elderly adults; myelin is about 40% water; the dry mass is about 70-85% lipids and about 15-30% proteins.

The inside of cells is crowded with molecules moving around due to the forces of Brownian motion, diffusion, and the constant making and breaking of covalent bonds that serve alter molecular shapes. Some compartments and organelles are more congested than others, but these forces dominate in the propagation of information and its physical manifestation — proteins, ion concentrations — in the central nervous system. Try to imagine what this world would look like if you could walk through our Earth-size brain and watch DNA polymerase at work replicating DNA in the cell nucleus or signal conduction in a synapse.

In our planet-sized brain, we can imagine using communication satellites and cellular networks to transmit and receive information, cell phones and RFID devices using wireless, bluetooth and NFC (near-field communication) for local information processing and intra-cellular communication. It is an interesting exercise to consider Chris Uhlik’s back-of-the-envelope analysis assuming for the purpose of the exercise that your readout technologies could use the macroscale physics of a planet-sized brain while the massive brain would miraculously continue to operate using microscale physics of biology. It’s a stretch, but a good exercise.

Apart from preparing for the above thought experiment which we didn’t even end up talking about in class, I also wrestled a bit more with how to frame the reporting problem and the technologies that you’ll be investigating in your projects. In the spirit of writing sections of the paper many times in preparing for the final version, here are some of my thoughts: Without getting too abstract, energy and information are at the heart of what we’re up against; positively in terms of powering recording and reporting technologies and defining informational targets, and negatively in terms of compromising tissue health and producing noise that interferes with signal transcoding and transmission.

One way or another, we have to (a) expend energy to measure specific quantities at specific locations within the tissue, (b) expend energy to convert raw measurements into a form suitable for transmission, (c) expend energy to transmit the distilled information to locations external to the tissue, and, finally, (d) expend energy to process the transmitted information into a form that is useful for whatever purpose we have in mind, whether that be analyzing experimental results or controlling a prosthetic. Each of these four steps involves some form of transduction: the process of converting one form of energy into another.

In the case of imaging, typically all of the required energy comes from sources external to the tissue sample. Electromagnetic or ultrasonic energy is used to illuminate reporter targets and then reflected energy is collected to read out the signal. We can complicate the picture somewhat by using the energy from illumination to initiate cellular machinery to perform various information processing steps to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the return signal. We can go a step further and use the illumination energy to power more complicated measurement, information-processing and signal-transmission steps.

Alternatively, we can figure out how to harness cell metabolism and siphon off some fraction of the cell’s energy reserves to perform these steps. In the case of external illumination, the tissues absorb energy that has to dissipated, as thermal energy. In the case of depleting existing cellular energy, the brain already uses a significant fraction of the body’s energy and operates close to its maximum capacity. In either case, if we are not careful, we can alter the normal function of the cell thus undermining the whole endeavor.

The human brain, at 2% of body mass, consumes about 20% of the whole body energy budget, even though the specific metabolic rate of the human brain is predictably low, given its large size. Source: Herculano-Houzel, S. Scaling of Brain Metabolism with a Fixed Energy Budget per Neuron: Implications for Neuronal Activity, Plasticity and Evolution. PLoS ONE (2011). The brain’s use of glucose varies at different times of day, from 11 percent of the body’s glucose in the morning to almost 20 percent in the evening. In addition, different parts of the brain use different amounts of glucose.

Several factors make it difficult to identify specific metabolic requirements. First, we know the brain is constantly active, even at rest, but we don’t have a good estimate of how much energy it uses for this baseline activity. Second, the metabolic and blood flow changes associated with functional activation are fairly small-local changes in blood flow during cognitive tasks, for example, are less than 5 percent. And finally, the variation in glucose use in different regions of the brain accounts for only a small fraction of the total observed variation. Source: Raichle, M.E., Gusnard, D.A. Appraising the brain’s energy budget. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (2002). (PDF)

May 11, 2013

There are eight students taking the course for credit. I took the initial list of proposed top-ten promising technologies and tried to group them in related pairs. We’ll revisit this grouping during class discussion on Monday, in preparation for which you should also review the comments from our invited speakers and technical consultants. I ended up with four pairs and two singletons and then I made a first pass to assign each of you to one of these six categories.

