cat with empty chip bag

cat with empty chip bag

Today: nesting, new data type dict and the dict-count algorithm, something extra at end

dict - Hash Table - FastFor more details sees the chapter in the Guide: Dict

Suppose you come home and this is the situation:

cat with empty chip bag

cat with empty chip bag

Visualize the check-out at Trader Joes. You hear "beep" "beep" as the barcode for each item is scanned. Each item's barcode holds a UPC code string, like '0061-4207'. The register needs to lookup the current price for each item.

The price data is stored in a dictionary. There is a key for each UPC code. Each key has an associated value stored in the dictionary, and in this case the value is the current price for each UPC. Each time the register looks up another UPC key to the price, it makes a little beep.

The superpower of the dict is lookup — given a UPC code string, e.g. '0061-4207', lookup the value stored in the dict for that key instantly, in this case 4.99. It makes no difference if the UPC code is the first or last in the dict, the lookup of the UPC key is basically instant.

>>> d = {} # Start with empty dict {}

>>> d['a'] = 'alpha' # Set key/value

>>> d['g'] = 'gamma'

>>> d['b'] = 'beta'

>>> # Now we have built the picture above

>>> # Python can input/output a dict using

>>> # the literal { .. } syntax.

>>> d

{'a': 'alpha', 'g': 'gamma', 'b': 'beta'}

>>>

>>> s = d['g'] # Get by key

>>> s

'gamma'

>>> d['b']

'beta'

>>> d['a'] = 'apple' # Overwrite 'a' key

>>> d['a']

'apple'

>>>

>>> # += modify str value

>>> d['a'] += '!!!'

>>> d['a']

'apple!!!'

>>>

>>> d

{'a': 'apple!!!', 'g': 'gamma', 'b': 'beta'}

>>>

>>> # Can initialize dict with literal

>>> d = {'a': 'alpha', 'g': 'gamma', 'b': 'beta'}

>>>

>>> val = d['x'] # Key not in -> Error

Error:KeyError('x',)

>>>

>>> 'a' in d # "in" key tests

True

>>> 'x' in d

False

>>>

>>> # "in" logic before square bracket

>>> if 'x' in d:

val = d['x']

>>>

The get/set/in logic of the dict is always by key. The key for each key/value pair is how it is set and found. The value is actually just stored without being looked at, just so it can be retrieved later. In particular get/set/in logic does not use the value. See the last line below.

>>> d = {'a': 'alpha', 'g': 'gamma', 'b': 'beta'}

>>>

>>> d['a'] # key works

'alpha'

>>> 'g' in d

True

>>>

>>> 'gamma' in d # value doesn't work

False

>>>

The dictionary is like memory - put something in, later can retrieve it.

Problems below use a "meals" dict to remember what food was eaten under the keys 'breakfast', 'lunch', 'dinner'.

>>> meals = {}

>>> meals['breakfast'] = 'apple'

>>> meals['lunch'] = 'donut'

>>>

>>> # time passes, other lines run

>>>

>>> # what was lunch again?

>>> meals['lunch']

'donut'

>>>

>>> # did I have breakfast and dinner yet?

>>> 'breakfast' in meals

True

>>> 'dinner' in meals

False

>>>

Look at the dict1 "meals" exercises on the experimental server

> dict1 meals exercises

With the "meals" examples, the keys are 'breakfast', 'lunch', 'dinner' and the values are like 'hot dot' and 'bagel'. A key like 'breakfast' may or may not be in the dict, so need to "in" check first. No loops in these.

dict[key]Often we want to pull a value out for a particular key:

# Want - something like this

val = d[key]

But there is always the risk — what if that key is not in the dict? In that case, trying to read d[key] will crash with KeyError. Therefore, the code often has an "in" check about that key before trying to read that key .

# Write it this way

if key in d:

val = d[key]

early_apple(meals): Return True if 'breakfast' or 'lunch' is 'apple', and False otherwise.

def early_apple(meals):

if 'breakfast' in meals:

if meals['breakfast'] == 'apple':

return True

if 'lunch' in meals:

if meals['lunch'] == 'apple':

return True

# Could use "and" instead of nested "if"

return False

More practice:

bad_start(meals): Return True if there is no 'breakfast' key in meals, or the value for 'breakfast' is 'candy'. Otherwise return False.

> enkale()

enkale(meals): If the key 'dinner' is in the dict with the value 'candy', change the value to 'kale'. Otherwise leave the dict unchanged. Return the dict in all cases.

Demo: work out the code, see key error

Cannot access meals['dinner'] in the case that dinner is not in the dict, so need logic to avoid that case.

def enkale(meals):

if 'dinner' in meals:

if meals['dinner'] == 'candy':

meals['dinner'] = 'kale'

return meals

Instead of nested-if, could write it with "and" (either way of writing it is fine):

def enkale(meals):

if 'dinner' in meals and meals['dinner'] == 'candy':

meals['dinner'] = 'kale'

return meals

This is the "guard" pattern again — the "in" check guards the meals['dinner'] access, since the and/short-circuit goes left-to-right, and stops on a False.

is_boring(meals): Given a "meals" dict. We'll say the meals dict is boring if lunch and dinner are both present and are the same food. Return True if the meals dict is boring, False otherwise.

Idea: could solve without worrying about the KeyError first. Then put in the needed "in" guard checks.

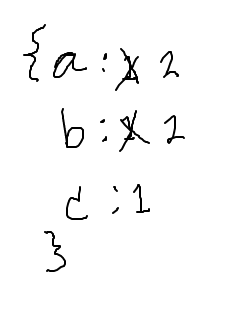

Example input strings:

['a', 'b', 'a', 'c', 'b']

Compute counts:

{'a': 2, 'b': 2, 'c': 1}

> dict2 Count exercises

Do the following for each s in strs. At the end, counts dict is built.

Go through these strs strs = ['a', 'b', 'a', 'c', 'b']Sketch out counts dict here:

Counts dict ends up as {'a': 2, 'b': 2, 'c': 1}:

str_count1 demo, canonical dict-count algorithm

def str_count1(strs):

counts = {}

for s in strs:

# s not seen before?

if s not in counts:

counts[s] = 1 # first time

else:

counts[s] +=1 # every later time

return counts

def str_count2(strs):

counts = {}

for s in strs:

# fix counts/s if not seen before

if s not in counts:

counts[s] = 0

# Unified: now s is in counts one way or

# another, so this works for all cases:

counts[s] += 1

return counts

Apply the dict-count algorithm to a list of int values, return a counts dict, counting how many times each int value appears in the list.

May get to this one, or students do on their own.

Apply the dict-count algorithm to chars in a string. Build a counts dict of how many times each char, converted to lowercase, appears in a string so 'Coffee' returns {'c': 1, 'o': 1, 'f': 2, 'e': 2}.