Today: string in, if/elif, string .find(), slices and drawing

See chapters in Guide: String - If

in Test>>> 'Dog' in 'CatDogBird' True >>> 'dog' in 'CatDogBird' # upper vs. lower case False >>> 'd' in 'CatDogBird' # finds d at the end True >>> 'atD' in 'CatDogBird' # not picky about words True >>> >>> 'x' in 'CatDogBird' False

not inThere's also a not in form which is True if the element is not in there, similar to !=. Use this form an if-statement where you want to take an action if something is not in a string.

>>> s = 'CatDogBird'

>>> if 'Fish' not in s: # YES this way

print('no Fish')

no Fish

>>>

>>> if not 'Fish' in s: # NO works but not PEP8

print('no Fish')

no Fish

>>>

In Python style, the first form above - not in - is officially preferred to the second.

> has_pi()

'3.14' -> True

'a 14 b 3' -> True

'315' -> False

has_pi(s): Given a string s, return True if it contains the substrings '3' and '14' somewhere within it, but not necessarily together. Use "in".

Note these functions are in the string-3 section on the Experimental server

This looks reasonable.

if '3' and '14' in s:

...

Q: Does the above work?

A: No it does not work

This example looks sensible if we think of it as a phrase of English. So it is a bit tragic that it does not work in Python or most computer languages.

Unlike English text, the and must be between two boolean values, with each boolean value produced by an expression like < or == or in. The correct form is shown below. Notice how each side of the and is a free-standing expression that produces a boolean.

if '3' in s and '14' in s: # Works correctly

...

We prefer using Python built-in functions such as "in" vs. writing the code yourself. It would be a mistake to manually write code look through a string to see if another string appears in there. Just use "in" for that. The built-in works correctly, and it makes readable code, since Python programmers are already familiar with "in" and know what it does at a glance.

The "in" operator works for several data structure to see if a value is in there, and its use with strings is our first example of it. Also, in some cases, the built-in can run faster than what you could code yourself.

> catty()

'xaCtxyzAx' -> 'aCtA'

Return a string made of the chars from the original string, whenever the chars are one of 'c' 'a' 't', (not case sensitive).

Not case sensitive: convert each char to lowercase form with s[i].lower(), then do testing with the lowercase form.

This works correctly, but that if-test is quite long. Can we do better? Indeed, it's so long, it's awkward to fit on screen.

Aside: see style guide breaking up long lines for way to break up long lines like this.

def catty(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].lower() == 'c' or s[i].lower() == 'a' or s[i].lower() == 't':

result += s[i]

return result

> catty()

Start with the V1 code. Add a variable to hold the repeated computation — shorten the code and it "reads" better with the new variable.

low = s[i].lower()

Solution with "low" variable, better

def catty(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

low = s[i].lower() # Add var

if low == 'c' or low == 'a' or low == 't':

result += s[i]

return result

We will make frequent use of this strategy in CS106A. If the solution is getting a little lengthy, add a variable to hold some sub-part of the computation for use on later lines.

We'll talk about Style more later. For today, the name of a variable should label that value in the code, helping the programmer to keep their ideas straight. Other than that, being short is a great quality in a variable name. Typing and reading long variable names feels like a drag on the coding effort. The name does not need to repeat every true thing about the value. Just enough to distinguish it from other values in this algorithm.

1. Good names for this example, short but with key facts

# Good names

low

low_char

2. Names that are too long or too short:

# Too long low_char_i low_char_in_s # Too short, cryptic a c

3. Avoid this name: lower - the name would work, but we avoid choosing a name for a variable that is already the name of a function, to avoid confusion. Here .lower() is the name of a string function.

# Avoid Names of a Functions

lower

len

The V1 code above is acceptable, but V2 is shorter and nicer. The V2 code also runs slightly faster, as it does not needlessly re-compute the lowercase form three times per char.

This is just a coding trick, not something we would ever require or look for students to do. The way in works for strings, it can do the "or" logic for us, like this:

# This is fine if low == 'c' or low == 'a' or low == 't': ... # Trick: equivalent to the above if low in 'cat': ...

if and if/else:if/elifUse the if/elif structure to look through a series of tests, stopping at the first True test. The structure is exclusive; it selects one case and skips all the othres. This is much more rarely used than the plain if-statement.

The sequence is akin to looking through a series of drawers for a pen — you look in each drawer in turn, and stop as soon as you find the pen.

