Today: modules, json, urllib, how the internet works

There are a few lines in your Python files that still need to be explained. Today we'll explain the "import" lines, e.g near the top of pylibs.py.

... import sys import random ...

Each import line brings in a module for your code to use.

A module, also known as a "library" in CS, gathers together code for common problems, ready for your code to use. For example the math module contains mathematical functions like sin(), cos().

# Bring in the "math" module

import math

...

Python itself has the basic loop/string etc functionality. And there are modules that contain ready to use code for common problems. e.g. the "math" module contains common math functions, the "urllib" module contains code to interact with urls and the web.

We say that you build your code "on top of" the module code. Modern coding is part custom code, and part building on top of module code.

import mathmath.sqrt(2)>>> import math >>> math.sqrt(2) # call sqrt() fn 1.4142135623730951 >>> math.sqrt <built-in function sqrt> >>> >>> math.log(10) 2.302585092994046 >>> math.pi # constants in module too 3.141592653589793

It's easy to forget the import line up at the top, but it's easy to fix

when you see the error.

The line import math, defines the symbol math to point to the module of code. If the import line is missing,

the error message will be about math not being defined.

Quit and restart the interpreter without the import, see common error:

>>> math.sqrt(2) # OOPS forgot the import Traceback (most recent call last): NameError: name 'math' is not defined >>> >>> import math >>> math.sqrt(2) # now it works 1.4142135623730951

Other modules are valuable but they are not a standard part of Python. For code using non-standard module to work, the module must be installed on that computer via the "pip" Python tool. e.g. for homeworks we had you pip-install the "Pillow" module with this command:

$ python3 -m pip install Pillow ..prints stuff... Successfully installed Pillow-5.4.1

A non-standard module can be great, although the risk is harder to measure. The history thus far is that popular modules continue to be maintained. Sometimes the maintenance is picked up by a different group than the original module author. A little used module is more risky.

When you upgrade Python, from 3.11 to to 3.12, you will lose the pip installed modules which are back in your previous Python 3.11 directories. You need to re-install your pop modules - not hard actually.

requirements.txt FeatureWe're not doing this in CS106A, just mentioning it. There's a pattern where you store a list of all the modules in a file "requirements.txt" and then "pip" can read this file and install them all in one step. You could use this to re-install all the modules you are using in one line.

Save a list of all our modules in a "requirements.txt" file — it records each module and the exact version installed, so later this set of installed modules can be reproduced exactly.

$ python3 -m pip freeze > requirements.txt $ cat requirements.txt asgiref==3.8.1 build==1.0.3 cachetools==5.3.1 certifi==2023.7.22 charset-normalizer==3.2.0 ...

The pip system can then install (or re-install) all the modules listed in a requirements.txt file in one step like this:

$ python3 -m pip install -r requirements.txt

When you install a module on your machine from somewhere - you are trusting that code to run on your machine. In very rare cases, bad actors have tampered with modules to include malware in the module, which then runs on your machine, steal data, install malware, etc. A so called "supply chain attack"

Installing code from python.org is very safe, and also very well known modules like Pillow and matplotlib are very safe, benefiting from large, active base of users.

Several supply chain attacks have been made on lesser known modules, from lesser known code sources, in particular the code source pypi.org. They are aware of this problem and are working on it. There are also "typosquatting" attacks, where bad guys put up a malware module with a name easily confused with the real module, something like a "matplotplib", expecting that some unwary people will install the bad one by accident.

Be more careful if installing a little used module. Prefer code that was released a month ago vs. code that was released yesterday, allowing time for the community to notice if something is not right.

dir() and help() (optional)>>> import math

>>> dir(math)

['__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'acos', 'acosh', 'asin', 'asinh', 'atan', 'atan2', 'atanh', 'ceil', 'copysign', 'cos', 'cosh', 'degrees', 'e', 'erf', 'erfc', 'exp', 'expm1', 'fabs', 'factorial', 'floor', 'fmod', 'frexp', 'fsum', 'gamma', 'gcd', 'hypot', 'inf', 'isclose', 'isfinite', 'isinf', 'isnan', 'ldexp', 'lgamma', 'log', 'log10', 'log1p', 'log2', 'modf', 'nan', 'pi', 'pow', 'radians', 'remainder', 'sin', 'sinh', 'sqrt', 'tan', 'tanh', 'tau', 'trunc']

>>>

>>> help(math.sqrt)

Help on built-in function sqrt in module math:

sqrt(x, /)

Return the square root of x.

