Slide 1

Today: dict output, wordcount.py example program, list functions, List patterns, state-machine pattern

Slide 2

Dict Load-Up vs. Output

- Thus far we have concentrated on loading data into the dict

- e.g. dict-count algorithm

- Typical program pattern: read data file, load up dict, then do something with dict

- A common pattern: dump out all the data organized in the dict

- e.g. wordcount below - read file, print out index of all words

Slide 3

dict.keys()

- The function

dict.keys()returns a list-like collection of the dict keys - The keys are in a "random" order

Actually it's the order they were added

But it's random-looking to the end user - There's also a .values() that is seldom used

>>> # Load up dict

>>> d = {}

>>> d['a'] = 'alpha'

>>> d['g'] = 'gamma'

>>> d['b'] = 'beta'

>>>

>>> # d.keys() - list-like "iterable" of keys, suitable for foreach etc.

>>> d.keys()

dict_keys(['a', 'g', 'b'])

>>>

>>> # d.values() - list of values, typically don't use this

>>> d.values()

dict_values(['alpha', 'gamma', 'beta'])

Slide 4

Dict Output Code

Loop over d.keys(), for each key, look up its value. This works fine,

the only problem is that the keys are in random order.

>>> for key in d.keys():

... print(f'{key} -> {d[key]}')

...

a -> alpha

g -> gamma

b -> beta

Slide 5

Dict Output sorted(d.keys())

- The function

sorted(x)takes in any linear collection - Returns a new list with those elements, sorted into increasing order (more later)

- Works with

d.keys() - So below is the standard way to print out a dict with the keys in sensible order

>>> sorted(d.keys())

['a', 'b', 'g']

>>>

>>> for key in sorted(d.keys()):

... print(f'{key} -> {d[key]}')

...

a -> alpha

b -> beta

g -> gamma

Slide 6

Using .items() to get keys and values simultaneously from a dict

There is a common pattern where you want to get each key/value pair out of a dict. One way to do it is to use a regular for in loop to get the keys, and then extract the values from the dict as a separate step:

>>> animals = {'fox': 20, 'bear': 5, 'chicken': 12}

>>> for animal in animals:

... animal_value = animals[animal]

... print(f"Chris's 2½ year old daughter said {animal} {animal_value} times today.")

...

Chris's 2½ year old daughter said fox 20 times today.

Chris's 2½ year old daughter said bear 5 times today.

Chris's 2½ year old daughter said chicken 12 times today.

>>>

The following is a way to get the key/value pairs simultaneously, using the .items() method of a dict:

>>> for animal, animal_value in animals.items():

... print(f"Chris's 2½ year old daughter said {animal} {animal_value} times today.")

...

Chris's 2½ year old daughter said fox 20 times today.

Chris's 2½ year old daughter said bear 5 times today.

Chris's 2½ year old daughter said chicken 12 times today.

>>>

This latter method is common, but often new programmers forget the .items():

>>> for animal, animal_value in animals:

... print(f"Chris's 2½ year old daughter said {animal} {animal_value} times today.")

...

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 2)

>>>

Slide 7

WordCount Example Code - Rosetta Stone!

The word count program is a sort of Rosetta stone of coding - it's a working demonstration of many important features of a computer program: strings, dicts, loops, parameters, return, decomposition, testing, sorting, files, and main(). The complete text of wordcount.py is at the end of this page for reference. Like you need to remember some bit of Python syntax, there's a good chance there's an example in this program. Of if you are learning a new computer language, you could try to figure out how to write wordcount in it to get started.

Slide 8

Wordcount Data Flow

- Given a filename

- Reads through all the words

- Cleans the puncutation off each word so '--"hi"-' becomes 'hi'

- Builds a dict-count of all the words in lowercase form

- Once loaded, prints them all out in alphabetic order, 1 word/count per line

Slide 9

Sample Run

Note how words are cleaned up

$ cat poem.txt

Roses are red

Violets are blue

"RED" BLUE.

