Visualizing scale: A day of Uber rides in London on April 9, 2016

Growing Fast (Perhaps Too Fast) 2015-2016

W

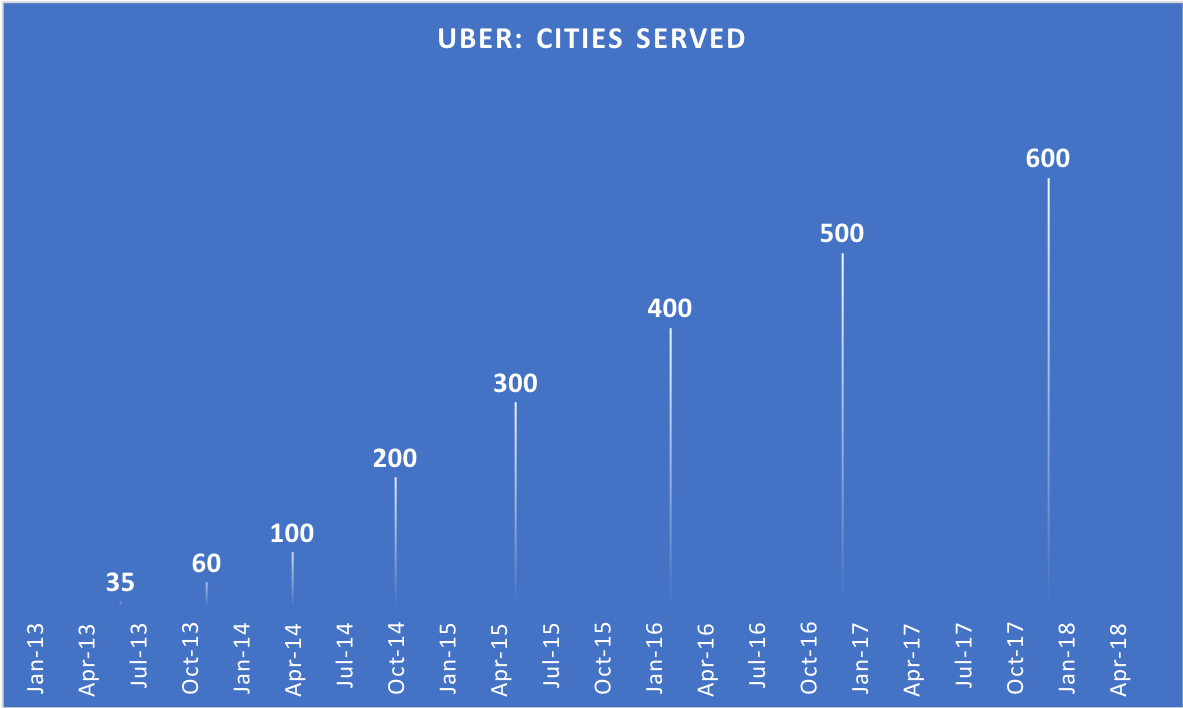

ith its decentralized operations teams and the shift to microservices, plus billions of dollars in fresh cash from venture capital investors, Uber was able to step on the gas in 2015 and 2016. The company had provided 140 million rides in 2014. By the end of 2015, it would complete 1 billion rides. And just six months after that, in June 2016, it would complete 2 billion rides.N And it wasn’t just providing more rides in the same cities. Over the course of 2015 and 2016, Uber nearly doubled the number of cities it served, from about 250 to 500.N

Uber: Growth in Cities Served, 2013-2018

Moreover, the company was expanding into new lines of business. It would incubate ideas, then hive off promising new products, like UberEats and autonomous vehicles, and let them run fast in their own silos. Headcount soared, from 550 at the beginning of 2014 to about 12,000 at the end of 2016. Managers who came into the company supervising small teams quickly found themselves leading armies.

Uber's headcount growth

Senior managers in Uber’s engineering organization recounted some of the changes as the company rapidly expanded.

Rapid Hiring

The three generations of Uber employees

“When I joined the company … in my group, there were five engineers,” recalled Srinivasan, who started at Uber in 2014. “Now, I lead a team of 600 to 700 people.”

Srinivasan was no stranger to rapid scaling; before Uber, he worked at LinkedIn. There, he grew a team from three people to 120 in three years.

“I thought that was pretty interesting growth in itself. But the scale at Uber is just much more than what I’ve seen than any other place. I actually don’t think Google or Facebook – which are the companies which I thought grew really fast -- still saw [as much] growth in relative business terms as Uber, in terms of going to so many different countries across the world with intense competition in every place. In the markets, Uber’s product looks the same. But it’s extremely fragmented because the political and regulatory environments in every country are very different.”

--Ganesh Srinivasan

Ryan Sokol, who like Srinivasan joined the company in 2014, considered himself part of the “second generation” of Uber employees. He sensed differences between his cohort and the company’s early founders, and with the employees who came after him — in terms of motivation, compensation, experience and expectations.

“The first generation is the Travis [Kalanick] generation — a bunch of people that stumbled upon a pretty kickass idea, got in way deep over their head, and just worked their butts off to make it happen and work, work, work. I mean at that time they're working 18- or 20-hour days, they're sleeping for four, and they're coming back the next day. I’ve never seen people work harder,” he recalled.

Those who came in the second wave, he said, “were probably more trained professionals. They were like, ‘Oh, this looks like a cool opportunity where I can exert some of my learnings and really see it in a product-market fit where I don't have to screw around with start-ups. I can really exert my energy.’”

Sokol had been at start-ups before and had a sense of what to expect. “I came here willing to put in my four years and grind myself to paste if I had to, because it was fun, it was engaging, and it was exciting,” he said. “Most of the people that came in the second generation of Uber came for that same reason.”

The next wave of employees, said Sokol, was motivated as well, but some were surprised by the pace and the workload. “When they got in here and they saw that it was charging so hard, I think some of them started to think, ‘Oh man, what did I sign up for?’ ”