>>>

>>> help(math.cos)

Help on built-in function cos in module math:

cos(x, /)

Return the cosine of x (measured in radians).

How hard is it to write a module? Not hard at all. A regular file like wordcount.py is also a module.

Consider the file wordcount.py in wordcount.zip

Forms a module named wordcount

Try this demo in the wordcount directory

>>> # Run interpreter in wordcount directory

>>> import wordcount

>>>

>>> wordcount.read_counts('poem.txt')

{'roses': 1, 'are': 2, 'red': 1, 'violets': 1, 'blue': 1, 'this': 1, 'does': 1, 'not': 1, 'rhyme': 1}

>>>

# 1. In the babygraphics.py file # import the babynames.py file in same directory import babynames ... # 2. Call the read_files() function names = babynames.read_files(FILENAMES)

>>> dir(wordcount)

['__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'clean', 'main', 'print_counts', 'print_top', 'read_counts', 'sys']

>>>

>>> help(wordcount.read_counts)

read_counts(filename)

Given filename, reads its text, splits it into words.

Returns a "counts" dict where each word

...

JSON is a standard for writing out as text all of the data that makes up a data structure, such that the data structure can be re-created from the text. It's a extremely popular, so you will likely come across it. JSON works across many different computer languages and systems. It is a safe interchange format. JSON is relatively simple, with just a few features and that's it. This is likely why it has become so popular. It solves a key problem well, and yet it's relatively simple.

In your future projects, the data formats you are most likely to see I would guess are (1) text files, and (2) json.

There is a standard Python module called json that reads and writes json data, and we'll show how to call its functions here.

Say you have a Python data structure in memory, such as a dictionary. To dump in JSON terminology means to write out the data structure into a big text string, suitable for saving to a file. The later, the load operation reads the JSON text, and re-creates the data structure.

Suppose I have this dictionary data in Python.

>>> d = {

'name': 'Hermione',

'nums': [1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

'safe': False,

'bugs': None,

'text': 'this is "easy"'

}

Import the json module and call json.dumps(d) — this returns a string that encodes the whole dictionary as text. (The "s" at the end of "dumps" refer to returning a "string" dump of the data.) The JSON encoding looks very similar to Python regular syntax, but it has little differences. Note that the last bit of text has quote marks in it, so that will be a little challenging for JSON to encode.

IMPORTANT The key thing about the JSON encoding, is that the JSON system can read it back in to re-create the data structure exactly. Once we trust that, the details of how JSON encodes things are just details.

The JSON encoded format is similar to a Python literal. It uses square brackets, curly braces, colons and commas all in ways similar to Python, but with a few differences:

1. It uses double quote marks for all strings, not a mix of single and double quote marks like we use in Python.

2. It uses backslashes inside each string to encode special chars in the string, so a double quote mark in a string is encoded as \". The JSON reading code then un-does the backslashes to get the original text back.

3. The Python boolean values are encoded with lowercase letters: true/false

4. The Python None is encoded as null

Here's the encoded form of above. The big change is that everything uses double quote marks, and we see the backslash is used for the last string. (Here I've separated the items on separate lines for readability, but JSON actually just separates them by spaces.)

>>> import json

>>>

>>> json_str = json.dumps(d) # dump out above dict

>>> print(json_str) # produces json text below

{

"name": "Hermione",

"nums": [1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

"safe": false,

"bugs": null,

"text": "this is \"easy\""

}

In JSON a load operation then goes the other direction, reading in JSON text and re-creating the original data structure in memory. The json.loads(s) function takes in a string of JSON data as a parameter.

# have json_str from above # (I've inserted newlines in the output for clarity) >>> json.loads(json_str) { 'name': 'Hermione', 'nums': [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], 'safe': False, 'bugs': None, 'text': 'this is "easy"' }

The JSON load operation re-creates the original dictionary perfectly. Note that the booleans and the null have been converted back to Python form, and the double quotes are maintained inside the last string.

If a file contains JSON text, then it is best to let the json module read the text out of the file itself. The json.load(f) function takes in the file-handle parameter and then does the reading of the text (here there is no "s" at the end of the json.load(f), as this is the file variant, not the string variant):

# filename is the name of a file with JSON # text in it we want to read # 1. Use with/open, similar to reading lines with open(filename) as f: d = json.load(f) # 2. Or can do it this way, placing the open() # right inside the load() d = json.load(open(filename))

1. dump - dump out a data structure as JSON text, suitable for saving in a file or writing on the network.