$

$ python3 wordcount.py poem.txt

are 2

blue 2

red 2

roses 1

violets 1

Slide 10

Dict-Count Code

def read_counts(filename):

"""

Given filename, reads its text, splits it into words.

Returns a "counts" dict where each word

is the key and its value is the int count

number of times it appears in the text.

Converts each word to a "clean", lowercase

version of that word.

The Doctests use little files like "test1.txt" in

this same folder.

>>> read_counts('test1.txt')

{'a': 2, 'b': 2}

>>> read_counts('test2.txt') # Q: why is b first here?

{'b': 1, 'a': 2}

>>> read_counts('test3.txt')

{'bob': 1}

"""

with open(filename) as f:

text = f.read() # demo reading whole string vs line/in/f way

# once done reading - do not need to be indented within open()

counts = {}

words = text.split()

for word in words:

word = word.lower()

cleaned = clean(word) # style: call clean() once, store in var

if cleaned != '': # subtle - cleaning may leave only ''

if cleaned not in counts:

counts[cleaned] = 0

counts[cleaned] += 1

return counts

Slide 11

Dict Output Code

In the wordcount.py .. the totally standard dict output code is used to print out the words and their counts.

def print_counts(counts):

"""

Given counts dict, print out each word and count

one per line in alphabetical order, like this

aardvark 1

apple 13

...

"""

for word in sorted(counts.keys()):

print(word, counts[word])

Slide 12

Timing Tests

Try more realistic files. Try the file

alice-book.txt - the full text of Alice in Wonderland full text, 27,000 words. tale-of-two-cities.txt\

- full text, 133,000 words. Time the run of the program, see if the dic†/hash-table is as fast as they say with the command line "time" command. The second run will be a little faster, as the file is cached by the operating system.

$ time python3 wordcount.py alice-book.txt

...

...

youth 6

zealand 1

zigzag 1

real 0m0.103s

user 0m0.079s

sys 0m0.019s

Here "real 0.103s" means regular clock time, 0.103 of a second, aka 103 milliseconds elapsed to run this command.

Windows PowerShell equivalent to "time" the run of a command:

$ Measure-Command { py wordcount.py alice-book.txt }

There are 33000 words in alice-book.txt. Each word hits the dict 3 times: 1x "in", then at least 1 get and 1 set for the +=. So how long does each dict access take?

>>> 0.103 / (33000 * 3)

1.0404040404040403e-06

So with our back-of-envelope math here, the dict is taking something less than 1 millionth of a second per access. In reality it's faster than that, as we are not separating out the for the file reading and parsing which went in to the 0.103 seconds.

Try it with tale-of-two-cities.txt which is 133000 words. This will better spread out the overhead, so get a lower time per access.

Slide 13

List 1.0 Features

See also Python guide Lists

- You can get quite far with just these basics

lst = [1, 2, 3]lst.append(4)to addlen(lst)lst[2]access- Tests:

in/not in - loop 1:

for elem in lst: - loop 2:

for i in range(len(lst)): - slices (below)

>>> nums = []

>>> nums.append(1)

>>> nums.append(0)

>>> nums.append(6)

>>>

>>> nums

[1, 0, 6]

>>>

>>> 6 in nums

True

>>> 5 in nums

False

>>> 5 not in nums

True

>>>

>>> nums[0]

1

>>>

>>> for num in nums:

... print(num)

...

1

0

6

Slide 14

List Slices

- Slices work with lists

- Exactly like Strings

lst[start:end]

Elements starting at start

Up to but not including end- Creates a new list

- Populated with elements from original list

lst[:]copies the whole listlst[-1]is the last element

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> lst2 = lst[1:] # slice without first elem

>>> lst2

['b', 'c']

>>> lst

['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> lst3 = lst[:] # copy whole list

>>> lst3

['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> # can prove lst3 is a copy, modify lst

>>> lst[0] = 'xxx'

>>> lst

['xxx', 'b', 'c']

>>> lst3

['a', 'b', 'c']

Slide 15

lst.pop([optional index])

- Need something the opposite of .append()

- How to pull elements out of a list, shrinking it?

lst.pop()- removes last elem from list, returning it- Mnemonic: opposite of append()

pop(index)- takes an optional index number- Pops off that element instead of the end one

pop(0)- pops the first element- The list elements are kept in a contiguous block

Shifting elements over so they are indexed 0..len(lst)-1 - Error if the list is empty - reasonable!

