Slide 1

Today: Idiomatic phrases, "reverse" chronicles, Better/shorter code invariant, more string functions, unicode, list comprehensions

Today, I'll show you some techniques where we have code that is already correct, but we can write it in a better, shorter way. It's intuitively satisfying to have a 10 line thing, and shrink it down to 6 lines that reads better.

Slide 2

Technique: Build on Idiomatic Phrases

You can think of every program as having some phrases of stock, idiomatic code, and then some phrases that are custom, idiosyncratic bits particular to that algorithm. We'll just say, use the idiomatic bits where they come up — easy to type in, easy to understand. Build your needed changes around the idiomatic code. The first 3 reverse() solutions below work in this way.

Slide 3

The "Reverse" Rosetta Stone

> Reverse problems

How many ways can you think of to reverse a string in Python? A sort of parlor trick to see a series of python techniques worked out, compare them.

'Hello' -> 'olleH'

Aside: there is a scene in the Movie Amadeus where Motzart plays a piece one way, then gets under the piano, reaches hands up and plays it again upside down. I believe today this would be called a "flex"? In any case, it is reminiscent of the problem here of taking the normal thing and dong it backwards. youtube

Slide 4

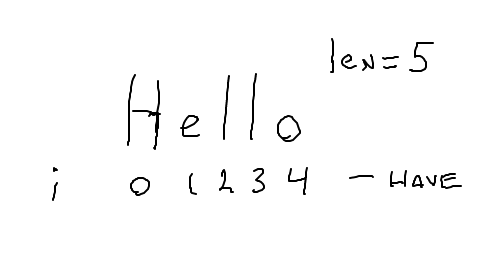

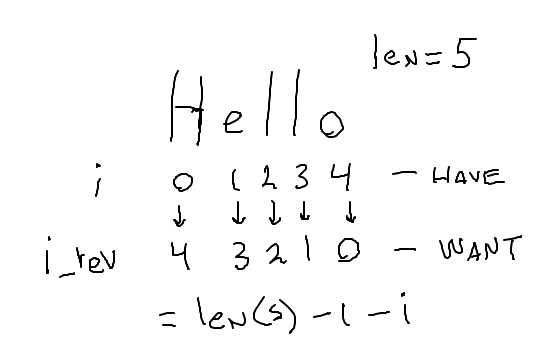

reverse1() - Muggle i_rev

We are very familiar with the idiomatic for i in range(len(s)),

running i through the index numbers from start to end: 0, 1, 2, ...

len-1. Start with that idiomatic loop. Think about computing an i_rev

from each i, which will go through the string backwards: the last

char, then the next to last, and so on. There turn out to be easier

ways, but this is a reasonable approach.

I think of this as the "muggle" solution - using intricate devices to get the effect where there are easier ways. We could give this full credit, possibly pointing out the easier ways to do it.

Sketch out the idea on this drawing

Something like this:

Slide 5

reverse2() - reversed()

Using the well known, idiomatic for i in range(len(s)) is a good idea.

The reversed() function is less well known, yielding a sequence in

reverse order, but here it solves the problem very neatly.

Slide 6

reverse3() - +=

There's a very neat way to solve this using just the plain old

for ch in s loop. Think about how you might re-write the += line.

This is perhaps the most elegant, if non-obvious, solution, as it is

short and uses simple Python features.

Slide 7

reverse4() - while

Instead of reversed() and range(), could write a while loop to manually generate the index numbers in the order we want. This is no longer a great solution - doing manually something that range() and reversed() provide for free.

Slide 8

reverse5 and reverse6

Slide 9

These are more silly uses of Python techniques, although they are code patterns we will cover later in CS106A, so we can check these out then.

And one more thing…

There is one more way to reverse a string which is Pyhtonic and simple:

return s[::-1]

This slice means "take a slice of the entire string, going backwards by -1."

Slide 10

Technique: Better/Shorter - Unify Cases

> Better problems

Slide 11

Shorter Code - Better Code

- Sometimes you solve a problem, wonder if it can be done with fewer lines

- Often, though not always, a shorter solution seems better

It's possible to make code so short it's unreadable.

Readability being a CS106A goal, we'll never prefer that form - Today we'll look at Unify-Cases technique to shorten the code using a variable

Slide 12

Unify Cases with a Variable

- Suppose we have

Lines (a) for case-1

Lines (b) for case-2 - Re-write the code so one set of lines works for both cases

- Move the difference between the 2 cases into a variable

So the one set of lines can work - Hard to describe in the abstract, let's look at an example

Slide 13

speeding() Example

speeding(speed, birthday): Compute speeding ticket fine as function of speed and birthday boolean. Rule: speed under 55, fine is 100, otherwise

- If it's your birthday, the allowed speed is 5 mph more. Challenge: change this code to be shorter, not have so many distinct paths.

