Today: exam prep, hardware tour, string functions, unicode

See course page for timing, logistics, lots of practice problems. Finish Crypto program, first, take a couple days off, then put in some time on practice problems for the exam, say starting by Sunday evening.

Topics on the exam: simple Bit (hw1), images/pixels/nested-loops (hw2), 2-d grids (hw3), strings, loops, simple lists (hw4)

Topics not on exam: bluescreen algorithm, writing main(), file reading

The bad news / good news of it

You have one on your person all day. You're debugging code for one. You see the output of them constantly. What is it and how does it work?

There are different types of CPU: x86, Arm, and more recently Risc-V. Low-level software created for one will not run on another. (Python is portable - your Python code will work without modification on many different CPUs). The x86 processors are associated with Intel and AMD and have had a long dominance dating back to the creation of the PC which used an x86 processor in 1982. More recently Arm licenses processors which are totally dominant in cell phones, and more recently Apple has used them in computers. Arm chips are a more modern design compared to x86. Most recently, Risc-v is a open/royalty-free type of CPU, where a manufacturer has the freedom to make them without permission (Arm and x86 are quite the opposite.) I would not be surprised to see Risc-V grow in importance, as openness has a long history of bringing in a lot of investment and creativity.

Want to talk about running a computer program...

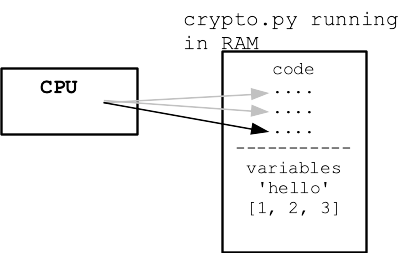

For example, we have cat.py - a python program. When not running, it is just a file sitting in storage (a file which you wrote!). To run the cat.py program, a "process" is created with space in RAM, and the CPU runs it there. When the program exits, the process is destroyed and the space in RAM can be used for something else.

Python allows us to write code to solve the problems we want without needing to know the details of the CPU and RAM. This is progress, much as its useful to be able to ride a bicycle without knowing the details of, say, its wheel bearings. That said, here we will look at how CPU and RAM are used to get a feel for the whole picture.

Nick's Hardware Squandering Program!

Demo: computer is mostly idle to start. An idle CPU does not create much heat. When the CPU starts running hard, it generates heat, and often the laptop fan will start running to cool the CPU. This program is an infinite loop, see the code below. It uses 100% of one core. If the fan running is running on your laptop, use Activity Monitor (Mac), Task Manager (Windows) to see what programs are running, see CPU% and MEM%.

Core function of -cpu feature:

def use_cpu(n):

"""

Infinite loop counting a variable 0, 1, 2...

print a line every n (0 = no printing)

"""

i = 0

while True:

if n != 0 and i % n == 0:

print(i)

i = i + 1

Try 1000 first ... yikes! Try 1 million instead. Type ctrl-c in the terminal to kill the process.

$ python3 hardware-demo.py -cpu 1000000 0 1000000 2000000 3000000 4000000 5000000 6000000 7000000 ^CTraceback (most recent call last): File "hardware-demo.py", line 66, inmain() File "hardware-demo.py", line 56, in main use_cpu(n) File "hardware-demo.py", line 24, in use_cpu i = i + 1 KeyboardInterrupt (Type ctrl-c to exit - ancient CS keystroke to terminate a process)

Demo: Nick opens a second terminal. This needs to be done outside of PyCharm - see the Command Line chapter. Run a second copy of hardware-demo.py. Look in the process manager .. now see two programs running at once.

When code reads and writes values, those values are stored in RAM. RAM is a big array of bytes, read and written by the CPU.

Say we have this code

n = 10 s = 'Hello' lst = [1, 2, 3] lst2 = lst

Every value in use by the program takes up space in RAM.

Demo using -mem, Look in activity monitor (task manager), "mem" area, 100 = 100 MB per second. Watch our program use more and more memory of the machine. Program exits .. not in the list any more! Fancy: try killing off the process from inside the process manager window.

$ python3 hardware-demo.py -mem 100 Memory MB: 100 Memory MB: 200 Memory MB: 300 Memory MB: 400 Memory MB: 500 Memory MB: 600 Memory MB: 700 ^CTraceback (most recent call last): ... KeyboardInterrupt (ctrl-c to exit)

See guide for details: Strings

Thus far we have done String 1.0: len, index numbers, [ ], in, upper, lower, isalpha, isdigit, slices, .find().

There are more functions. You should at least have an idea that these exist, so you can look them up if needed. The important strategy is: don't write code manually to do something a built-in function in Python will do for you. The most important functions you should have memorized, and the more rare ones you can look up.

These are very convenient True/False tests for the specific case of checking if a substring appears at the start or end of a string. Also a pretty nice example of function naming.

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Py')

True

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Px')

False

>>> 'resume.html'.endswith('.html')

True

Returns a version of the string with the "space" chars removed from its beginning and end. Use in the file-processing loop to remove the newline char '\n', like this:

>>> line = ' this and that\n' >>> line = line.strip() >>> line 'this and that'

>>> # Say read a line like this from file

>>> line = 'Smith,Astrid,112453,2022'

>>> parts = line.split(',')

>>> parts

['Smith', 'Astrid', '112453', '2022'] # split into parts

>>> parts[0]

'Smith'

>>> parts[2]

'112453'

>>>

>>> 'apple:banana:donut'.split(':')

['apple', 'banana', 'donut']

>>>

>>> 'this is it\n'.split() # special whitespace form

['this', 'is', 'it']

Say I have name and score variables and I want to put together a string with them. Use + and the str() function, like this:

>>> name = 'Alice' >>> score = 12 >>> name + ' got score:' + str(score) 'Alice got score:12' >>>

BUT there's a neat, new way to accomplish this..