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c']

['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> lst.pop() # opposite of append

'c'

>>> lst

['a', 'b']

>>> lst.pop(0) # can specify index

'a'

>>> lst

['b']

>>> lst.pop()

'b'

>>> lst.pop()

IndexError: pop from empty list

>>>

Slide 16

List 2.0 Features

Below are lesser features. If a CS106A problem would use one of these, the problem statement will mention it.

Here are some "list2" problems on these if you are curious, but you do not need to do these.

> list2 exercises

Slide 17

lst.extend(lst2)

- Unlikely to use in CS106A - mentioning for completeness

lst.extend(lst2)- Make lst longer with lst2 elements

a = [1, 2]

b = [3, 4]

a.extend(b)

Now a is[1, 2, 3, 4]- append() is super common

- extend() in the related, rare function

- See questions below:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [4, 5]

>>> a.append(b)

>>> # Q1 What is a now?

>>>

>>>

>>>

>>> a

[1, 2, 3, [4, 5]]

>>>

>>> c = [1, 3, 5]

>>> d = [2, 4]

>>> c.extend(d)

>>> # Q2 What is c now?

>>>

>>>

>>>

>>> c

[1, 3, 5, 2, 4]

Slide 18

Alternative: lst1 + lst2

lst1 + lst2- create bigger list of all their elements

Like string+leaves the original lists unchanged- Constructs a new list to hold answer

vs .extend() modifies existing list

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [9, 10]

>>> a + b

[1, 2, 3, 9, 10]

>>> a # original is still there

[1, 2, 3]

Slide 19

lst.insert(index, elem)

- Unlikely to use in CS106A - mentioning for completeness

lst.insert(index, elem)- insert at given index- Alternative to append()

- Elements in list are shifted over automatically

>>> lst = ['a', 'b']

>>> lst.insert(0, 'z')

>>> lst

['z', 'a', 'b']

Slide 20

lst.remove(target)

- Unlikely to use in CS106A - mentioning for completeness

lst.remove(xxx)- search for and remove first xxx elem- Error if it's not there already - use in to check

- Observe: append(), extend(), pop(), insert(), remove() .. all modify

the list

In contrast to immutable string, functions always return new strings

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'b']

>>> lst.remove('b')

>>> lst

['a', 'c', 'b']

Now we'll look some functions we will use.

Slide 21

1. sorted()

- sorted() takes in list, or list-like collection

e.g. range() or dict.keys()' - sorted uses the operator

<

5 < 6 -> True

'apple' < 'banana' -> True - Creates and returns increasing order sorted list

Original list is not changed - int elements - numeric ordering

- string elements - alphabetical, starting with leftmost char

Uppercase before lowercase, deal with this later - has reverse=True optional "named" parameter

Named params like this: no space around= - Error to mix int/str elements

- Remember: sorting is somewhat costly, don't do it for no reason

CS106B: implement your own sorting

>>> sorted([45, 100, 2, 12]) # numeric

[2, 12, 45, 100]

>>>

>>> sorted([45, 100, 2, 12], reverse=True)

[100, 45, 12, 2]

>>>

>>> sorted(['banana', 'apple', 'donut']) # alphabetic

['apple', 'banana', 'donut']

>>>

>>> sorted(['45', '100', '2', '12']) # wrong-looking, fix later

['100', '12', '2', '45']

>>>

>>> sorted(['45', '100', '2', '12', 13])

TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'int' and 'str'

Slide 22

2. min(), max()

- These are related to sorted() - returning 1 elem

- Use this builtin to pick out smallest/largest value

- Works with several params, or with a list

- Works with int

- Works with str

- Works with anything where "<" has meaning

- Error with empty list, must have at least 1 value

- Note not object noun.verb style, a function like sorted()

- min()/max() much faster than sorted() - use these if just need the one value

- Style reminder:

Don't use the name of a built-in function as a variable name

e.g. don't use "min" or "max" as a var name, though it's very tempting!

