Slide 1

Today: string in/not-in, foreach, start lists, how to write main()

Slide 2

Patterns

When writing a new function, it's natural to draw upon similar functions you have written before. In CS, this is called the "patterns" strategy. You can quickly type in the common part of the pattern, and that code is familiar and easy and reliable. Then concentrate on what is different about the problem at hand.

Slide 3

Accumulate Pattern

For strings we have used an "accumulate" pattern many times. Start art off with the empty string, add something to the end of the result string in the loop.

result = ''

loop

result += something

return result

Slide 4

Quick Return Pattern

- Loop over collection, looking for X

If an element matches X, return answer immediately - Last line of function

Something like:return None

This is the "not found" case

Only runs if there was no Xs

Slide 5

Example: first_alpha()

> first_alpha() (in string3 section)

Given a string s, return the first alphabetic char in s, or None if

there is no alphabetic char. Demonstrates quick-return pattern.

We are not building a whole new string. In this case, we're finding one char in the string and returning it.

'123abc' -> 'a'

'123-456' -> None

1. Hinges on the fact that return exits the function immediately, so we can nest the return inside a loop or if-statement, structured to return a result immediately if the code finds one.

2. If the code gets to the end of the loop, the condition was never found. Like the Sherlock Holmes - "The Dog that did not bark", the loop never hits a true test. So what can we conclude about the string? In this case, there are no alpha chars in the string.

Slide 6

first_alpha() Solution

def first_alpha(s):

for i in range(len(s)):

# 1. Return immediately if found

if s[i].isalpha():

return s[i]

# 2. If we get here,

# there was no alpha char.

return None

Slide 7

Optional Exercise: has_digit()

'abc123' -> True

'abc' -> False

Use quick-return strategy, returning True or False.

Given a string s, return True if there is a digit in the string somewhere, False otherwise.

Solution - same pattern as first_alpha(), but returns boolean instead of a char

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

# 1. Exit immediately if found

return True

# 2. If we get here,

# there was no digit.

return False

Slide 8

More String Features - String4

On server see String4 - examples of features below: "foreach" and "in"

Slide 9

Recall: String in Test

- String

in- test if a substring appears in a string - Chars must match exactly - upper/lower are considered different

aka "case sensitive" - This is True/False test - use .find() to know where substring is

- Mnemonic: Python re-uses the word "in" from the for loop

- Style: don't write code for something that Python has built-in

>>> 'c' in 'abcd'

True

>>> 'bc' in 'abcd' # works for multiple chars

True

>>> 'bx' in 'abcd'

False

>>> 'A' in 'abcd' # upper/lower are different

False

Slide 10

Variant: not in

The form not in inverts the in test, True if the substring is not in the big thing. This is readability feature, as "not in" reads very naturally in the code. The "not in" form is preferred for expressing this sort of not-in-there test.

>>> 'x' not in 'abcd'

True

>>> 'bc' not in 'abcd'

False

Say for example we have a string of bad_chars, and we want to print a

char if it is not bad. Using the "not in" form, the code reads nicely.

if ch not in bad_chars:

print(ch)

We could use regular "in", and then add a "not" to its left, like the following form. This works, but the "not in" form is the preferred style and reads better.

if not ch in bad_chars:

print(ch)

Slide 11

We've Had a Good Run: for i in range(len(s)):

Good old for/i/range .. we've gotten a lot of use out of that to loop over the index numbers for a collection. But there's a new sherif in town!

Slide 12

Loop over chars: for ch in s:

- There is a second, easier way to loop over the chars in a string

for ch in s:- aka the "foreach" loop

- Loops over all the chars in

s, left to right - You do not get the index number here, just the char

- No square brackets [ ] in this form

- The variable name

chorcharis common for one character - Use this form if you do not need access to index numbers

- Use the for/i/range form if you need access to index numbers

for ch in s:

# use ch in here,

# will be one char from s

Slide 13

Example: double_char2()

Like earlier double_char, but using foreach.

