Slide 1

Today: parsing, while loop vs. for loop, parse words out of string patterns, boolean precedence, variables

Slide 2

Data and Parsing

Here's some fun looking data...

$GPGGA,005328.000,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,2,07,1.3,22.5,M,-25.7,M,2.0,0000*70

$GPGSA,M,3,09,23,07,16,30,03,27,,,,,,2.3,1.3,1.9*38

$GPRMC,005328.000,A,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,0.00,256.18,221217,,,D*78

$GPGGA,005329.000,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,2,07,1.3,22.5,M,-25.7,M,2.0,0000*71

$GPGSA,M,3,09,23,07,16,30,03,27,,,,,,2.3,1.3,1.9*38

$GPRMC,005329.000,A,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,0.00,256.18,221217,,,D*79

$GPGGA,005330.000,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,2,07,1.3,22.5,M,-25.7,M,3.0,0000*78

$GPGSA,M,3,09,23,07,16,30,03,27,,,,,,2.3,1.3,1.9*38

...

- The above is what a GPS chip outputs

-buried deep in your phone, this is going on - A standard: NMEA

- NMEA_018 (wikipedia)

- Things to notice: it's just text

-a series of text lines ending with \n

-each line is made of chars - Text is a super common exchange format between systems

- "Parsing"

-Have "raw" text like this

-Find and pull out the data you want - If you want to play around with data sets, Kaggle has about a billion different data sets.

- You can download any of the data sets for free, but almost all will require some form of parsing and clean-up to get into a form you can easily use in your own Python programs.

- Some of the data sets are huge! Some would take way too long to process using Python without some significant thinking about how to look at the data efficiently (e.g., putting it into a queryable database, first).

Slide 3

Foreshadow: Advance With var += 1

- Framing for today's example

- Imagine a string on paper

- Finger is pointing at a char

- Move finger to the right, looking for something

- Python: have a var

iwith an index into string - e.g.

iis 4, pointing at the'a' i += 1.. like moving one to the right- e.g. looking for the space after 'abc'

'xx @abc x'

012345678

Slide 4

Compare for i/range vs. while

The for/i/range form is great for going through numbers which you know ahead of time - a common pattern in real programs. However, while is more flexible - can test on each iteration, stop at the right spot. Ultimately you need both forms.

Slide 5

while Equivalent of for/range

Use for/i/range if have a series of numbers to step through. That is a

common case, and for/i/range is perfect for it. We'll use while for

situations that require more flexibility.

for i in range(n)- go-to solution for that sequence- Can write this as a

while.. do steps manually - Three parts: init, test, update

- Use

range()for common cases - Use while where need fine control of i (examples to follow)

- Beware: easy to forget update step, result is infinite loop

for/range is so common .. we don't have muscle-memory for the update

Here is the while-equivalent to for i in range(n)

i = 0 # 1. init

while i < n: # 2. test

# use i

i += 1 # 3. update, loop-bottom (easy to forget)

Slide 6

Example while_double()

> while_double() (in parse1 section)

double_char() written as a while (using a range() is the better approach for this problem, so here just demonstrating for-while equivalence).

def while_double(s):

result = ''

i = 0

while i < len(s):

result += s[i] + s[i]

i += 1

return result

Test is i < len(s) - this is basically "is i valid". We'l use

this definition of valid index later.

Slide 7

Example: at_word()

> at_word() (in parse1 section)

'xx @abc xyz' -> 'abc'

at_word(s): We'll say an at-word is an '@' followed by zero or more

alphabetic chars. Find and return the alphabetic part of the first

at-word in s, or the empty string if there is none. So 'xx @abc xyz'

returns 'abc'.

- Realistic parsing problem, extracting the wanted part of a string

- Demonstrate several patterns on this one

- We'll re-use these patterns

- We'll work through this one carefully

- Points about this code:

Use str.find() to locate each @

Use a while to skip over alpha chars to find end

Use < len(s) to protect use of s[xxx]

Var names: search, at, end - try to keep things straight

Slide 8

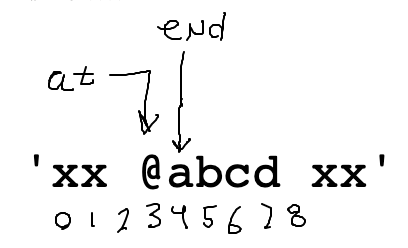

at_word() Strategy

First use s.find() to locate the '@'. Then start end pointing to

the right of the '@'. Use a while loop to advance end over the

alphabetic chars. Make a drawing below to sketch out this strategy.

Think about the while-test.

