Python Classes

This week, we are going to start talking about classes and object oriented programming.

Slide 2

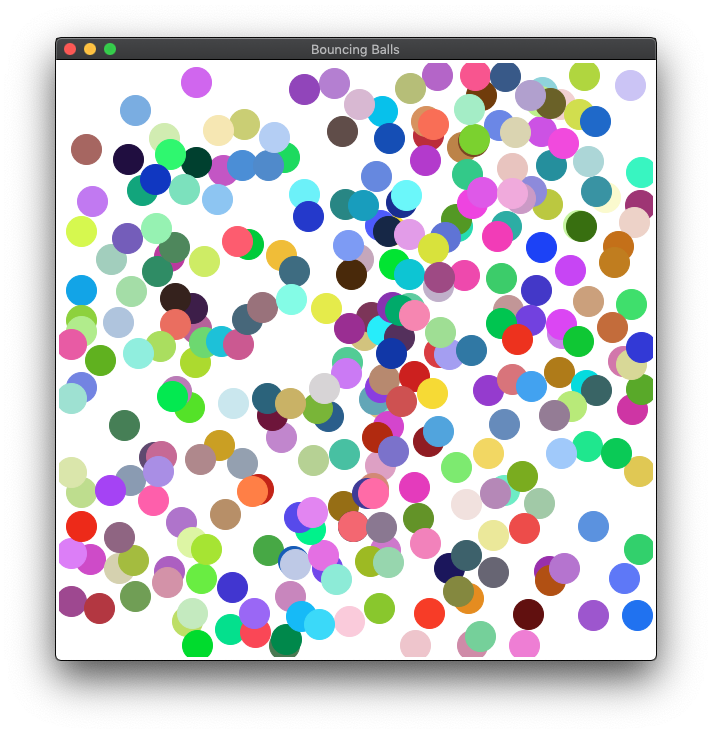

Demo: The Ball class

Slide 3

Object Oriented Programming uses classes to create objects that have the following properties:

- An object holds its own code and variables

- You can instantiate as many objects of a class as you'd like, and each one can run independently.

- You can have objects communicate with each other, but this is actually somewhat rare.

- The Ball class is an object

- You can create as many balls as you want

- Each can have its own attributes

- color

- direction

- size

- etc.

Slide 4

- When we create a new class, we actually create a new type. We have only used types that are built in to python so far: strings, ints, floats, dicts, lists, tuples, etc.

- Now, we are going to create our own type, which we can use in a way that is similar to the built-in types.

- Let's start with the Ball example, but let's make it a bit simpler than in the demo. In fact, let's make it really simple (in that it doesn't do anything):

class Ball:

"""

The Ball class defines a "ball" that can bounce around the screen

"""

In the REPL:

>>> class Ball:

... """

... The Ball class defines a "ball" that can bounce around the screen

... """

...

>>> print(Ball)

<class '__main__.Ball'>

>>>

Note that the full name for the ball type is __main__.Ball.

Slide 5

Once we have a class, we can create an instantiation of the class to create an object of the type of the class we created:

>>> class Ball:

... """

... The Ball class defines a "ball" that can bounce around the screen

... """

...

>>> print(Ball)

<class '__main__.Ball'>

>>>

>>> my_ball = Ball()

>>> print(my_ball)

<__main__.Ball object at 0x109b799e8>

>>>

Now we have a Ball instance called my_ball that we can use. We can create as many more instances as we'd like:

>>> lots_of_balls = [Ball() for x in range(1000)]

>>> len(lots_of_balls)

1000

>>> print(lots_of_balls[100])

<__main__.Ball object at 0x109dc6e10>

>>>

We now have 1000 instances of the Ball type in a list.