Solution

def double_char2(s):

result = ''

for ch in s:

result = result + ch + ch

return result

Slide 14

Example: difference(a, b)

Demonstrates both foreach and in

difference(a, b): Given two strings, a and b. Return a version of a, including only those chars which are not in b. Use case-sensitive comparisons. Use a for/ch/s loop.

Solution

def difference(a, b):

result = ''

# Look at all chars in a.

# Check each against b.

for ch in a:

if ch not in b:

result += ch

return result

Slide 15

Optional Exercise: intersect2(a, b)

Slide 16

Python Lists

See the guide: Python List for more details about lists

- A list a linear collection of any type of python value

The formal name of the type is "list" - A very common type, up there with int and string

- Use list to store many of something

e.g. a thousand urls - a list of url strings

e.g. a million temperature readings - a list of float values - Things in a list are called "elements"

- "lst" is a generic list variable name

Slide 17

Lists are like Strings

- The design of Python tries to be consistent

- If something works for strings

- It likely works the same way for lists

- So you already know most of the list features!

- Same as string:

len(my_list)returns the number of elements

use[i]to access elements

elements indexed: 0 .. len-1

foreach loop

inworks - Differences:

Lists can contain any type of element

Lists are mutable Lists do not have a.find()function (we use.index())

Slide 18

Examples on Server list1

See the "list1" examples on the experimental server

- list_n() - create list [0, 1, 2, 3, ..n-1] - use range() and append()

- donut_index() - use "in" and index()

- list_censor() - use everything

Slide 19

1. List Literal: [1, 2, 3]

Use square brackets [..] to write a list in code (a "literal" list value), separating elements with commas. Python will print out a list value using this same square bracket format.

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> lst

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>>

"empty list" is just 2 square brackets with nothing within: []

Slide 20

2. Length of list: len(lst)

Use len() function, just like string. As a nice point of consistency, many things that work on strings work the same on lists - they are after all both linear collections using zero-based indexing.

>>> len(lst)

4

Slide 21

3. Square Brackets to access/change element

Use square brackets to access an element in a list. Valid index numbers are 0..len-1. Unlike string, can assign = to change an element within the list.

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> lst[0]

'a'

>>> lst[2]

'c'

>>>

>>> lst[0] = 'aaaa' # Change an elem

>>> lst

['aaaa', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>>

>>>

>>> lst[9]

Error:list index out of range

>>>

Slide 22

List Mutable

The big difference from strings is that lists are mutable - lists can be changed. Elements can be added, removed, changed over time. We'll look at four list features.

Slide 23

1. List append()

- Lists can contain any type (today int, str)

lst.append('something')- adds an element to the end of the list- The most important list function

- Modifies the list, returns nothing

- Common list-build pattern:

# 1. make empty list, then call .append() on it

>>> lst = []

>>> lst.append(1)

>>> lst.append(2)

>>> lst.append(3)

>>>

>>> lst

[1, 2, 3]

>>> len(lst)

3

>>> lst[0]

1

>>> lst[2]

3

>>>

>>> # 2. Similar, using loop/range to call .append()

>>> nums = []

>>> for i in range(6):

... nums.append(i * 10)

...

>>> nums

[0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

>>> len(nums)

6

>>> nums[5]

50

Slide 24

Common lst.append() Bug

The list.append() function modifies the existing list. It returns

None. Therefore the following code pattern will not work, setting lst

to None:

# NO does not work

lst = []

lst = lst.append(1)

lst = lst.append(2)

# Correct form

lst = []

lst.append(1)

lst.append(2)

# lst points to changed list

Slide 25

String vs. List .append()

Why do programmers write the incorrect form? Because the immutable string does use that pattern, and so you are kind of used to it:

# This works for string

# x = change(x) pattern

s = 'Hello'

s = s.upper()

s = s + '!'

# s is now 'HELLO!'

Slide 26

Example: list_n()

> list_n()

list_n(n): Given non-negative int n, return a list of the form [0, 1,

2, ... n-1]. e.g. n=4 returns [0, 1, 2, 3] For n=0 return the empty

list. Use for/i/range and append().