>>> min(1, 3, 2)

1

>>> max(1, 3, 2)

3

>>> min([1, 3, 2]) # lists work

1

>>> min([1]) # len-1 works

1

>>> min([]) # len-0 is an error

ValueError: min() arg is an empty sequence

>>> min(['banana', 'apple', 'zebra']) # strs work too

'apple'

>>> max(['banana', 'apple', 'zebra'])

'zebra'

Slide 23

sum()

Compute the sum of a collection of ints or floats, like +.

>>> nums = [1, 2, 1, 5]

>>> sum(nums)

9

Slide 24

"State Machine" Pattern

When you're looking at a problem, you never want to think of it as this brand new thing you've never solved before. There's always parts of it that are idiomatic, or following some pattern you've seen before. The familiarity makes them easy to write, easy to read. We put in the pattern code where we can, adding needed custom code around it.

Slide 25

List Code Pattern Examples

Look at the "listpat" exercises on the experimental server

> listpat exercises

Slide 26

State-Machine Pattern

- Have a "state" variable

- 1. Init the variable before the loop

- 2. Loop over the elements. For each element, look at or update the state

- 3. After the loop, use state variable to compute the final result

Slide 27

Previously: += Accumulate Result

Many functions we've done before actually fit the state-machine pattern, e.g. double_char(). We have a "result" set to empty before the loop. Something gets appended to result in the loop, possibly with some logic. We've used this with both strings (+=) and lists (.append).

# 1. init state before loop

result = ''

loop:

....

# 2. update state in the loop

if xxx:

result += yyy

# 3. Use state to compute result

return result

Slide 28

AKA "map"

With lists, this is sometimes called a "map" or "mapping", as the computation takes in a list length N of inputs, and computes an output list length N of outputs. We'll see this map idea again.

Slide 29

State-Machine "count" Strategy

- Simple example of a state variable

- A fairly common problem, so this pattern is good to know

- Say want to count occurrences of target value in list

- Init before loop:

count = 0 - Each iteration may do:

count += 1 counthold the final count after all iterations- Similar algorithms...

- e.g. sum up all ints in a list

# 1. init count to 0

count = 0

loop:

....

# 2. increment count in some cases

if xxx:

count += 1

# 3. Count is the answer after the loop

return count

Slide 30

Example: count_target()

count_target(): Given a list of ints and a target int, return the int count number of times the target appears in the list. Solve with a foreach + "count" variable.

Solution Code

def count_target(nums, target):

count = 0

for num in nums:

if num == target:

count += 1

return count

Extra: sumpat() - sum up list of ints, same pattern.

Slide 31

State-Machine Exercise: min()

> min()

- min() function - exercise / example - walk through in lecture

- Given list of numbers, return the min value

- Keep "best" state variable - smallest element seen

- Initially use lst[0] as the best

- Foreach over the numbers, update best for each number

Is this number I'm looking at the new best?

Style note: we have Python built-in functions like min() max() len() list(). Avoid creating a variable with the same name as an important function, like "min" or "list". This is whey our solution uses "best" as the variable to keep track of the smallest value seen so far instead of "min".

Slice note: one odd thing in this solution is that it uses element [0]

as the best initially, and then the loop will uselessly < compare best

to element [0] on its first iteration. Could iterate over nums[1:]

to avoid this useless comparison. But that would copy the entire list to

avoid a single comparison, a bad tradeoff. Therefore it's better to

just keep it as simple as possible, looping over the whole list in the

standard way. Also, we prefer code with the correct answer that is

readable, and our solution is good at both of those.

