Today: int vs float, function call / parameters, PyCharm, command line, bluescreen algorithm

These are all on HW2, due next Wed

Talk about math briefly for today, mostly int. Revisit int/float later.

You would think computer code has a lot to do with numbers, and here we are.

See Python Guide: Python Math chapter.

Surprisingly, computer code generally uses two different types of numbers - "int" and "float".

>>> 2 + 3 # ints 5 >>> 2 + 3 * 4 # Precedence 14 >>> 2 * (1 + 2) # Use parenthesis 6 >>> 10 ** 2 # 10 Squared 100 >>> 2 ** 100 # Grains of sand in universe 1267650600228229401496703205376 >>> >>> >>> 1 + 2 * 3 # int in, int out (except /) 7

>>> 2.0 * 3.5 # float in, float out 7.0 >>> 2.0 * 3.5 + 1.0 8.0 >>> >>> 2 * 3.5 + 1 # one float -> float result 8.0 >>> >>> 6.02e23 # "e" format - 1 mole 6.02e+23 >>> 6.02e23 * 2 # 2 moles 1.204e+24 >>>

Hopefully someday you'll get a job where you can save a little money for retirement. A great choice is an S and P 500 index fund, originally invented by Jack Bogle and the Vanguard Group. These have earned, say, 7% returns per yer (after accounting for inflation). So how much will your savings grow if left in there for 30 years, averaging 7% per year?

>>> 1.07 ** 30 7.612255042662042

If you have a lot of years to wait, compounding is magical.

int() float()The formal names of the types are "int" and "float". As a handy Python convention, there are functions with those names that try to convert an input to that type. The int() function just discards the fractional part of the number.

>>> int(3.6) 3 >>> float(3) 3.0

>>> 7 / 2 3.5 >>> 8 / 2 4.0

With a series of operators of the same precedence, the operators are evaluated from left to right with a so called "running number". Initially the running number is the leftmost number, then apply each operation to the running number, going from left to right. Example (click to reveal):

>>> 4 - 2 + 1

3

Python starts with 4, and does the operations one at a time, left to right - so subtracting 2, then adding 1, resulting in 3.

It's the same with multiplication and division. What is the result of this expression:

>>> 12 / 4 * 2

6.0

Start with 12, then divide by 4, yielding 3.0. Then multiply by 2, resulting in 6.0.

In this case, the answer is float 6.0 because the division operation / produces a float result, even with int inputs.

Indexing into a structure is very common, e.g. get_pixel(x, y), and in this context, the x and y will always be int.

get_pixel(x, y) - int x, yimage.get_pixel(4, 5) -> ok image.get_pixel(0, 0) -> ok image.get_pixel(2.5, 0) -> ERROR image.get_pixel(2.0, 0) -> ERROR

bit.paint('blue')

The parentheses part of the function call contains the parameter values for the function, also known as the arguments of the function.

We hand-waved how that worked before, but today we go through it in detail.

Say we have a darker_left function that takes in 2 parameters: the name of an image file, and a number. It computes a new image, darkening the number of pixels on the left of the image corresponding to the number, like this:

The structure here is we want to call a function and pass in some extra information like 'poppy.jpg' and 50 to go into the computation. This is role of parameters in Python functions.

We have the darker_left() function on the experimental server to see how parameters work.

We think of a function as a single thing, but in fact each function appears in the code in two different forms — the def form, and the call form. We'll look at them in turn...

The def has the function name and its parameters listed within parenthesis. There is only a single def for each function, but there can be many calls to that function.

def darker_left(filename, left):

...

This function has two parameters, filename and left.

What is the meaning of each parameter?

Each parameter holds a value for the code in the function to use. In this case, the filename parameter is the name of the image file to work on. The left parameter specifies the number of pixels on the left to darken.

We can say that the parameters are "coming in" to the function when it runs.

To write code within the def, assume that each parameter is ready to use. The function code simply uses each parameter, relying on the right value being in there.

Who gives each parameter a value? We will see below.

Each parameter is like a variable, and for a def like this, the variables are already set to point to appropriate values. So in this case filename and left are already pointing to the right values, and the code in the def simply uses them.