All of this preliminary organization is up for discussion and indeed whatever technologies you end up taking responsibility for in your final project and the proposed technical report, I expect that you will consult with each other on other technologies depending on your particular expertise. Here are my initial assignments: (#1 and #5) piggybacking on medical imaging — Anjali, (#2 and #6) finessing imaging challenges — Nobie, (#4) implantable and steerable arrays — Daniel, (#3 and #8) robotics and computer science — Mainak and Ysis, (#7) leveraging genome sequencing — Biafra, and (#9 and #10) advances in nanotechnology — Oleg and Andre. And here is a simplified version of the previously circulated list aligned with the above-mentioned indices for easy reference:

near-term advances in imaging for human studies — MRI, MEG, FUS, PAI, PET, SEM, etc. — (1-2 years)

development of new animal models — transgenic fly, mice, zebrafish, etc. – (2-3 years)

automation using machine learning and robotics — electron microscopy, animal experiments, etc. — (1-2 years)

advanced fiber-optically coupled multi-cell recording — coupled 3-D arrays, microendoscopy — (2-3 years)

intermediate-term advances in imaging broadly construed — MRI, FUS, SEM, etc — (2-3 years)

new contrast agents and staining preparations — MRI, CLARITY, ultrasound — (2-3 years)

leveraging advances in genome-sequencing — DNA barcoding, molecular ticker-tapes — (3-5 years)

computation-intensive analytics — cell-body segmentation, spike-coding, simulations — (1-2 years)

semiconductor-based recording with optical readout — quantum dots, FRET technology, etc — (3-5 years)

implantable bio-silico-hybrids, wireless or minimally-invasive fiber-optic readout — (5-10 years)

Miscellaneous topics that might be worth addressing in the technical report:

Translational medicine: mouse and human studies and investment in the technologies that support them;

Evolution of mature technologies and how to accelerate development of promising nascent technologies;

Technological opportunities and predicted time-lines for the longer-term impact of nanotechnology;

Potential for significant infusion of investment capital to spur innovation akin to genome sequencing;

I’m often chided for having a “reductionist” philosophy in terms of my scientific and technological outlook, and so I enjoyed the following excerpt from The Rapture of the Nerds: A tale of the singularity, posthumanity, and awkward social situations by Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross. Huy, the book’s protagonist, is an uploaded human in a post-singularity era in which most of the humans and all of the “transcended” humans exist in simulated worlds that are run on a computational substrate constructed from extensive mining of the solar system.

Just prior to the exchange described in the excerpt, she — Huy started the book as a flesh-and-blood human male but was slotted into a female simulacrum in the upload process — asks her virtual assistant referred to here as the “Djinni” how to adjust her emotional state and is presented with an interface replete with cascading selection menus and analog sliders of the sort you might find in a studio recording mixer.

The book is full of obscure science fiction references, and the following excerpt refers to a fictional device called a “tasp” that induces a current in the pleasure center of the brain of a human at some distance from the wielder of the tasp. In Larry Niven’s novel Ringworld, these devices are implanted in the bodies of certain members of an alien race known as Puppeteers for the purpose of conditioning the humans they have to deal with in order to render them more compliant. Here’s the excerpt:

“I hate this,” she says. “Everything it means to be human, reduced to a slider. All the solar system given over to computation and they come up with the tasp. Artificial emotion to replace the genuine article.”The Djinni shakes his bull-like head. “You are the reductionist in this particular moment, I’m afraid. You wanted to feel happy, so you took steps that you correctly predicted would change your mental state to approach this feeling. How is this different from wanting to be happy and eating a pint of ice cream to attain it? Apart from the calories and the reliability, that is. If you had practiced meditation for decades, you would have acquired the same capacity, only you would have smugly congratulated yourself for achieving emotional mastery. Ascribing virtue to doing things the hard, unsystematic way is self-rationalizing bullshit that lets stupid people feel superior to the rest of the world. Trust me, I’m a Djinni: There’s no shame in taking a shortcut or two in life.”

May 9, 2013

Yesterday’s class discussion with Brian Wandell was timely. Brian started by making a case for more emphasis on human studies. First, he claimed that only 1/3 of 1% of mouse studies result in human drug or clinical-treatment trials. Without data on how many human studies result in such trials, this statement is a bit hard to put in perspective, but it is sobering nonetheless. It would also be useful to have statistics on how often a promising molecule or intervention found in a study involving a mouse model translates to a corresponding result in humans. I asked Brian for relevant papers and he suggested two [62, 153] that look promising.