Slide 6

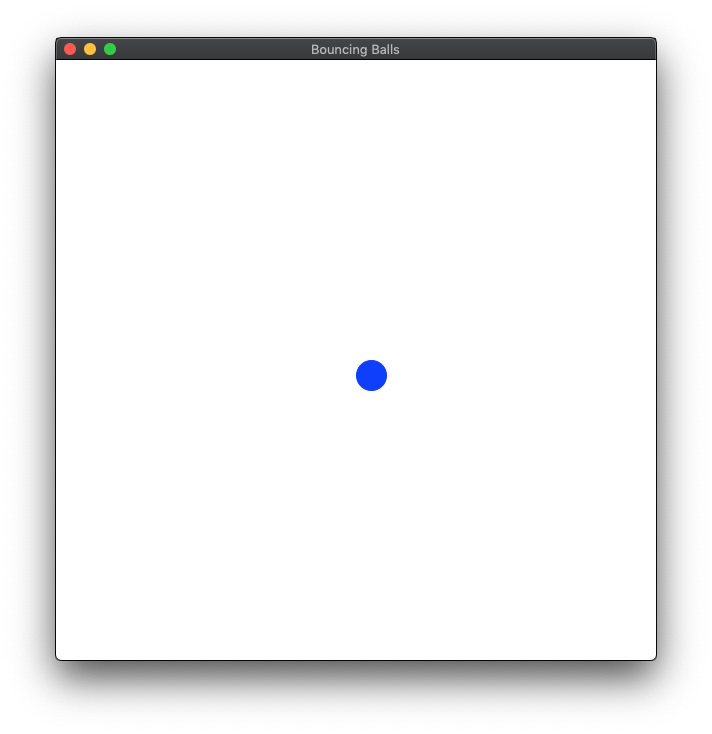

- Let's make our Ball a bit more interesting. Let's add a location for the Ball, and let's also make a method that draws the ball on a canvas, which is a drawing surface available to Python through the Tkinter GUI (Graphical User Interface)

- We can add functions to a class, too – they are called methods, and are run with the dot notation we are used to. There is a special method called

__init__that runs when we create a new class object:

class Ball:

"""

The Ball class defines a "ball" that can

bounce around the screen

"""

def __init__(self, canvas, x, y):

self.canvas = canvas

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.draw()

def draw(self):

width = 30

height = 30

outline = 'black'

fill = 'black'

self.canvas.create_oval(self.x, self.y,

self.x + width,

self.y + height,

outline=outline,

fill=fill)

The __init__ method is called immediately when we create an instance of the class. You can think of it as the setup, or initialization routine.

With classes, you'll see the keyword self a lot. Whenever there is a self, it means that the variable is referring to the instance variable of a particular object of the type (in our case, a Ball). Each object has its own copies of the self variables. So, if we created two different Balls, each would have its own self.x and self.y positions.

All class methods inherently have a hidden self parameter, as you can see from the definitions of __init__ and draw. You don't need to worry about passing in self, as it is handled by the class mechanics. For our purposes, __init__ has three parameters (even though it looks like it has four), and draw has zero parameters.

Notice in "draw" that we create regular variables. Those can only be used in the method itself.

If we want, we can promote those variables to become attributes so different instances can have different values.

Slide 7

class Ball:

"""

The Ball class defines a "ball" that can

bounce around the screen

"""

def __init__(self, canvas, x, y):

self.canvas = canvas

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.draw()

def draw(self):

width = 30

height = 30

outline = 'blue'

fill = 'blue'

self.canvas.create_oval(self.x, self.y,

self.x + width,

self.y + height,

outline=outline,

fill=fill)

def animate(playground):

canvas = playground.get_canvas()

ball = Ball(canvas, 10, 10)

canvas.update() // redraw canvas

Because Tkinter needs some setup, I haven't included it here. But, assume you have an animate function that has a playground parameter that gives you a canvas.

When we instantiate ball, the __init__ method is called, which sets up the attributes, and then draws the ball on the screen.