KEY - writing code in a function, the programmer should be aware of the parameters listed up on the def line. Most likely, the code within the function is supposed to use the parameter values. The parameters are an important part of the function, and the code in the function should incorporate them.

The attitude here is one of trust — the code is given filename and left and just uses them.

Here is the code with the key line missing:

def darker_left(filename, left):

image = SimpleImage(filename)

for y in range(image.height):

for x in range( ????? ):

pixel = image.get_pixel(x, y)

pixel.red *= 0.5

pixel.green *= 0.5

pixel.blue *= 0.5

return image

Q: How many pixels on the left to darken?

A: Whatever value is in the left parameter.

Key idea: the parameters filename and left are ready, so just use them by name in the code.

def darker_left(filename, left):

image = SimpleImage(filename)

for y in range(image.height):

for x in range(left): # Key line

pixel = image.get_pixel(x, y)

pixel.red *= 0.5

pixel.green *= 0.5

pixel.blue *= 0.5

return image

We are told to just use the parameter values. But where do they come from?

The parameter values come from the function call and its parenthesis. The only way a function runs is when a lines calls that function, and the call will specify the values for the parameters.

Recall that each function has two roles, def and call.

A call of a function is one line, calling the function by name to run it. The call specifies the values for the parameters within its parenthesis.

How does a function run? The only way a function runs is if there is a line somewhere that calls the function, and that line will have the parameter values.

Who provided the values to the parameters? It was you the programmer, when writing the call line.

When darker_left() function is called, the parameter values to use are written within the parenthesis. In this case the filename parameter gives the name of the file with the image to edit, e.g. 'poppy.jpg'. The left parameter specifies the number of pixels at the left side of the image which should be darkened.

Here is the Python syntax for three calls to the darker_left() function. You can see the values for the filename and left parameters within the parenthesis.

For each call to the function, we say the parameters are "passed in" to the function. So above the first calls passes in 50 for the left parameter and the last call passes in 2.

Look at the Run Menu on the experimental server for darker_left() carefully. For each case, you can see the syntax of the function call in the menu — the name of the function and a pair of parenthesis. Look inside the parenthesis, and you will see the parameters passed in for each run. Click the Run button with different menu selections to see it in action, essentially calling the function that way.

foo(a, b)What do you see here?

def foo(a, b): ... ...

It's a function named "foo" (traditional made-up name in CS). It has two parameters, named "a" and "b".

Each parameter holds information the caller "passes in" to the function when calling it. What does that look like? Which value goes with "a" and which with "b"?

A call of the foo() looks like this:

.... foo(13, 100) ...

In the function call above, values match up by position within the parenthesis.

The first value in the call is 13, so it goes to the first parameter in the def (a). When the code runs, it will see a has the value 13. The second value in the call is 100, so it goes to the second parameter in the def (b).

foo() in Interpreter> Experimental server Console Interpreter. The interpreter has a >>> prompt. The Python interpreter presents a "REPL" — Read, Eval, Print, Loop. Python reads what you type, evaluates it, prints the result, and then gives you another prompt.

def foo(a, b):

print('a:', a, 'b:', b)

We can do a little live exercise in the interpreter to see function call in action. We'll enter a little two-line def of foo(a, b) in the interpreter, then try calling it with various values. It's very unusual to define a function within the interpreter like this, but here's one time we'll do it. Normally we define functions inside a file, like image-grid.py on HW2.

The most important thing is that at the function call line, the parameter values are copied from within the parenthesis to the function parameters. The parameters match by position. So the first value goes to "a", the second value goes to "b".

Since foo() has 2 parameters, the number of values in the function call must be exactly 2 or there's an error, The word "argument" is another word for a parameter, which appears in the Python error messages.

Each parameter value can be an expression - Python computes the value if needed, then sends that value as the parameter.

Each function has its own variables and parameters, separate from the variables and parameters in other functions, even if the variables have the same name. So an "a" inside a function is different from an "a" variable in some other function. This shows up in the last example below.