Solution

def list_n(n):

nums = []

for i in range(n):

nums.append(i)

return nums

Slide 27

2. List "in" / "not in" Tests

- How to tell if a value is in a list?

hint: like string! - The in operator tests if a value is in a list

- not in works too, reads nicely, preferred style

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> 'c' in lst

True

>>> 'x' in lst

False

>>> 'x' not in lst # preferred form to check not-in

True

>>> not 'x' in lst # equivalent form

True

Slide 28

3. Foreach On List

- for "foreach" loop works on a list

for var in list:- Probably the most common loop form

Many algorithms want to look at every element - The variable points to each element in turn, one element per loop

- No Change do not change the list - add/remove/change - during

iteration

Kind of reasonable rule: how would iteration work if elements left and appeared in the midst of iteration - Read the bullet above again – you should not change a list while you are iterating through it.

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> for s in lst:

... # use s in here

... print(s)

...

a

b

c

d

Slide 29

Example: intersect(a, b)

intersect(a, b): Given two lists a and b. Construct and return a new list made of all the elements in a which are also in b.

This code is very similar to the string code.

Slide 30

4. list.index(target) - Find Index of Target

- Similar to str.find(), but with one big difference

list.index(target)- returns int index of target if found- Flaw: list.index() only works if the target is in the list, failing with an error otherwise

- Code should check with

infirst, only call lst.index() if in is True - This design is annoying

It would be easier if lst.index() just returned -1, but it doesn't - Variant:

list.index(target, start_index)- begin search at start_index instead of 0

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> lst.index('c')

2

>>> lst.index('x')

ValueError: 'x' is not in list

>>> 'x' in lst

False

>>> 'c' in lst

True

Slide 31

Example: donut_index(foods)

donut_index(foods): Given "foods" list of food name strings. If 'donut' appears in the list return its int index. Otherwise return -1. No loops, use .index(). The solution is quite short.

Solution

def donut_index(foods):

if 'donut' in foods:

return foods.index('donut')

return -1

Slide 32

Optional: list_censor()

list_censor(n, censor): Given non-negative int n, and a list of "censored" int values, return a list of the form [1, 2, 3, .. n], except omit any numbers which are in the censor list. e.g. n=5 and censor=[1, 3] return [2, 4, 5]. For n=0 return the empty list.

Solution

def list_censor(n, censor):

nums = []

for i in range(n):

# Introduce "num" var since we use it twice

# Use "in" to check censor

num = i + 1

if num not in censor:

nums.append(num)

return nums

Slide 33

Style Note: Lists and the letter "s"

As your algorithms grow more complicated, with three or four variables running through your code, it can become difficult to keep straight in your mind which variable, say, is the number and which variable is the list of numbers. Many little bugs have the form of wrong-variable mixups like that.

Therefore, an excellent practice is to name your list variables ending with the letter "s", like "nums" above, or "urls" or "weights". Then when you have an append, or a loop, you can see the singular and plural variables next to each other, reassuring that you have it right.

url = (some crazy computation)

urls.append(url)

Or like this

for url in urls:

Slide 34

Constants in Python

STATES = ['CA, 'NY', 'NV', 'KY', 'OK']

- Simple form name=value at far left, not within a def

- This is a type of "global" variable

- A variable not inside a function

- In this case it is a constant for the program

- Functions can just refer to

STATESto get its value - Python Convention: upper case means its a constant

- Style: it's a read-only value, code should not modify it

Slide 35

ALPHABET Constant in HW4

# provided ALPHABET constant - list of the regular alphabet

# in lowercase. Refer to this simply as ALPHABET in your code.

# This list should not be modified.

ALPHABET = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z']

...

def foo():

for ch in ALPHABET: # this works

print(ch)

Slide 36

main() Function

You have called your code from the command line. The special function main() is the first function to run in a python program, and its job is looking at the command line arguments and figuring out what to do. With HW4, it's time for you to write your own main(). It's easier than you might think.