The structure has n if-tests.

if test1: action1 elif test2: action2 elif test3: action3 else: action4

Python goes through the tests from top to bottom, stopping at the first True test. Python runs the corresponding action, and then exits the if/elif structure. The result is that at most 1 of the n actions runs. An optional "else" at the end runs if none of the tests succeed. Mnemonic: the words "else" and "elif" are the same length.

The need for an if/elif structure is a little rare, but this problem is dialed in to show what if/elif solves.

The most common letters used in English text are: e, t, a, i, o, n

Here we process string s, swapping around the 3 most common vowels like this:

e -> a a -> i i -> e

This changes an English word in a way that looks like a word and is kind of funny.

'table' -> 'tibla' 'kitten' -> 'kettan' 'radio' -> 'rideo'

vowel_swap(s): Given string s. We'll swap around the three most common vowels in English, which are 'e', 'a', and 'i'. Return a form of s where each lowercase 'e' is changed to 'a', each 'a' is changed to 'i', and each 'i' is changed to 'e'. Other chars leave unchanged. So the word 'kitten' returns 'kettan'. The provided loop sets a variable ch to hold each char in turn, appending ch to the result. Add code to change ch.

The provided loop sets a variable ch to be each char in turn. This solution is written with plain "if" to check and change each char. Plain if works fine in many circumstances, but for this algorithm, it runs into a quite subtle problem.

def vowel_swap(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

ch = s[i]

# Make changes to ch

if ch == 'e':

ch = 'a'

if ch == 'a':

ch = 'i'

if ch == 'i':

ch = 'e'

result += ch

return result

Run this code. Here is some incorrect output it produces

'aaaa' -> 'eeee'

Why is 'a' replaced by 'e' instead of the expected 'i' here?

The problem is not obvious glancing at the code. Trace through the v1 code carefully for the input 'aaaa'. The ch == 'a' if-test succeeds, which is fine. But then the ch == 'i' test also succeeds, which is a problem. We have multiple if-tests, and they are interfering with each other.

With if/elif, only one if-test succeeds, which is what we want for this 'e' 'a' 'i' detection:

def vowel_swap(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

ch = s[i]

# Make changes to ch

if ch == 'e':

ch = 'a'

elif ch == 'a':

ch = 'i'

elif ch == 'i':

ch = 'e'

result += ch

return result

A return can accomplish exclusivity similar to the if/elif structure, which is why we have not really needed if/elif up until now. Suppose we are doing the vowel-swap algorithm, but in a function that processes a single char. This is our pick-off strategy, exiting the function once a solution is known.

def swap_ch(ch):

"""Vowel-swap on one char."""

if ch == 'e':

return 'a'

if ch == 'a':

return 'i'

if ch == 'i':

return 'e'

return ch

Since the return exits the function, we get in effect the if/elif behavior. Once an if-test succeeds, the later ones are skipped.

However, the full-string vowel_swap() above cannot use return like this, as it needs to keep running the loop to do the other characters. We need to handle each char in the loop but without leaving the function, and for that, the if/elif is perfect.

str_adx(s): Given string s. Return a string of the same length. For every alphabetic char in s, the result has an 'a', for every digit a 'd', and for every other type of char the result has an 'x'. So 'Hi4!x3' returns 'aadxad'. Use an if/elif structure.

>>> s = 'Python'

>>>

>>> s.find('th')

2

>>> s.find('o')

4

>>> s.find('y')

1

>>> s.find('x')

-1

>>> s.find('N')

-1

>>> s.find('P')

0

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[1:3] # 1 .. UBNI 'yt' >>> s[1:5] 'ytho' >>> s[4:5] 'o' >>> s[4:4] # Empty string ''

>>> s[:3] # Omit num = from/to end 'Pyt' >>> s[:4] 'Pyth' >>> s[4:] # Split str at 4 'on' >>> s[4:999] # Too big = through the end 'on' >>> s[:] # The whole thing 'Python'

This is a nice example. The code is dense, but we make a drawing and use it to guide the details in the lines of code. This code can easily fail with Off-By-One (OBO) errors, but we'll try to use the drawing to get each line exactly right. Or more simply — don't try to do it in your head.