The code below works correctly. You can see there is one set of lines each for the birthday/not-birthday cases. What exactly is the difference between these two sets of lines?

def speeding(speed, birthday):

if not birthday:

if speed < 50:

return 100

else:

return 200

else: # is birthday

if speed < 55:

return 100

else:

return 200

Slide 14

Unify Cases Solution

- The 2 sets of lines look really similar

- They differ by the value in the if-test

- Solution: introduce "limit" variable

- limit holds the value that distinguishes 100/200 fines

- Code at the top can set the limit before the unified lines

- Don't need 2 if-statements

- Use 1 if-statement that uses limit

- Summary

Used to have if-stmt1 and if-stmt2

Set a variable above that lets a unified if-statement handle both cases - Minor: Can write without else, "pick off" return style

Slide 15

speeding() Better Unified Solution

def speeding(speed, birthday):

# Set limit var

limit = 50

if birthday:

limit = 55

# Unified: limit holds value to use.

# One if-stmt handles all cases

if speed < limit:

return 100

return 200

def match(a, b):

result = ''

# Set length to whichever is shorter

length = len(a)

if len(b) < len(a):

length = len(b)

for i in range(length):

if a[i] == b[i]:

result += a[i]

return result

Slide 16

ncopies() Demo/Exercise

Change this code to be better / shorter. Look at lines that are similar

- make an invariant.

ncopies(word, n, suffix): Given name string, int n, suffix string,

return n copies of string + suffix. If suffix is the empty string, use

'!' as the suffix. Challenge: change this code to be shorter, not have

so many distinct paths.

Before:

def copies(word, n, suffix):

result = ''

if suffix == '':

for i in range(n):

result += word + '!'

else:

for i in range(n):

result += word + suffix

return result

Slide 17

ncopies() Unified Solution

Solution: use logic to set "suffix" to hold the suffix to use for all cases. Later code just uses suffix vs. separate if-stmt for each case.

def copies(word, n, suffix):

result = ''

# Set suffix if necessary to value to use

if suffix == '':

suffix = '!'

# Unified: one loop, using suffix

for i in range(n):

result += word + suffix

return result

Slide 18

String - More Functions

See guide for details: Strings

Thus far we have done String 1.0: len, index numbers, upper, lower, isalpha, isdigit, slices, .find().

There are more functions. You should at least have an idea that these exist, so you can look them up if needed. The important strategy is: don't write code manually to do something a built-in function in Python will do for you. The most important functions you should have memorized, and the more rare ones you can look up.

Slide 19

s.startswith() s.endswith()

These are very convenient True/False tests for the specific case of checking if a substring appears at the start or end of a string. Also a pretty nice example of function naming.

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Py')

True

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Px')

False

>>> 'resume.html'.endswith('.html')

True

Slide 20

String - replace()

str.replace(old, new)- Returns a new string with replacements done (immutable)

- Does not respect word boundaries, just dumb replacement

- Aside: Anti-Pattern

Trying to compute something about s

e.g. count the digits in s

Do not use replace() to modify s as a shortcut to computing about s

Not a good strategy

>>> s ='this is it'

>>> s.replace('is', 'xxx') # returns changed version

'thxxx xxx it'

>>>

>>> s.replace('is', '')

'th it'

>>>

>>> s # s not changed

'this is it'

Slide 21

Recall: s.foo() Does Not Change s

Recall how calling a string function does not change it. Need to use the return value...

# NO: Call without using result:

s.replace('is', 'xxx')

# s is the same as it was

# YES: this works

s = s.replace('is', 'xxx')

Slide 22

String - strip()

- Removes whitespace chars from either end

- Use with

for line in fto trim off \n

>>> s = ' this and that\n'

>>> s.strip()

'this and that'

Slide 23

String - split()

- Nice feature to parse a line of text

e.g. from a file line11,45,19.2,N str.split()-> array of stringsstr.split(',')- split on','substringstr.split()- with zero parameters

a special form of split()

splits on 1 or more whitespace chars

combines multiple whitespace chars

handy primitive "word" from line feature

>>> s = '11,45,19.2,N'

>>> s.split(',')

['11', '45', '19.2', 'N']

>>> 'apple:banana:donut'.split(':')

['apple', 'banana', 'donut']

>>>

>>> 'this is it\n'.split() # special whitespace form

['this', 'is', 'it']

Slide 24

String - join()

- Reverse of split()

- Given list of strings, puts them together to make a big string

- Mnemonic: str.split() and str.join()

The string is the noun in noun.verb form

>>> foods = ['apple', 'banana', 'donut']

>>> ':'.join(foods)

'apple:banana:donut'

Slide 25

String Unicode

In the early days of computers, the ASCII character encoding was very common, encoding the roman a-z alphabet. ASCII is simple, and requires just 1 byte to store 1 character, but it has no ability to represent characters of other languages.