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

end = at + 1

# Advance end over alpha chars

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

'xx @abcd xx'

Slide 9

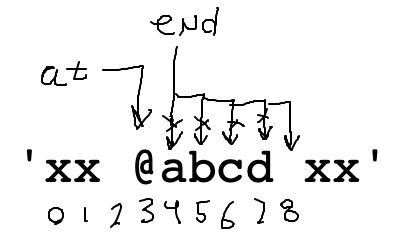

at_word() Loop: Advance End Over Alpha Chars

- AKA skip over the alpha chars

- Loop test: this is true = advance end one more

- Test:

s[end].isalpha() - Reminisce : Bit "true = go" pattern for moving forward

- This code will 90% work, with one case to fix later

- Loop leaves end pointing to the first non-alpha char

end = at + 1

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

Start of loop:

End of loop:

Slide 10

at_word(): Slice with end

Once we have at/end computed, pulling out the result word is just a slice.

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

Slide 11

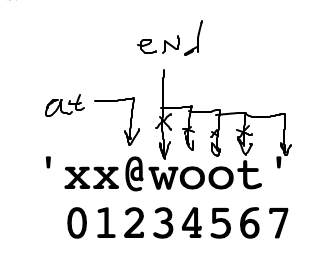

at_word: 'woot' Bug

That code is pretty good, but there is actually a bug in the while-loop. It has to do with particular form of input case below, where the alphabetic chars go right up to the end of the string. Think about how the loop works when advancing "end" for the case below.

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

'xx@woot'

01234567

Problem: keep advancing "end" .. past the end of the string,

eventually end is 7. Then the while-test s[end].isalpha() throws an

error since index 7 is past the end of the string.

The loop above translates to: "advance end so long as s[end] is alphabetic"

To fix the bug, we modify the test to: "advance end so long as s[end] is valid and alphabetic".

In other words, stop advancing if end reaches the end of the string.

Loop end bug:

Slide 12

Solution: end < len(s) Guard Test

We cannot access s[end] when end is too big. Add a guard test

end < len(s) before the s[end]. This stops the loop when end gets to

- The slice then works as before. This code is correct.

def at_word(s):

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

# Advance end over alpha chars

end = at + 1

while end < len(s) and s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

Slide 13

Guard / Short Circuit Pattern

The "and" evaluates left to right. As soon as it sees a False it

stops. In this way the < len(s) guard checks that "end" is a valid

number, before s[end] tries to use it. This a standard pattern: the

index-is-valid guard is first, then "and", then s[end] that uses the

index. We'll see more examples of this guard pattern.

Slide 14

Fix End Bug Recap

- Bug: run end off the end of s, testing non-existent

s[end] - e.g. this happens if input is

s = 'xx @woot'

Think through how the loop works for that case - Solution:

- Add guard

< - This is the fixed loop:

while end < len(s) and s[end].isalpha(): - Q: How to test if index

iis valid ins? - A:

i < len(s) - Only check

s[end]after checking thatendis valid - Boolean Short Circuit

Python evaluates expression left-right

As soon as boolean value determined, stops trying

AFalsein the midst of anandstops

So the<guards thes[end].isalpha() - Common guard pattern:

Checki < len(s)before tryings[i]

Slide 15

at_words() - Zero Char Case - Works?

- What about

'xx @ xx' - Consider slice of @ above

s[at + 1:end]

Turns out to be likes[4:4]

Which is the empty string'', so it works

Slide 16

Example exclamation()

exclamation(s): We'll say an exclamation is zero or more alphabetic chars ending with a '!'. Find and return the first exclamation in s, or the empty string if there is none. So 'xx hi! xx' returns 'hi!'. (Like at_word, but right-to-left).

Will need a guard here, as the loop goes right-to-left. The leftmost valid index is 0, so that will figure in the guard test.

Slide 17

Boolean Operators

- Arithmetic operators: + - * /

- Combine numbers to make a number

1 + 2 * 3 -> 7 - Boolean operators:

and or not - Combine Boolean values to make a Boolean

True or False -> True

True and False -> False

True and Not False -> True

Slide 18

Boolean Expressions

See the guide for details Boolean Expression

- Boolean operators:

and or not - Mixture of these, can add parenthesis to force order of operation

- Say have these variables:

age- int age, say age is good if less than 30

is_raining- boolean, True if raining

is_weekend- boolean, True if it's the weekend - Define: to be a good day, need two things:

- it must not be raining. This is mandatory.

- then either age is under 30 or it's the weekend

The code below looks reasonable, but doesn't quite work right

def good_day(age, is_weekend, is_raining):

if not is_raining and age < 30 or is_weekend:

print('good day')

Slide 19

Boolean Precedence:

not= highest, (like - in -7)and= next highest (like *)or= lowest (like +)

Slide 20

What The Above Does

Because and is higher precedence than or as written above, the code above acts like the following (the and going before the or):

if (not is_raining and age < 30) or is_weekend:

What is a set of data that this code will evaluate incorrectly?

raining=True, age=anything, weekend=True .. the or weekend makes the

whole thing True, no matter what the other values are. This does not

match the good-day definition above, which requires that it not be

raining.

