Slide 1

Today - interpreter, math int/float, style, black box examples, boolean logic, string introduction, string +=, string for/i/range loop

Slide 2

The Python Interpreter

Examples below use the Python interpreter >>> to type expressions into Python, see what they do. You can access the interpreter using the Hack Mode button on the experimental server, or within PyCharm, the "Python Console" tab at the lower left.

In the interpreter, you type code at the >>> prompt, Python evaluates it, printing any result on the next line.

>>> 1 + 1

2

>>>

You will learn many parts of Python by seeing those feature explained in class. For some cases, you can also learn what Python does by typing an example into the interpreter to see what it does. This is a nice technique in lecture to show what various Python features do.

For more details, see the guide Python Interpreter

Slide 3

Two Math Systems - int and float

You would think computer code has a lot to do with numbers, and here we are.

See in Python reference: Python Math

Surprisingly, computer code generally uses two different types of numbers - "int" and "float".

Slide 4

int numbers

- The formal type "int" stores an integer

- e.g.

5, 23, -6 - There is no decimal-point dot in an int

e.g.3.14is not an int - int mathematics is precise and repeatable

3 + 4is exactly75 + 2is also exactly7- Math with int inputs .. produces int results

Except with division /

>>> 1 + 2

3

>>>

Slide 5

Use of ints - Indexing

- "Indexing" is accessing an element inside something

- Ints are naturally used for indexing

- e.g. image.get_pixel(x, y)

x y numbers like 0 1 2 .. - There is no pixel at x = 2.5

- Using a float here raises an error

Slide 6

float numbers

- float

3.14, 1.2e23 - float has a dot "." when printed

- Surprisingly, float is not totally precise (later topic)

- A float value in a computation forces the whole thing float

- Even if the answer comes out even, a float input makes a float output

>>> 1.5 + 1.5

3.0

>>>

>>> 1.0 + 2.0

3.0

>>>

You do have to be careful with floats, particularly when comparing them:

>>> 0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3

False

>>> 0.1 + 0.2

0.30000000000000004

>>> 0.3

What is going on here?? This is something you will cover if you eventually take CS107!

Slide 7

Math Operators: + - * / **

- int and float support the usual operators

+ - * / - Extra operator:

**is exponentiation - Precedence:

* /go before+ - - Otherwise evaluation goes left-right

- Fine to add parenthesis to force the order you want

- int-inputs → int-outputs, except / below

- Python int values do not have a fixed "max"

Most languages have an int max - Interpreter: use the up-arrow to edit previous lines - pro tip!

>>> 2 + 3

5

>>> 2 + 3 * 4 # Precedence

14

>>> 2 * (1 + 2) # Use parenthesis

6

>>> 10 ** 2 # 10 Squared

100

>>> 2 ** 100 # Grains of sand in universe

1267650600228229401496703205376

>>>

>>>

>>> 1 + 2 + 3

6

>>> 1 + 2.0 + 3 # Makes result float

6.0

Slide 8

Division / → float

- Division is tricky

a / breturns a float value always- Even if the division comes out even

- What if we want an int?

>>> 7 / 2

3.5

>>> 8 / 2

4.0

Slide 9

Int Division // → int

- This is a good idea from Python -

Have a formal "does int division operator" a // bint division operator- Rounds answer down to an integer, aka discards the remainder

- int inputs, always produces int output

- e.g. Compute width of a half sized image:

image.width // 2

Say image.width is 101

Want half size width of 50 pixels, not 50.5 - We'll mention // again later when we need to use it

>>> 7 // 2

3

>>> 8 // 2

4

>>> 102 // 4

25

Slide 10

Big Picture Strategy - Divide and Conquer

- Q: What is the main technique for solving big problems?

- A: Divide and Conquer

- Divide the big program into functions

- Work on one function at a time

- aka decomposition

- As we build up CS techniques ...

Many techniques are in service of the big-picture goal

Slide 11

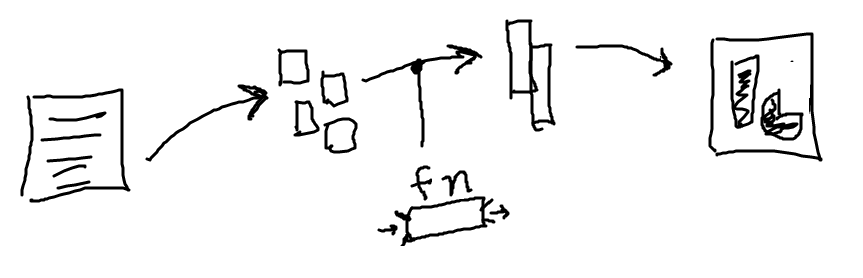

Data Flow Picture

Here is a way of looking at a program.

You have some files with data in them. You write code to lode the data into Python in one form. Then compute a transform into another form. Then a further computation produces an "answer" form. You publish the answer and get tweets of praise - the coding lifecycle! You can think of this as a sort of "data flow", from the original data to the final output.