>>> # Define foo

>>> def foo(a, b):

print('a:', a, 'b:', b)

>>>

>>> # Call it with 2 param values

>>> foo(1, 2)

a: 1 b: 2

>>> foo(13, 42)

a: 13 b: 42

>>>

>>> # Call with expression - passes computed value, e.g. 100

>>> foo(10 ** 2, 3 + 1)

a: 100 b: 4

>>>

>>> # Show that number of parameters must be 2

>>> foo(12)

Error:foo() missing 1 required positional argument: 'b'

>>> foo(12, 13, 14)

Error:foo() takes 2 positional arguments but 3 were given

>>>

>>>

>>> # Each function gets its own variables, so the

>>> # "b" here is separate from the "b" in foo()

>>> # Parameters do not match by name

>>> # Parameters match by position - first to "a", second to "b"

>>> b = 10

>>> b

10

>>> foo(b, b + 1)

a: 10 b: 11

>>>

Each parameter represents a piece of information the function needs in order to run. When calling the function, Python insists we provide, in the parenthesis, a value for each parameter

The command line is how your computer works "under the hood", and we'll use it in CS106A. Not fancy looking, but very powerful. In particular, to use code for data science or what have you, the command line is a powerful technique.

When you type on the command line, you are talking to the operating system of your computer. We'll use it with a free program called PyCharm to edit and run your Python programs - see the Install-Python-PyCharm instructions on the course page.

For details about the command line, see Python Guide: Command Line

The above guide has instructions to download this example folder: hello.zip

Unzip that folder. Copy the enclosed "hello" folder to your computer to work in it. (Windows: confusingly, windows will typically create two "hello" folders, one inside the other. We want the inner "hello" folder.) Go to PyCharm, and use the "open" command to open the "hello" folder (not the hello.py, the folder). In PyCharm after opening the folder, select "Terminal" at lower left - that's the command-line area.

First we'll type the command "date" into the terminal and hit the enter/return key to run it. The computer runs the "date" program, and shows its output in the terminal, and then gives us another prompt to type more commands. (In our examples "$" represents the prompt printed by the computer, waiting for you to type something.)

$ date Fri Oct 4 11:58:51 PDT 2024 $

The basic structure is: the computer prints a prompt (e.g. "$"), you type a command and hit the return key, the computer prints out a response and another prompt.

Then try the "ls" command ("dir" on old windows). The command line runs in the context of some folder on the computer - "ls" lists the files in the folder. Try the "cal" command (sorry, no equivalent on Windows).

hello.pyThe file hello.py contains a Python program.

Try running the hello.py program ("python3" on the Mac, "py" or "python" on Windows) with the command shown below. The hello.py program takes in a name on the command line, and prints a greeting to that name. It's a simple program, but it shows how programs are run and how to adjust their inputs.

$ python3 hello.py Alice Hello Alice $ python3 hello.py Bob Hello Bob $ python3 hello.py -n 100 Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice Alice

Use the up arrow in the command line to retrieve and then edit a previous line. We never re-type in a command from scratch — use the up-arrow instead. Huge time saver! Another instance of organized laziness in CS.

When typing at the command line, you are typing commands to your computer operating system - Mac or Windows or Linux. This is different from the ">>>" prompt where you are typing commands to Python, but the two have a similar type-a-command computer-prints-result structure.

Then we demo command lines from the image-grid homework. They look like this

$ python3 image-grid.py -channels poppy.jpg $ $ python3 image-grid.py -grid poppy.jpg 2 $ $ python3 image-grid.py -random yosemite.jpg 3

Those are described in detail in the image-grid homework handout, so you'll see explanations for those when you begin the homework.

Now we're going to do something cool. In typical CS106A fashion, we'll work out the algorithmic idea first, then there's the matter of translating it into Python.

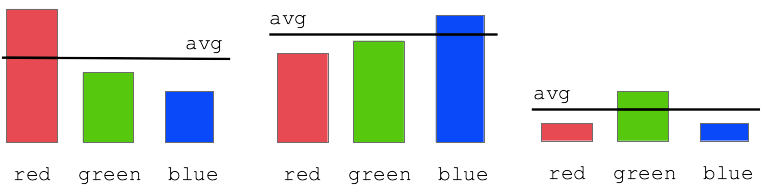

First, compute the average of red + green + blue for each pixel, like this (parenthesis are needed):

# compute average number for a pixel

average = (pixel.red + pixel.green + pixel.blue) / 3

Diagram:

This code is complete, look at the code then run it to see.