Slide 21

Boolean Precedence Solution

The solution we will spell out is not difficult.

- Many programmers do not have boolean precedence memorized .. fine

- Do remember that "not" is the highest precedence

- Solution: note when you have a mixture of and + or

When there is a mixture, the precedence will matter

put in parenthesis in that case - We will never complain about parenthesis, so just add them to force the order you want

- In this case, put parens to group the or part, separating from not-raining

- BTW similar logic applies to math - if there's a mixture of * and +, add parenthesis

Solution

def good_day(age, is_weekend, is_raining):

if not is_raining and (age < 30 or is_weekend):

print('good day')

Slide 22

Parse "or" Example - at_word99()

This is operating at a realistic level for parsing data.

at_word99(): Like at-word, but with digits added. We'll say an at-word is an '@' followed by zero or more alphabetic or digit chars. Find and return the alpha-digit part of the first at-word in s, or the empty string if there is none. So 'xx \@ab12 xyz' returns 'ab12'.

Slide 23

"end" Loop For at_words99()

Like before, but now a word is made of alpha or digit - many real problems will need this sort of code. This may be our most complicated line of code thus far in the quarter! Fortunately, it's a re-usable pattern for any of these "find end of xxxx" problems.

The most difficult part is the "end" loop to locate where the word ends. What is the while test here? (Bring up at_word99() in other window to work it out). We want to use "or" to allow alpha or digit.

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while ??????????:

end += 1

'@a12'

01234

Slide 24

Solution

# 1. Still have the < guard

# 2. Use "or" to allow isalpha() or isdigit()

# 3. Need to add parens, since this has and+or combination

while end < len(s) and (s[end].isalpha() or s[end].isdigit()):

end += 1

Slide 25

at_word99() Solution

def at_word99(s):

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

# Advance end over alpha or digit chars

# use "or" + parens

end = at + 1

while end < len(s) and (s[end].isalpha() or s[end].isdigit()):

end += 1

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

Slide 26

We Need To Have a Little Talk About Variable Names

With the following code, it's clear that the assignment = sets the

variable to point to a value.

x = 7

Slide 27

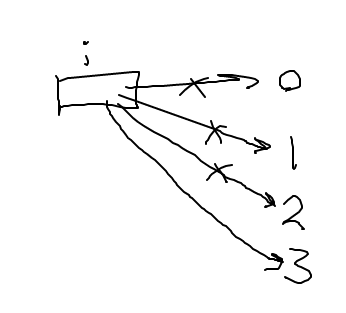

For Loop Sets Variables Too

It's less obvious, but the for loop just sets a variable too, once for

each iteration. The variable name is the word the programmer chooses

right after the word "for", in this example the variable is i which

is an idiomatic choice:

for i in range(4):

# use i

print(i)

0

1

2

3

Slide 28

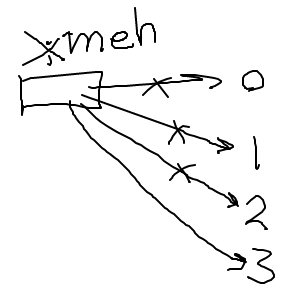

Variables and Meaninglessness

The Sartre of Coding!

The variable name is just the label applied to the box that hold the pointer.

You might get the feeling in CS106A to this point: it will only work if the variable is named "i", but that's not true. We named it "i" since that's the idiom, but it's not a requirement.

We try to choose a sensible label to keep our own thoughts organized.

However the computer does not care about the word used, so long as the

word chosen is used consistently across lines. The variable name i is

idiomatic for that sort of loop. But in reality we could use any

variable name, and the code would work exactly the same. Say we name the

variable meh instead .. same output. All that matters is that the

variable on line 1 is the same as on line 2.

for meh in range(4):

print(meh)

Output:

0

1

2

3

This is a little disturbing. We do try to choose good and/or idiomatic variable names for our own sake. However, the computer does not notice or care about the actual word choice for our variables.

Slide 29

If there is time: the set data structure (and a bonus: the split() function)

Lists work great for many different problems, but sometimes we want to store data in a slightly different way. For example, let's say we wanted to look through all of the words in a piece of text, and keep track of only the words, with no duplicates. How could we do this in Python? We could do it with a list:

def list_all_words(filename):

all_words = []

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

words = line.split() # create a list of the words on a line

for word in words:

if word not in all_words:

all_words.append(word)

return all_words

This works fine, but it is actually quite slow – every time we need to see if a word is in the list already, Python has to look at every word currently in the list and do a comparison.

A better way is to us a data structure that doesn't even allow duplicates, and has much faster determination if an element is in the data structure. In Python, we can use a set to do this. A set is a data structure that ignores all duplicated values when you add them to the set, and it is much faster:

def list_all_words(filename):

all_words = set() # creates an empty set

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

words = line.split() # create a list of the words on a line

for word in words:

all_words.add(word) # note 'add' instead of 'append'

return all_words