Slide 8

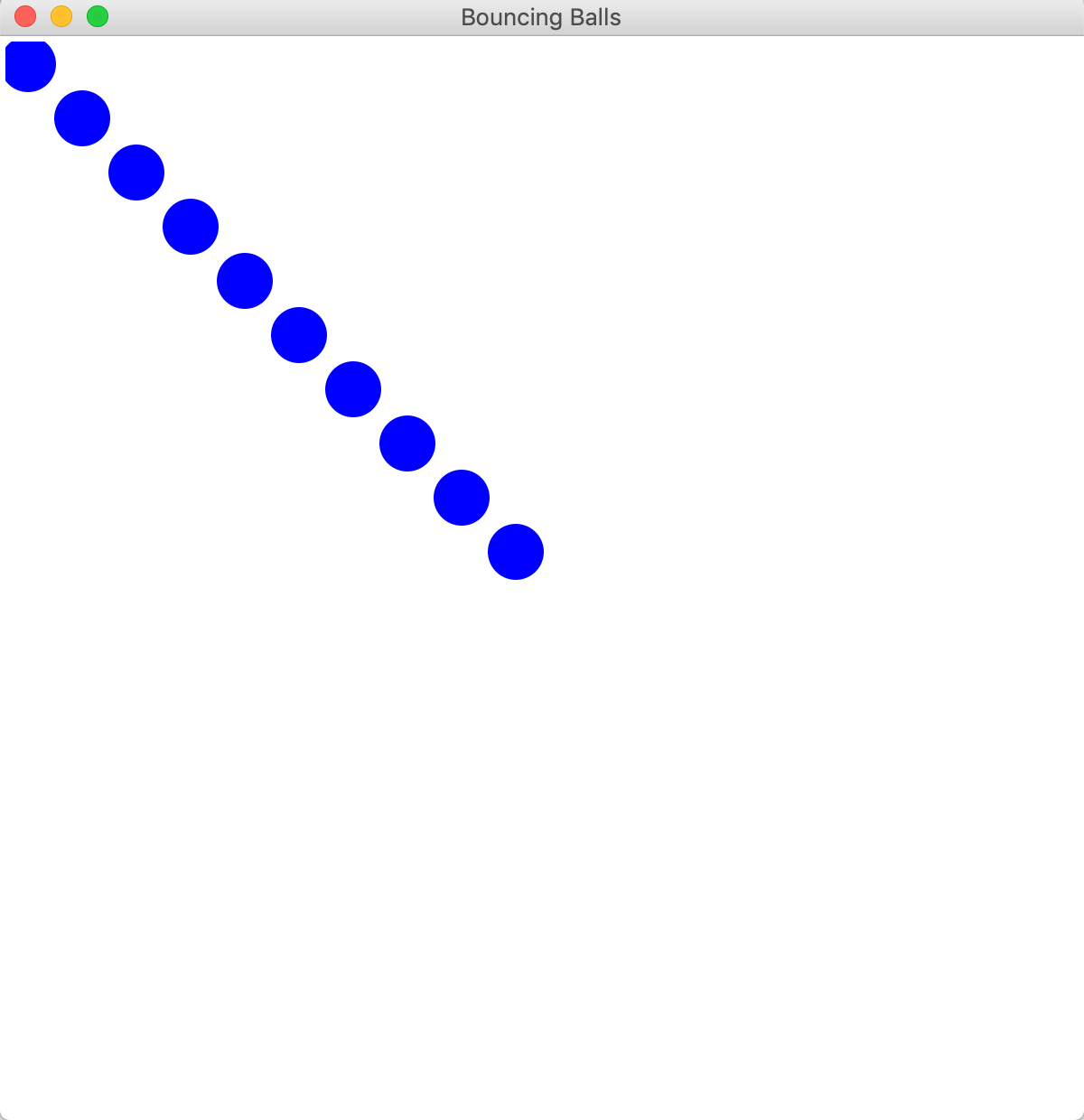

We could, of course, create as many balls as we'd like:

def animate(playground):

canvas = playground.get_canvas()

balls = []

for i in range(10)