Solution code

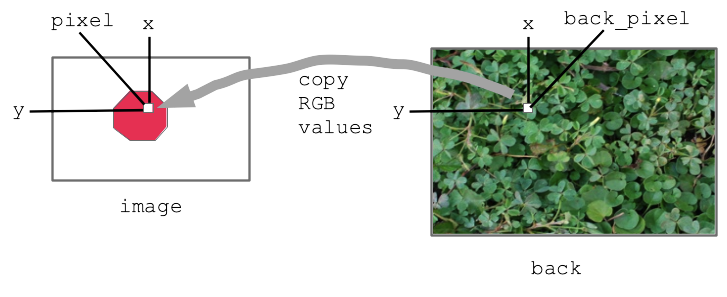

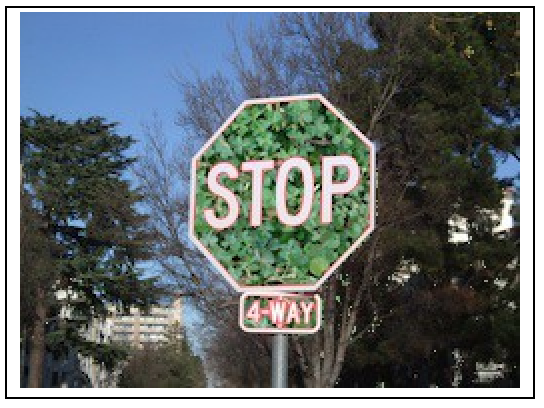

def stop_leaves(front_filename, back_filename):

"""Implement stop_leaves as above."""

image = SimpleImage(front_filename)

back = SimpleImage(back_filename)

for y in range(image.height):

for x in range(image.width):

pixel = image.get_pixel(x, y)

average = (pixel.red + pixel.green + pixel.blue) / 3

if pixel.red >= average * 1.4:

# the key line:

back_pixel = back.get_pixel(x, y)

pixel.red = back_pixel.red

pixel.green = back_pixel.green

pixel.blue = back_pixel.blue

return image

Before - the red stop sign before the bluescreen algorithm:

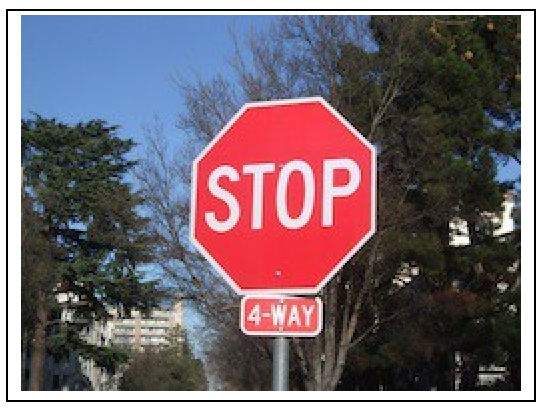

After:

A favorite old example of Nick's.

Have monkey.jpg with blue background

The famous Apollo 8 moon image. At one time the most famous image in the world. Taken as the capsule came around the moon, facing again the earth. Use this as the background.

The bluescreen code is the same as before basically. Adjust the hurdle factor to look good. Observe: the bluescreen algorithm depends on the colors in the main image. BUT it does not depend on the colors of the back image - the back image can have any colors it in. Try the stanford.jpg etc. background-cases for the monkey.

The code is complete but has a 1.5 factor to start. Adjust it, so more blue gets replaced, figuring out the right hurdle value.

This is the "front" strategy - replacing blue pixels in the front image, then the front image is the final output. There is also a "back" strategy on the HW2c handout which you have as an option. The handout also describes an optional brightness add-on for the bluescreen code, where it selects only the bright blue pixels, leaving the other blue pixels intact. This may be helpful to get certain effects in your output.

For HW2c you will make your own bluescreen, but we provide most of the code. We will have an art-show/contest with the results.

Bluescreen Contest Categories:

Best artistic

Best humor

Best use of background

Best picture of you with someone super famous