Slide 37

How Do Command Line Arguments Work? How to write main() code?

For details see guide: Python main() (uses affirm example too)

affirm.zip Example/exercise of main() command line args. You can do it yourself here, or just watch the examples below to see the ideas.

Slide 38

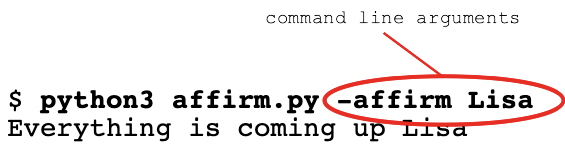

First Run To See The Arg

First run the code, see what the command line arguments (aka "args")

do:

-affirm and -hello options (aka "flags")

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

Everything is coming up Lisa

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

Looking good Bart

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Maggie

Today is the day for Maggie

$ python3 affirm.py -hello Bob

Hello Bob

$

Slide 39

Command Line Option e.g. -affirm

- Often a command lines select certain options or modes of the program

- e.g.

-affirmtells the program to print an affirmation - The convention is that each option starts with a dash, e.g.

-affirm - These are also known as "flags"

Slide 40

The "args" To a Program

The command line arguments, or "args", are the extra words you type on

the command line to tell the program what to do. The system is

deceptively simple - the command line arguments are just the words after

the program.py on the command line, separated from each other by

spaces. So in this command line:

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

The words -affirm and Lisa are the 2 command line args.

Slide 41

args Python List

When a Python program starts running, typically the run begins in a

special function named main(). This function can look at the command

line arguments, and figure out what other functions to call.

In our main() code the variable args is set up as a Python list

containing the command line args.

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

....

e.g. args = ['-affirm', 'Lisa']

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

....

e.g. args = ['-affirm', 'Bart']

Slide 42

Background: have print_affirm() etc. Functions to Call

For this example, say we have functions print_affirm(name) and

print_hello(name) which are already written. The main() function

will look at the args and call the appropriate functions. The key

pattern is that main() can call functions, passing in the right data as

their parameters.

Functions to call:

def print_affirm(name):

"""

Given name, print a random affirmation for that name.

"""

affirmation = random.choice(AFFIRMATIONS)

print(affirmation, name)

def print_hello(name):

"""

Given name, print 'Hello' with that name.

"""

print('Hello', name)

def print_n_copies(n, name):

"""

Given int n and name, print n copies of that name.

"""

for i in range(n):

# Print each copy of the name with space instead of \n after it.

print(name, end=' ')

# Print a single \n after the whole thing.

print()

Slide 43

How To Write main()

argsis a Python list of the args typed on the command line- Each typed arg is a string in the list

- If-statements in main() look at

args - One if-statement for each option/flag

- Demo: in main() try

print(args)to see the args list in action - (affirm.py code is done, use affirm-exercise.py to write the code)

- Look at

len(args) - Look at

args[0] - Call functions based on args

Pass in right data for each parameter

Slide 44

Exercise 1: Make -affirm Work

Make this command line work, editing the file affirm-exercise.py:

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -affirm Lisa

- Put in

print(args)first to see what the args list looks like len(args)- the number of argsargs[0]- the first arg- Strategy: check if there are 2 args and if first arg is '-affirm'

- The name to print is in

args[1]

Solution code

def main():

args = sys.argv[1:]

....

....

# 1. Check for the -affirm arg pattern:

# python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

# e.g. args[0] is '-affirm' and args[1] is 'Bart'

if len(args) == 2 and args[0] == '-affirm':

print_affirm(args[1])

Slide 45

Exercise 2: Make -hello Work

Write if-logic in main() to looking for the following command line form, call print_hello(name), passing in correct string.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -hello Bart

Solution code

if len(args) == 2 and args[0] == '-hello':

print_hello(args[1])

Slide 46

Exercise 3 (optional): Make -n Work

In this case, the function to call is print_n_copies(n, name), where n

is an int param, and name is the name to print. Note that the command

line args are all strings.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -n 10000 Hermione