>>> # d is some data structure >>> json_str = json.dumps(d)

2. load - reads in JSON text and re-creates the original data structure in memory. The JSON text can be in a string, or can be read from a file, as in this example:

>>> with open(filename) as f:

d = json.load(f)

>>>

This is also a module story - there's some complexity about how to properly dump out and read back in JSON text. And all that detail is solved for us in the dump() and load() functions, and we are happy to just call them and let the module deal with the details.

Suppose we have this text on screen

This important text

Here is the HTML code to produce the above, with tags like <b> inserted in the text to indicate bold, paragraphs, urls etc. etc. sprinkled in the text..

This <b>important</b> textHTML Experiment - View Source

Go to python.org. Try view-source command on this page (right click on page). Search for a word in the page text, such as "whether" .. to find that text in the HTML code.

Think of how many web pages you have looked at - this is the code behind those pages. It's a text format! Lines of unicode chars!

Every web page you've ever seen is defined by this HTML text behind the scenes. Hmm. Python is good at working with text.

(See copy of these lines below suitable for copy/paste yourself.)

>>> import urllib.request

>>> f = urllib.request.urlopen('http://www.python.org/')

>>> text = f.read().decode('utf-8')

>>> text.find('Whether')

26997

>>> text[26997:27100]

"Whether you're new to programming or an experienced developer, it's easy to learn and use Python"

Here is the above Python lines, suitable for copy paste:

import urllib.request

f = urllib.request.urlopen('http://www.python.org/')

text = f.read().decode('utf-8')

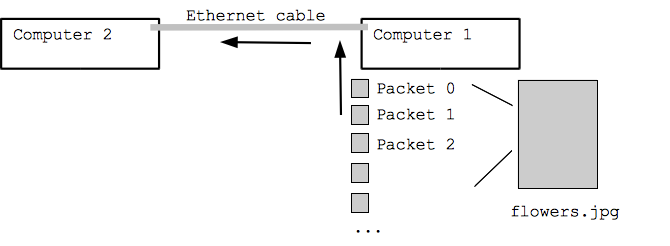

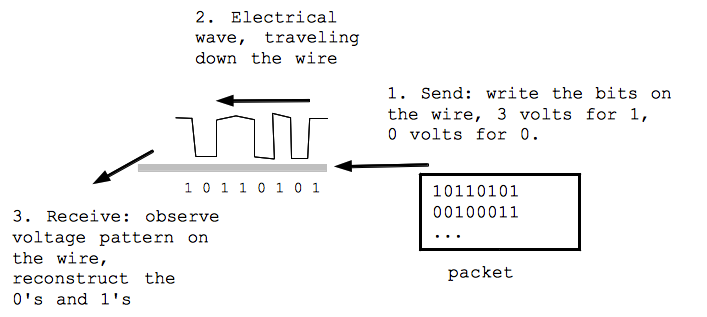

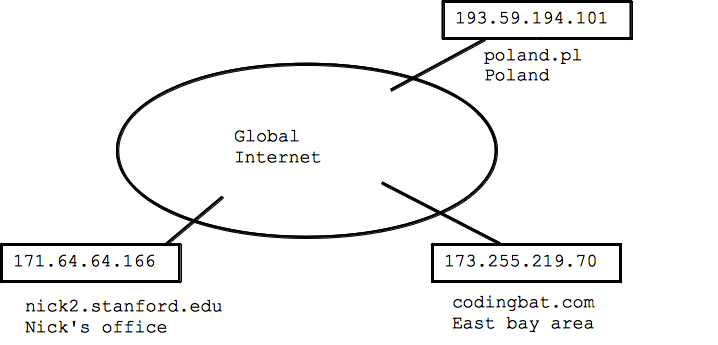

Just for fun, how does the Internet work? I pulled these slides together I had laying around from another class. Neat to see how something you use every day works.

TCP/IP blooper in this video of "The Net"...