Each character in a Python string is a unicode character, so characters for all languages are supported. Also, many emoji have been added to unicode as a sort of character.

Every unicode character is defined by a unicode "code point" which is basically a big int value that uniquely identifies that character. Unicode characters can be written using the "hex" version of their code point, e.g. "03A3" is the "Sigma" char Σ, and "2665" is the heart emoji char ♥.

Hexadecimal aside: hexadecimal is a way of writing an int in base-16 using the digits 0-9 plus the letters A-F, like this: 7F9A or 7f9a. Two hex digits together like 9A or FF represent the value stored in one byte, so hex is a traditional easy way to write out the value of a byte. When you look up an emoji on the web, typically you will see the code point written out in hex, like 1F644, the eye-roll emoji 🙄.

You can write a unicode char out in a Python string with a \u followed

by the 4 hex digits of its code point. Notice how each unicode char is

just one more character in the string:

>>> s = 'hi \u03A3'

>>> s

'hi Σ'

>>> len(s)

4

>>> s[0]

'h'

>>> s[3]

'Σ'

>>>

>>> s = '\u03A9' # upper case omega

>>> s

'Ω'

>>> s.lower() # compute lowercase

'ω'

>>> s.isalpha() # isalpha() knows about unicode

True

>>>

>>> 'I \u2665'

'I ♥'

For a code point with more than 4-hex-digits, use \U (uppercase U) followed by 8 digits with leading 0's as needed, like the fire emoji 1F525, and the inevitable 1F4A9.

>>> 'the place is on \U0001F525'

'the place is on 🔥'

>>> s = 'oh \U0001F4A9'

>>> len(s)

4

Slide 26

List Comprehensions

Python is a language that has many features that aren't found in most other languages. We have already seen slices, which are pretty rare for other languages. Another very cool feature in Python is the idea of a list comprehension.

A list comprehension is a way to create a new list from a list you already have, and it has a powerful and snazzy syntax.

List comprehensions provide a shortcut for a traditional for loop where you are building up a new list from a current list. Take this for loop example:

>>> nums = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70]

>>> new_list = []

>>> for num in nums:

... new_list.append(num + 5)

...

>>> print(new_list)

[15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65, 75]

Not hard code to write, but a bit verbose. A list comprehension is a one-liner for the same process:

>>> nums = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70]

>>> new_list = [x + 5 for x in nums]

>>> print(new_list)

[15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65, 75]

>>>

Here is another example:

>>> nums = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70]

>>> divisible_by_four = [x for x in nums if x % 4 == 0]

>>> print(divisible_by_four)

[20, 40, 60]

>>>

What's going on here? In the first example, the new list was made up of all values in nums plus 5. In the second example, the new list filtered the original list and only picked out the values that were divisible by 4.

This is the full syntax for list comprehensions:

newlist = [expression for item in iterable if condition == True]

The first example above did not use a condition, but the expression was modified from the original values in the list (x + 5). The second example left the expression just as the item (x) but it used the condition.

Here is the simplest example (and too trivial for normal use):

>>> animals = ['bear', 'aardvark', 'bison', 'chicken', 'dog', 'cow', 'pig', 'horse']

>>> new_list = [x for x in animals]

>>> print(new_list)

['bear', 'aardvark', 'bison', 'chicken', 'dog', 'cow', 'pig', 'horse']

>>>

What if we wanted to get a list of just the animals with and i in their name? Easy:

>>> new_list = [x for x in animals if 'i' in x]

>>> print(new_list)

['bison', 'chicken', 'pig']

What if we wanted a list with 's' appended to the end of each animal's name?

>>> [x + 's' for x in animals]

['bears', 'aardvarks', 'bisons', 'chickens', 'dogs', 'cows', 'pigs', 'horses']

>>>

What if we wanted only the animals that start with the letter 'b' and we also wanted them to end with s?

>>> [x + 's' for x in animals if x.startswith('b')]

['bears', 'bisons']

>>>

Let's say we have a list of numbers, and we only wanted to pick out the positive ones?

>>> nums = [-5, 8, 2, -3, -9, 18, 4, 7, 10]

>>> [n for n in nums if n > 0]

[8, 2, 18, 4, 7, 10]

>>>

What if we had the same nums list and wanted to convert all the numbers to their positive representation times 100? We could use the abs function:

>>> nums = [-5, 8, 2, -3, -9, 18, 4, 7, 10]

>>> [abs(x) * 100 for x in nums]

[500, 800, 200, 300, 900, 1800, 400, 700, 1000]

As you can see, list comprehensions are powerful and can save lots of time.