Solution (and note that we've chosen to use min as the function name – bad idea! Why?)

def min(nums):

# best tracks smallest value seen so far.

# Compare each element to it.

best = nums[0]

for num in nums:

if num < best:

best = num

return best

Slide 32

State-Machine - digit_decode()

Say we have a code where most of the chars in s are garbage. Except each time there is a digit in s, the next char goes in the output. Maybe you could use this to keep your parents out of your text messages in high school.

'xxyy9H%vvv%2i%t6!' -> 'Hi!'

Slide 33

How Might You Solve This?

I can imagine writing a while loop to find the first digit, then taking the next char, .. then the while loop again ... ugh.

Slide 34

Solution: State-Machine

Have a boolean variable take_next which is True if the next char

should be taken (i.e. the char of the next iteration of the loop). Write

a nice, plain loop through all the chars. Set take_next to True when

you see a digit. For each char, look at take_next to see if it should

be taken. The details of the code in the loop are subtle, hard to get

right the first time. However, the bugs I would say are not hard to

diagnose when you see the output. So just put some code in there and set

about debugging it.

Slide 35

digit_decode() Solution

def digit_decode(s):

result = ''

take_next = False

for ch in s:

if take_next:

result += ch

take_next = False

if ch.isdigit():

take_next = True

# Set take_next at the bottom of the

# loop, taking effect on the next char

# at the top of the loop.

return result

Slide 36

State-Machine - "previous" Technique

- A classic state-machine technique (CS106B uses this one)

- Challenge: how many elems are the same as the elem to their left

- Have a "previous" state var

- Before the loop, init previous with a harmless value, e.g.

Noneor'' - Last line in loop:

previous = elem - Then for each loop iteration:

Have current element

Have "previous", the value from the previous loop iteration

Previous pattern:

# 1. Init with not-in-list value

previous = None

for elem in lst:

# 2. Use elem and previous in loop

# 3. last line in loop:

previous = elem

Slide 37

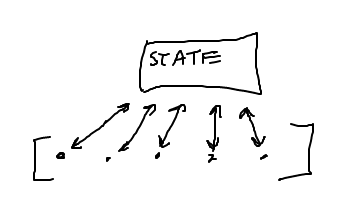

Previous Drawing

Here is a visualization of the "previous" strategy - the previous

variable points to None, or some other chosen init value for the first

iteration of the loop. For later loops, the previous variable lags one

behind, pointing to the value from the previous iteration.

Slide 38

Example - count_dups()

count_dups(): Given a list of numbers, count how many "duplicates" there are in the list - a number the same as the value immediately before it in the list. Use a "previous" variable.

Slide 39

count_dups() Solution

The init value just needs to be some harmless value such that the ==

test will be False. None often works for this.

def count_dups(nums):

count = 0

previous = None # init

for num in nums:

if num == previous:

count += 1

previous = num # set for next loop

return count

Slide 40

(optional) State-Machine Challenge - hat_decode()

A neat example of a state-machine approach.

The "hat" code is a more complex way way to hid some text inside some

other text. The string s is mostly made of garbage chars to ignore.

However, '^' marks the beginning of actual message chars, and '.'

marks their end. Grab the chars between the '^' and the '.',

ignoring the others:

'xx^Ya.xx^y!.bb' -> 'Yay!'

Solving using a state-variable "copying" which is True when chars should be copied to the output and False when they should be ignored. Strategy idea: (1) write code to set the copying variable in the loop. (2) write code that looks at the copying variable to either add chars to the result or ignore them.

There is a very subtle issue about where the '^' and '.' checks go

in the loop. Write the code the first way you can think of, setting

copying to True and False when seeing the appropriate chars. Run the

code. If it's not right (very common!), look at the got output. Why

are extra chars in there?