Blooper: in the video the IP address is shown as 75.748.86.91 - not a valid IP address! Each number should be 1 byte, 0..255

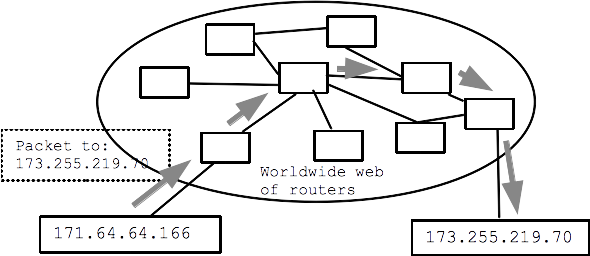

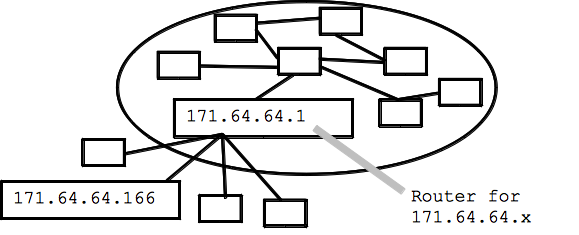

The most common way for a computer to be "on the internet" is to establish a connection with a "router" which is already on the internet. The computer establishes a connection via, say, wifi to communicate packets with the router. The router is "upstream" of the computer, connecting the computer to the whole internet.

The packet is passed from router to router - called a "hop". There might be 10 or 20 hops in a typical internet connection.

The routing of a packet from your computer is like a capillary/artery system .. your computer is down at the capillary level, your packet gets forwarded up to larger and larger arteries, makes its way over to the right area, and then down to smaller and smaller capillaries again, finally arriving at its destination.

Open the networking control panel on your computer / phone. Look for (1) your ip address, (2) the ip address of your router, (3) the DHCP option is typically enabled.

"Ping" is an old and very simple internet utility. Your computer sends a "ping" packet to any computer on the internet, and the computer responds with a "ping" reply (most but not all computers respond to ping). In this way, you can check if the other computer is functioning and if the network path between you and it works. As a verb, "ping" is also used in regular English this way .. not sure if that's from the internet or the other way around.

Experiment: Most computers have a ping utility, or you can try "ping" on the command line (works on the Mac, Windows, and Linux). Try pinging www.google.com or pippy.stanford.edu. Not all computers respond to ping. Type ctrl-c to terminate ping.

Milliseconds fraction of a second used for the packet to go and come back. 1 ms = 1/1000 of a second. Different from bandwidth, this "round trip delay".

Here I run the "ping" program for a few addresses, see what it reports. Every second, a ping packet is sent and the result is printed.

$ ping www.google.com # I type in a command here PING www.l.google.com (74.125.224.144): 56 data bytes 64 bytes from 74.125.224.144: icmp_seq=0 ttl=53 time=8.219 ms 64 bytes from 74.125.224.144: icmp_seq=1 ttl=53 time=5.657 ms 64 bytes from 74.125.224.144: icmp_seq=2 ttl=53 time=5.825 ms ^C # Type ctrl-C to exit --- www.l.google.com ping statistics --- 3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0.0% packet loss round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 5.657/6.567/8.219/1.170 ms $ ping pippy.stanford.edu PING pippy.stanford.edu (171.64.64.28): 56 data bytes 64 bytes from 171.64.64.28: icmp_seq=0 ttl=64 time=0.686 ms 64 bytes from 171.64.64.28: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.640 ms 64 bytes from 171.64.64.28: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.445 ms 64 bytes from 171.64.64.28: icmp_seq=3 ttl=64 time=0.498 ms ^C --- pippy.stanford.edu ping statistics --- 4 packets transmitted, 4 packets received, 0.0% packet loss round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 0.445/0.567/0.686/0.099 ms

Traceroute is a program that will attempt to identify all the routers in between you and some other computer out on the internet - demonstrating the hop-hop-hop quality of the internet. Most computers have some sort of "traceroute" utility available if you want to try it yourself (not required). On Windows it's called "tracert" in Windows Power Shell, and it does not support the "-q 1" option below, but otherwise works fine.

Some routers are visible to traceroute and some not, so it does not provide completely reliable output. However, it is a neat reflection of the hop-hop-hop quality of the internet.

codingbat.com is housed in the east bay - 13 hops we see here. The milliseconds listed is the round-trip delay to that router.