To underscore the differences between human and mouse models, Brian mentioned that myelinated axon tracts in the mouse brain are far less common than in human brains — or, more precisely, the fraction of total brain volume occupied by white matter is significantly less in mice — in part because the distances involved in the mouse are considerably shorter and hence faster signal conduction is less advantageous. He also mentioned differences in the visual systems and retina; human eyes converge to focus and have high acuity in the foveal region while mice tend to diverge to gain greater field of view and their retinal cells exhibit less diversity tending to behave for the most part like the human retinal cells responsible for our peripheral vision. This reminded me of Tony Zador’s comment that humans and more highly-evolved organisms tend toward more specialized functions facilitated by complicated genomic pathways involving more promoters and switches than the corresponding protein-expression pathways in simpler organisms.

Having motivated the study of human brains, he turned his attention to one of most powerful tools for studying human cognition. Brian summarized how fMRI is employed in studying cognitive function in humans, including normal and pathological behaviors involving perception, language, social interaction, executive function, affective disorders including anxiety and depression, and developmental aspects of the aforementioned. I promised to include a pointer to the work of Stanislas Dehaene and so here are some of Dehaene’s technical papers and books [47, 46, 44, 45], the last of which Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention is an excellent introduction to the research on reading that Brian talked about in his presentation.

Brian also provided background on the basic physics of NMR, how it’s applied in the case of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and how his lab is attempting to improve resolution and extend the class of neural signals it is possible sample with this technology. The multi-plane parallel-imaging technology5 soon to be available will accelerate imaging four-fold, and perhaps there are even greater gains to be had in the future. Speed definitely matters in both clinical and scientific studies. A friend of mine just recently had to endure an MRI scan that required him to remain still for 45 minutes and would have been very grateful had Stanford employed the new technology Brian told us about. Biafra Ahanonu recommended this website maintained by Joseph Hornak at the University of Rochester as a convenient resource and introduction to MRI.

At the workshop sponsored by The National Science Foundation & The Kavli Foundation entitled “Physical and Mathematical Principles of Brain Structure and Function”, Huda Zoghbi spoke (PDF) eloquently about the need to “know all of the components of the brain, not just neurons” and that we need know how these components connect and communicate and most important “how brain activity varies with experiences and external stimuli.” She points to the Allen Institute and the foundation it has established in developing the paradigms and open-source resources for the Mouse Brain Atlas. I found her discussion of the MeCP2 gene instructive in light of Brian’s comments about mouse studies. MeCP2 causes Rett syndrome whose symptoms range from loss of language and social skills around two years of age to inability to control movement. I think one could argue that preliminary effort expended on MeCP2 in mouse models was well spent, if it ultimately assists in human studies.

She opines that “biology, genome projects, and neuroscience have taught us the value of the model organism” and that “we need to continue to capitalize on this.” And then a little later, citing the work of Helen Mayberg who used MRI analysis of white matter to study the difference between patients suffering from depression who respond to deep brain stimulation and those who don’t, she suggests that “somehow we need to make the research more iterative between humans and the lab.” Elsewhere Zoghbi posits that it is hard to argue that “technology development wasn’t a major part of the genome project” citing Ventner’s use of genome-wide shotgun assembly which “came mostly from improvements in algorithms, longer read lengths and computational power” and observes that the “benefits of the influx of bioinformatics due to the genome project have spread well beyond genome science. She suggests to the participants that we need to “think about what technology needs to be developed [for BAM/BRAIN], and what portion of [NSF] funding needs to be set aside for technology development.”

In this interview with Sydney Brenner — see Part 1 and Part 2, Brenner called Craig Ventner’s synthetic organisms “forgeries” likening them to the Vermeer forgeries by Han van Meegeren, and expressed his belief that we’re drowning in data and starving for knowledge — paraphrasing John Naisbitt in his 1982 book Megatrends, and that all this Bayesian analysis and cataloguing was so much bean counting and stamp collecting without meaningful theories, by which I think he meant something more akin to the Bohr or Rutherford models of the atom than to quantum electrodynamics with its reliance on probabilistic wave functions.