For reference - source code for wordcount

Slide 41

WordCount Example Code

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Stanford CS106A WordCount Example

Nick Parlante

Counting the words in a text file is a sort

of Rosetta Stone of programming - it uses files, dicts, functions,

loops, logic, decomposition, testing, command line in main().

Trace the flow of data starting with main().

There is a sorted/lambda exercise below.

Code is provided for alphabetical output like:

$ python3 wordcount.py somefile.txt

aardvark 12

anvil 3

boat 4

...

**Exercise**

Implement code in print_top() to print the n most common words,

using sorted/lambda/items.

Then command line -top n feature calls print_top() for output like:

$ python3 wordcount.py -top 10 alice-book.txt

the 1639

and 866

to 725

a 631

she 541

it 530

of 511

said 462

i 410

alice 386

"""

import sys

def clean(s):

"""

Given string s, returns a clean version of s where all non-alpha

chars are removed from beginning and end, so '@@x^^' yields 'x'.

The resulting string will be empty if there are no alpha chars.

>>> clean('$abc^') # basic

'abc'

>>> clean('abc$$')

'abc'

>>> clean('^x^') # short (debug)

'x'

>>> clean('abc') # edge cases

'abc'

>>> clean('$$$')

''

>>> clean('')

''

"""

# Good examples below of inline comments: explain

# the *goal* of the lines, not repeating the line mechanics.

# Lines of code written for teaching often have more inline

# comments like this than regular production code.

# Move begin rightwards, past non-alpha punctuation

begin = 0

while begin < len(s) and not s[begin].isalpha():

begin += 1

# Move end leftwards, past non-alpha

end = len(s) - 1

while end >= begin and not s[end].isalpha():

end -= 1

# begin/end cross each other -> nothing left

if end < begin:

return ''

return s[begin:end + 1]

def read_counts(filename):

"""

Given filename, reads its text, splits it into words.

Returns a "counts" dict where each word

is the key and its value is the int count

number of times it appears in the text.

Converts each word to a "clean", lowercase

version of that word.

The Doctests use little files like "test1.txt" in

this same folder.

>>> read_counts('test1.txt')

{'a': 2, 'b': 2}

>>> read_counts('test2.txt') # Q: why is b first here?

{'b': 1, 'a': 2}

>>> read_counts('test3.txt')

{'bob': 1}

"""

with open(filename) as f:

text = f.read() # demo reading whole string vs line/in/f way

# once done reading - do not need to be indented within open()

counts = {}

words = text.split()

for word in words:

word = word.lower()

cleaned = clean(word) # style: call clean() once, store in var

if cleaned != '': # subtle - cleaning may leave only ''

if cleaned not in counts:

counts[cleaned] = 0

counts[cleaned] += 1

return counts

def print_counts(counts):

"""

Given counts dict, print out each word and count

one per line in alphabetical order, like this

aardvark 1

apple 13

...

"""

for word in sorted(counts.keys()):

print(word, counts[word])

# Alternately can use counts.items() to access all key/value pairs

# in one step.

# for key, value in sorted(counts.items()):

# print(key, value)

def print_top(counts, n):

"""

(Exercise)

Given counts dict and int n, print the n most common words

in decreasing order of count

the 1639

and 866

to 725

...

"""

items = counts.items()

# To get a start writing the code, could print raw items to

# get an idea of what we have.

# print(items)

# Your code here - our solution is 3 lines long, but it's dense!

# Hint:

# Sort the items with a lambda so the most common words are first.

# Then print just the first n word,count pairs

pass

items = sorted(items, key=lambda pair: pair[1], reverse=True) # 1. Sort largest count first

for word, count in items[:n]: # 2. Slice to grab first n

print(word, count)

def main():

# (provided)

# Command line forms

# 1. filename

# 2. -top n filename # prints n most common words

args = sys.argv[1:]

if len(args) == 1:

# filename

counts = read_counts(args[0])

print_counts(counts)

if len(args) == 3 and args[0] == '-top':

# -top n filename

n = int(args[1])

counts = read_counts(args[2])

print_top(counts, n)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()