> brackets

'cat[dog]bird' -> 'dog'

brackets(s): Look for a pair of brackets '[...]' within s, and return the text between the brackets, so the string 'cat[dog]bird' returns 'dog'. If there are no brackets, return None. If the brackets are present, there will be only one of each, and the right bracket will come after the left bracket.

A first venture into using index numbers and slices. Many problems work in this domain - e.g. extracting all the hashtags from your text messages.

![alt: draw 'cat[dog]bird', show left, right before arrows added](lecture-brackets.png)

![alt: draw 'cat[dog]bird', show left, right with arrows added pointing into string](lecture-brackets2.png)

def brackets(s):

left = s.find('[')

if left == -1:

return None

right = s.find(']')

return s[left + 1:right]

For programming style, we prefer "readable" code — when the eye sweeps over the code, what the code does is apparent. This code is quite dense, but the variable names do help. Look at the last line. You can see how it is using the index numbers for the left and right brackets, even if the OBO of the exact numbers is something puzzle over.

The variables left and right are a natural example of the Add Var strategy. Pulling important parts of the algorithm into variables, so the names of the variables sort of narrate the lines as you look at them.

Just as comparison, here's the code with no variables. It works fine, and it's one line shorter, but the readability is clearly worse. It also likely runs a little slower, as it computes the left-bracket index twice.

def brackets(s):

if s.find('[') == -1:

return None

return s[s.find('[') + 1:s.find(']')]

Code that is unreadable is more likely to have bugs, so we prefer the readable version, with its variables labeling the parts of the computation.

'hi((yo))bye' -> 'yo,yo,yo'

inside3x(s): Given a string that may contain a pair of double-parenthesis, like 'aa((bbb))cc'. There is some text inside the parenthesis and some before and after. Return a string like 'bbb,bbb,bbb', made of three copies of the inside text separated by commas. The string is guaranteed to either contain the double parenthesis in the correct order, or will contain no parenthesis. The starting code includes the two s.find() calls.

Hint: make a drawing. Pull out the text inside, store in a variable "text". Use + to put together the result string. Add an if-statement to pick off the case that there are no parenthesis. We cannot use "in" as a variable name, since it is a Python operator.

def inside3x(s):

left = s.find('((')

right = s.find('))')

if left == -1:

return None

text = s[left + 2:right] # Add var strategy

return text + ',' + text + ',' + text

> at_3

Here is a more difficult problem, similar to brackets for you to try. A drawing really helps the OBO on this one.

Milestone-1 - get the 'abc' output below, not worrying about if the input is too short

Milestone-2 - add logic for the too-short case. Note the i < len(s) valid idea below.

at_3(s): Given string s. Find the first '@' within s. Return the len-3 substring immediately following the '@'. Except, if there is no '@' or there are not 3 chars after the '@', return None.

'xx@abcd' -> 'abc' 'xxabcd' -> None 'x@x' -> None

i < len(s)More s.find() if we have time...

s.find() variant with 2 params: s.find(target, start_index) - start search at start_index vs. starting search at index 0. Returns -1 if not found, as usual. Use to search in the string starting at a particular index.

Suppose we have the string '[xyz['. How to find the second '[' which is at 4? Start the search at 1, just after the first bracket:

>>> s = '[xyz['

>>> s.find('[') # find first [

0

>>> s.find('[', 1) # start search at 1

4

> parens()

'x)x(abc)xxx' -> 'abc'

This is nice, realistic string problem with a little logic in it.

Thinking about this input: '))(abc)'.

Hint Here is some starting hint code, to find the right paren after the left paren:

left = s.find('(')

...

right = s.find(')', left)

1. This fine:right = s.find(')', left)

Is there a right parenthesis at index left? No, is not possible for a right parenthesis to be at that exact index. We already know that index holds a left parenthesis.

2. Therefore, could write it this way, moving the search for the right parenthesis 1 index farther along:right = s.find(')', left + 1)

We can appreciate having the sort of analytical mind that work out that (2) will work. That said, keeping things as simple as possible, KISS, is a great strategy for code, and so simply writing (1) is probably for the best.

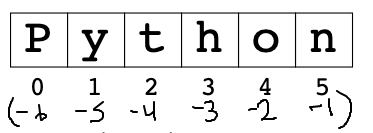

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[len(s) - 1] 'n' >>> s[-1] # -1 is the last char 'n' >>> s[-2] 'o' >>> s[-3] 'h' >>> s[1:-3] # works in slices too 'yt' >>> s[-3:] 'hon'