Similar sentiments were expressed by the participants of the workshop mentioned earlier. On the first day of the workshop all of the participants were given the opportunity to express their interests relating to BAM/BRAIN in one minute or less. The audio for those sessions are available here and here if you’re interested. No neuroscientist in this day and age is going to say publicly that theory does not deserve a central role in the brain sciences — the words “hypothesis” and “theory” often used interchangeably are inextricably linked to the scientific method. That said I think a case can be made that what constitutes a meaningful theory may have to be expanded to include new ways of thinking about the sort of complex emergent phenomena that characterize many biological and social processes.

Perhaps our craving for elegant, easily communicated theories/stories speaks to inherent limitations in our cognitive capacity. The search for general principles — the holy grail of modern science — sounds so reasonable until you ask scientists what would qualify for such a principle, and here I suspect you’d get very different answers depending on whom you ask. For example, would Donald Hebb’s proposed mechanism for synaptic plasticity or Francis Crick’s central dogma of molecular biology pass muster with most neuroscientists if they were proposed today? We would like the world to be simple enough accommodate such theories, but there is no reason to expect that nature or the cosmos will cooperate. Perhaps in studying complex systems like the brain, ecosystems or weather, we’ll have to settle for another sort of comprehension that speaks more to the probabilistic interactions among simpler components and characterizations of their equilibrium states without a satisfying account of the intermediate and chaotic annealing processes that seek out these equilibria.

Moreover, complex emergent phenomena like those produced by living organisms can only fully be explained in the context of the larger environment in which the relevant systems evolved, e.g., adaptations to a particular constellation of selection pressures. In some circles, the term “emergent” is often use derisively to imply inexplicable, opaque or even mystical. As for “stamp collectors”, the modern day scientific equivalent of the naturalists who collected species of butterflies or ants in the Victorian age, consider Craig Ventner’s sailing the world’s oceans in search of new organisms, molecular biologists looking for useful biomolecules, e.g., channelrhodopsin, to add to their toolkit for manipulating life at the nanoscale, and virologists on the quest to discover the next interesting microbe. And I would add another potentially fruitful avenue for future exploration. Why not search for useful computational machinery as revealed in cellular circuits (not just neurons) to solve algorithmic problems on computational substrates other than biological ones?

May 7, 2013

In motivating faster, less expensive methods for extracting the connectome, Tony Zador offered several scientific assays that connectomes would make possible. For example, he described work by Song et al [140] from Chklovskii’s lab analyzing how local cortical circuitry differs from a random network. They discovered that (a) bidirectional connections are more common than expected in a random network and (b) that certain patterns of connectivity among neuron triples were over represented. These experiments were extremely time-consuming and Tony pointed out that considering patterns involving more than three neurons would be prohibitively time consuming. He also noted that large-scale spectral graph analysis would be feasible with a complete connectome and that finding patterns such as those revealed in the Song et al work could be carried out easily with the connectome adjacency matrix.

Tony then described the core idea — recasting connectomics as a problem of high-throughput DNA sequencing, his inspiration — Cold Spring Harbor is a world-renowned center for the study of genomics and he had sat through many talks by visitors discussing sequencing and analyzing the genomes of various organisms, and, finally, his education in molecular biology and its acceleration during conversations with his running partner Josh Dubnau, a molecular biologist and colleague at Cold Spring Harbor lab. We had already covered the basics — a multi-step process consisting of (a) barcoding individual neurons, (b) propagating barcodes between synaptically-coupled neurons, (c) joining host and invader barcodes and (d) sequencing the tissue to read off the connectome — from reading his earlier paper [172], and were primarily interested in progress on those problems that were not adequately addressed in that earlier paper.

He began with a review of the earlier work and outlined his strategy for validating his method. His ultimate goal is the mouse connectome — ~105 neurons, not all stereotyped and roughly as complex as a cortical column, but his interim goal is to sequence the connectome of C. Elegans — 302 neurons and ~7,000 stereotyped connections — for which we already have ground truth thanks to the heroic work of Sydney Brenner6 and his colleagues [165]. This two-organism strategy introduces formidable challenges as his technique must apply to both a mammal and a nematode with different neural characteristics and, in particular, different susceptibility to viruses of the sort Zador proposes to use to propagate information between neurons.