balls.append(Ball(canvas, 30 * i, 30 * i))

canvas.update() // redraw canvas

Now, we can modify each of the ball's position, size, and color independently. What could we do if we wanted to give each attribute a default value? Just like with regular functions, the init method can accept defaults (see next slide)

def animate(playground):

canvas = playground.get_canvas()

ball1 = Ball(canvas, 100, 100, 50, 30, "magenta")

ball2 = Ball(canvas, 40, 240, 10, 100, "aquamarine")

ball3 = Ball(canvas, 200, 200, 150, 10, "goldenrod1")

ball4 = Ball(canvas, 300, 300, 1000, 1000, "yellow")

canvas.update()

Slide 9

class Ball:

"""

The Ball class defines a "ball" that can

bounce around the screen

"""

def __init__(self, canvas, x, y,

width=30, height=30, fill="blue"):

self.canvas = canvas

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.width = width

self.height = height

self.fill = fill

self.draw()

def draw(self):

self.canvas.create_oval(self.x, self.y,

self.x + self.width,

self.y + self.height,

outline=self.fill,

fill=self.fill)

def animate(playground):

canvas = playground.get_canvas()

ball1 = Ball(canvas, 100, 100) # default size and color

ball2 = Ball(canvas, 40, 240, fill="aquamarine")

ball3 = Ball(canvas, 200, 200, 150, 10)

ball4 = Ball(canvas, 300, 300, 1000, 1000, "yellow")

canvas.update()

The __str__ and __eq__ methods of a class

Besides init, there are a couple of other special methods that classes know about, and that you can write:

- str

- Returns a string that you can print out that tells you about the instance

- eq

- If you pass in two instances, eq will return True if they are the same, and False if they are different

- We can define these functions to do whatever we want, but we generally want them to make sense for creating a string representation of the object, and for determining if two objects are equal.

Slide 10

Before we write the functions, let's see what happens when we try to print a ball, and to determine if two balls are equal:

ball1 = Ball(canvas, 100, 100) # default size and color

ball2 = Ball(canvas, 40, 240, fill="aquamarine")

ball3 = Ball(canvas, 200, 200, 150, 10)

ball4 = Ball(canvas, 300, 300, 1000, 1000, "yellow")

ball5 = Ball(canvas, 300, 300, 1000, 1000, "yellow") // same as ball4

canvas.update()

print(f"ball4 == ball5 ? {ball4 == ball5}")

print(f"ball1 == ball5 ? {ball1 == ball5}")

print(ball1)

print(ball2)

print(ball3)

print(ball4)

Output:

ball4 == ball5 ? False

ball1 == ball5 ? False

<__main__.Ball object at 0x10484f1d0>

<__main__.Ball object at 0x10484f208>

<__main__.Ball object at 0x10484f240>

<__main__.Ball object at 0x10484f278>

This is probably not what we want! ball4 and ball5 should be equal, and when we print out a ball, we don't get a very useful output.

Here is an example of the __str__ method of our Ball class:

def __str__(self):

"""

Creates a string that defines a Ball

:return: a string

"""

ret_str = ""

ret_str += (f"x=={self.x}, y=={self.y}, "

f"width=={self.width}, height=={self.height}, "

f"fill=={self.fill}")

return ret_str

We create a string with the attributes we care to print, and then we return the string.

Slide 11

def __eq__(self, other):

return (

self.canvas == other.canvas and

self.x == other.x and

self.y == other.y and

self.width == other.width and

self.height == other.height and

self.fill == other.fill

)

We perform the comparison on the two different balls, and return True if they are the same, and False otherwise.

Slide 12

There are other, related methods you can also create:

- ne (not equal). In Python 3, we don't usually bother creating this, because the language just treats != as the opposite of ==.

__lt__(less than)__le__(less than or equal to)__gt__(greater than)__ge__(greater than or equal to)

There isn't necessarily a good way to determine if a ball is "less than" another ball, but for some objects it makes more sense.

Slide 13