$ traceroute -q 1 codingbat.com traceroute to codingbat.com (173.255.219.70), 64 hops max, 52 byte packets 1 rt-ac68u-b3f0 (192.168.1.1) 7.152 ms 2 96.120.89.177 (96.120.89.177) 9.316 ms 3 24.124.159.189 (24.124.159.189) 9.638 ms 4 be-232-rar01.santaclara.ca.sfba.comcast.net (162.151.78.253) 9.775 ms 5 be-39931-cs03.sunnyvale.ca.ibone.comcast.net (96.110.41.121) 31.753 ms 6 be-3202-pe02.529bryant.ca.ibone.comcast.net (96.110.41.214) 10.273 ms 7 ix-xe-0-1-1-0.tcore1.pdi-paloalto.as6453.net (66.198.127.33) 10.570 ms 8 if-ae-2-2.tcore2.pdi-paloalto.as6453.net (66.198.127.2) 11.344 ms 9 if-ae-5-2.tcore2.sqn-sanjose.as6453.net (64.86.21.1) 13.555 ms 10 if-ae-1-2.tcore1.sqn-sanjose.as6453.net (63.243.205.1) 11.583 ms 11 216.6.33.114 (216.6.33.114) 11.938 ms 12 if-2-4.csw6-fnc1.linode.com (173.230.159.87) 14.833 ms 13 li229-70.members.linode.com (173.255.219.70) 11.549 ms

A random Serbian address - 31 hops - the farthest thing I could fine. See the extra delay where the packets go across the Atlantic - I'm guessing hop 16. The names there may refer to Amsterdam and France. Note that the packets are going at a fraction of the speed of light here - a fundamental limit of how quickly you can get a packet across the earth.

Or try: www.fu-berlin.de or www.parlament.hu or be1.rtr1.vh.hbone.hu

May hang at the end, but we can at least see the early hops.

$ traceroute -q 1 yujor.fon.bg.ac.rs traceroute to hostweb.fon.bg.ac.rs (147.91.128.13), 64 hops max, 52 byte packets 1 rt-ac68u-b3f0 (192.168.1.1) 9.136 ms 2 96.120.89.177 (96.120.89.177) 9.608 ms 3 24.124.159.189 (24.124.159.189) 20.184 ms 4 be-232-rar01.santaclara.ca.sfba.comcast.net (162.151.78.253) 15.058 ms 5 be-39911-cs01.sunnyvale.ca.ibone.comcast.net (96.110.41.113) 11.050 ms 6 be-3411-pe11.529bryant.ca.ibone.comcast.net (96.110.33.94) 11.294 ms 7 be3111.ccr31.sjc04.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.11.5) 10.420 ms 8 be2379.ccr21.sfo01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.42.157) 20.021 ms 9 be3110.ccr32.slc01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.44.142) 37.200 ms 10 be3037.ccr21.den01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.41.146) 36.318 ms 11 be3035.ccr21.mci01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.5.90) 49.991 ms 12 be2831.ccr41.ord01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.42.166) 66.591 ms 13 be2718.ccr22.cle04.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.7.130) 67.178 ms 14 be2993.ccr31.yyz02.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.31.226) 77.369 ms 15 be3260.ccr22.ymq01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.42.90) 86.026 ms 16 be3042.ccr21.lpl01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.44.161) 152.559 ms 17 be2183.ccr42.ams03.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.58.70) 161.324 ms 18 be2813.ccr41.fra03.atlas.cogentco.com (130.117.0.122) 164.945 ms 19 be2960.ccr22.muc03.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.36.254) 172.507 ms 20 be2974.ccr51.vie01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.58.6) 197.670 ms 21 be3463.ccr22.bts01.atlas.cogentco.com (154.54.59.186) 181.075 ms 22 be3261.ccr31.bud01.atlas.cogentco.com (130.117.3.138) 184.336 ms 23 be2246.rcr51.b020664-1.bud01.atlas.cogentco.com (130.117.1.14) 189.231 ms 24 149.6.182.114 (149.6.182.114) 182.364 ms 25 amres-ias-amres-gw.bud.hu.geant.net (83.97.88.6) 191.607 ms 26 amres-mpls-core----amres-ip-core-amres-ip.amres.ac.rs (147.91.5.144) 187.181 ms 27 * 28 stanica-134-241.fon.bg.ac.rs (147.91.134.241) 204.945 ms 29 stanica-134-250.fon.bg.ac.rs (147.91.134.250) 192.673 ms 30 stanica-134-250.fon.bg.ac.rs (147.91.134.250) 193.978 ms 31 stanica-134-250.fon.bg.ac.rs (147.91.134.250) 193.032 ms !Z