He talked briefly about adding locality and topographic annotations to the connectome. Some locality will fall out of slicing and dicing the tissue into 3-D volumes a few microns on a side to be sequences individually thereby associating barcoded neurons with locations in 3-D space, but he also mentioned the idea of barcoding neuron-type information thereby labeling individual neurons and sequencing this along with the barcoded connectomic information. In response to a related comment by Adam Marblestone in an earlier post, I sketched Tony’s proposed method and initial proof-of-concept experiments — see here.

Tony then launched into a discussion of barcoding beginning with the basics of using restriction enzymes to cut a plasmid vector at or near specific recognition nucleotide sequences known as restriction sites in preparation for inserting a gene or, in our case, a barcode. He first described the relatively easy case of in vitro cell cultures and then took on the challenge of in vivo barcoding which is complicated by the requirement that the random barcodes must be generated in the cells. Given a standard template corresponding to a loxP cassette, the goal is to randomize the template nucleotide sequence by applying one or more operators that modify the sequence by some combination of insertion, deletion, substitution and complementation operations.

Cre recombinase, a recombinase enzyme derived from a bacteriophage, is the tool of choice for related applications. Unfortunately Cre performs both inversion — useful in randomizing a sequence — and excision — not so useful as it shortens the sequence yielding an unacceptable O(n) level of diversity : “DNA found between two loxP sites oriented in the same direction will be excised as a circular loop of DNA whilst intervening DNA between two loxP sites that are oppositely orientated will be inverted.” The solution was to find a recombinase that performs inversion but not excision.

Rci recombinase, a component in the aptly named shufflon inversion system, was found to fill the bill yielding a theoretical diversity of O(2n n!) and an in vivo experimental validation that more than satisfied their requirements. Employing a model in which a lac promoter was used turn Rci expression on or off, they ran a control with Rci off resulting in no diversity and then a trial with Rci turned on that produced the desired — exponential-in-the-length-of-the-template — level of diversity. The initial experiments were done in bacteria. Rci also works in mammals and subsequent experiments are aimed at replicating the results in a mouse model.

Next Zador provided some detail on how they might propagate barcodes transynaptically using a pseudorabies virus (PRV). PRV spreads from neuron to neuron through the synaptic cleft. The PRV amplicons are plasmids that include a PRV “ORI” sequence that signals the origin of replication and a PRV “PAC” sequence that signals what to package. They can be engineered so that they don’t express any viral proteins thus rendering them inert at least in isolation. A helper virus is then used to initiate synaptic spread in a target set of neurons.

The in vivo experiments were reminiscent of the circuit-tracing papers out of Ed Callaway’s lab, dealing, for example, with the problem of limiting spread to monosynaptic partners — see for example [30, 105]. Researchers in Tony’s lab have replicated Callaway’s rabies-virus experiments using their pseudorabies virus, and so there is ample precedent for the team succeeding with this step in the overall process. The final step of joining host and invader barcodes into a single sequence was demonstrated in a very simple experiment involving a culture of non-neuronal cells and then in another in vitro somewhat more complicated proof-of-concept experiment.

In this second experiment, two sets of embryonic neurons were cultured separately, one with the PRV amplicon alone and a second with PRV amplicon plus the φ31 integrase enzyme which was introduced to mediate the joining of host and invader barcodes. Then the two cultures were co-plated and allowed to grow so as to encourage synaptic connections between neurons, the cells are infected with PRV thus initiating transynaptic transfer of barcodes between connected neurons, and, finally, after a sufficient interval of time to allow the connections to form, the sample is prepared, the DNA amplified by PCR and the result sequenced. Without accurate ground-truth, it is impossible to evaluate the experimental quantitatively, but qualitatively the resulting connectome looked reasonable.

There is still some way to go before the Zador lab is ready to generate a connectome for C. Elegans, but they have made considerable progress since the 2012 paper in PLoS in which they proposed the basic idea of sequencing the connectome. Tony also talked about alternative approaches, and we discussed how, as in the case of optogenetics, a single-molecule solution might surface that considerably simplifies the rather complicated process described above. The prospect for serendipitously stumbling on the perfect organism that has evolved an elegant solution to its survival that also solves a vexing engineering problem is what keeps molecular biologists avidly reading the journals of bacteriologists, virologists and those who study algae and other relatively simple organisms that exhibit extraordinarily well adapted survival mechanisms.

May 5, 2013