Put a lowercase 'f' to the left of the string literal, making a specially treated "format" string. For each curly bracket {..} in the string, Python evaluates the expression within and pastes the resulting value into the string. Super handy! The expression has access to local variables, and can call functions. We do not need to call str() to convert to string, it's done automatically.

>>> name = 'Alice'

>>>

>>> f'this is {name}' # Variables work

'this is Alice'

>>>

>>> f'this is {name.upper()}' # Functions work

'this is ALICE'

>>>

>>> score = 12

>>> f'{name} got score:{score}'

Alice got score:12

>>>

{x:.4}Add ':.4' after the value in the curly braces to limit decimal digits printed. There are many other "format options", but this is the one I use the most by far.

>>> x = 2/3

>>> f'value: {x}'

'value: 0.6666666666666666'

>>> f'value: {x:.4}'

'value: 0.6667'

In the early days of computers, the ASCII character encoding was very common, encoding the roman a-z alphabet. ASCII is simple, and requires just 1 byte to store 1 character, but it has no ability to represent characters of other languages.

Each character in a Python string is a unicode character, so characters for all languages are supported. Also, many emoji have been added to unicode as a sort of character.

Every unicode character is defined by a unicode "code point" which is basically a big int value that uniquely identifies that character. Unicode characters can be written using the "hex" version of their code point, e.g. "03A3" is the "Sigma" char Σ, and "2665" is the heart emoji char ♥.

Hexadecimal aside: hexadecimal is a way of writing an int in base-16 using the digits 0-9 plus the letters A-F, like this: 7F9A or 7f9a. Two hex digits together like 9A or FF represent the value stored in one byte, so hex is a traditional easy way to write out the value of a byte. When you look up an emoji on the web, typically you will see the code point written out in hex, like 1F644, the eye-roll emoji 🙄.

You can write a unicode char out in a Python string with a \u followed by the 4 hex digits of its code point. Notice how each unicode char is just one more character in the string:

>>> s = 'hi \u03A3' >>> s 'hi Σ' >>> len(s) 4 >>> s[0] 'h' >>> s[3] 'Σ' >>> >>> s = '\u03A9' # upper case omega >>> s 'Ω' >>> s.lower() # compute lowercase 'ω' >>> s.isalpha() # isalpha() knows about unicode True >>> >>> 'I \u2665' 'I ♥'

For a code point with more than 4-hex-digits, use \U (uppercase U) followed by 8 digits with leading 0's as needed, like the fire emoji 1F525, and the inevitable 1F4A9.

>>> a = 'the place is on \U0001F525' >>> b = 'oh \U0001F4A9' >>> len(b) 4

The history of ASCII and Unicode is an example of ethics.

One byte per char, but only a-z roman alphabet. Not so helpful for non English speaking world.

In the early days of computing in the US, computers were designed with the ASCII character set, supporting only the roman a-z alphabet. This hurt the rest of the planet, which mostly doesn't write in English. There is a well known pattern where technology comes first in the developed world, is scaled up and becomes inexpensive, and then proliferates to the developing world. Computers in the US using ASCII hurt that technology pipeline. Choosing a US-only solution was the cheapest choice for the US in the moment, but made the technology hard to access for most of the world. This choice is somewhere between ungenerous and unethical.

Unicode takes 2-4 bytes per char, so it is more costly than ASCII.

Cost per byte aside, Unicode is a good solution - a freely available standard. If a system uses Unicode, it and its data can interoperate with the other Unicode compliant systems.

The cost of supporting non-ASCII data can be related to the cost of the RAM to store the unicode characters. In the 1950's every byte was literally expensive. An IBM model 360 could be leased for $5,000 per month, non inflation adjusted, and had about 32 kilobytes of RAM (not megabytes or gigabytes .. kilobytes!). So doing very approximate math, figuring RAM is half the cost of the computer, we get a cost of about $1 per byte per year.

>>> 5000 * 12 / (2 * 32000) 0.9375

So in 1950, Unicode is a non-starter. RAM is expensive.

What does the RAM in your phone cost today? Say the RAM cost of your phone is $500 and it has 8GB of RAM. What is the cost per byte?

The figure 8 GB is 8 billion bytes. In Python, you can write that as 8e9 - like on your scientific calculator.

>>> 500 / 8e9 # 8 GB 6.25e-08 >>> >>> 500 / 8e9 * 100 # in pennies 6.2499999999999995e-06

RAM costs nothing today - 6 millionths of a cent per byte. This is the result of Moore's law. Exponential growth is incredible.

Sometime in the 1990s, RAM was cheap enough that spending 2-4 bytes per char (unicode) was not so bad compared to 1 byte per char (ASCII). The Unicode standard was created around this time. Unicode is a standard way of encoding chars in bytes, so that all the Unicode systems can transparently exchange data with each other.

With Unicode, the tech leaders were showing a little generosity to all the non-ASCII computer users out there in the world.

With Unicode, there is a single Python language that can be used in every country - US, China, India, Netherlands.

A world of programmers contribute to Python as free, open source software. We all benefit from that community, vs. each country maintaining their own in-country programming language, which would be a crazy waste of duplicated effort.

So being generous is the right thing to do. But the story also shows, that when you are generous to the world, that generosity may well come around and help you as well.