Slide 12

Today: Black Box Function

- We have seen functions thus far, mainly we call them to run their code

- Today we will start using functions as data flow

- Each function is like a little box of some computation, with data-in and data-out

- One stage in the picture above might be one function

Slide 13

"Black Box" Function Model

Black-box model of a function: function runs with parameters as input, returns a value. All the complexity of its code is sealed inside.

The black box model makes it easy to call the function - provide data you have as the input, call the function, get back an answer.

Slide 14

Strategy - One Function at a Time

For Divide and Conquer, want to be able to work on each function separately, one at a time. We need to keep the functions sealed off from each other as much as possible. The black box model works well for this, narrowing the interactions to just the input and output data for each function.

Slide 15

Write Black Box Code - Cases

Here we'll work through the code for first black-box examples. There are in the logic 1 section on the experimental server.

Think of each input as a "case" the function must handle, return the correct output. To be correct, code needs to handle all the possible input cases. One hallmark of putting something on the computer is that it forces you to think through all the cases.

Slide 16

1. winnings1() Example

- This is a first, simple example

- Say we are writing a function for a lottery game

- Rules: input is an int score 0..10 inclusive

score 5 or more, winnings is score * 12

score 4 or less, winnings is score * 10 - We could make a table showing output for each input

- Code needs to work for all cases, i.e. "general"

- Later: we'll see how to put in formal tests that the code is getting the right output for each input

score winnings

0 0

1 10

2 20

3 30

4 40

5 60 # 12x kicks in here

6 72

7 84

8 96

9 108

10 120

Slide 17

1. Function Input = Parameter

def winnings1(score):

...

- The parameters to a function are its inputs

Left side of black-box picture - e.g.

scoreis the input here - Each is like a variable with a value in it

- Who put the value in the parameter?

The code that called this function - Code inside the function assume the parameter is set properly

Slide 18

2. Function Output = return score * 10

def winnings1(score):

return score * 10

- When a

returnline runs in a function- It exits the run of the function immediately

- It specifies the return value that will go back to the caller

- So the return statement determines the output of the function

Slide 19

Experiment 1 - winnings1()

You can type these in and hit the Run button as we go. The results are pretty easy to follow.

def winnings1(score):

return score * 10

- Try 1 line for the function:

return score * 10 - Look at the table of output

- See the basic role of parameter/return

- But this output is wrong half the time

Slide 20

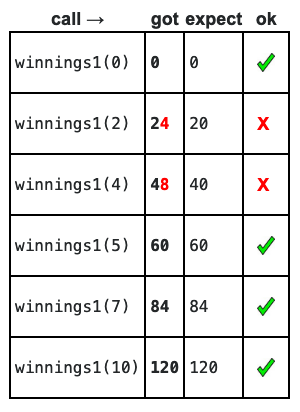

Experimental Server Output Format

def winnings1(score):

return score * 12

- Run function on experimental server, generates table of outputs

- It calls the function many times, shows the results one per row

- First "call" column is the input

- Second "got" column is what the function returned

- Easy to see the function's behavior this way

Slide 21

if-return Pick-Off Strategy

- The function needs to handle all possible input cases

- If-logic detects one case

Returns the answer for that case

Exiting the function - Lines below have if-return logic for other cases

- Code is "picking off" the cases one by one

- As we get past if-checks .. input must be a remaining case

- Analogy: coin sorting machine

Coin rolls past holes, smallest to largest

1st hole dime, 2nd hole penny, 3rd nickel, 4th quarter

A dime never makes it to the quarter-hole

The dime is picked-off earlier

Slide 22

Experiment 2

def winnings1(score):

if score >= 5:

return score * 12

Add if-logic to pick off the >= 5 case. It's only right half the time.

Slide 23

None Result

Noneis the default return value of a functionNoneis returned if there is no explicit return value- Possibly by "falling off the end" of the function

All its lines have run and the function is finished - Above example, we see

Noneif score < 5 - If you see

Nonelike this

Somehow your code is not explicitly returning a value

Slide 24

Experiment 3 - Very Close

def winnings1(score):

if score >= 5:

return score * 12

if score < 5:

return score * 10

Add pick-off code for the score < 5 case. This code returns the right

result in all cases. There is just at tiny logical flaw.

Slide 25

Experiment 4 - Perfect

def winnings1(score):

if score >= 5:

return score * 12

# If we get to this line, score < 5

return score * 10

- Each pick-off recognizes a case and exits the function

- Therefore for lines below, the picked-off case is excluded

- That is, the

score < 5test is unnecessary - Coding strategy - helps your one-at-a-time attention

Work on code for case-1

When that's done, put it out of mind

Work on case-2, knowing case-1 is out of the picture

Slide 26

winnings1() Observations

- Thinking about cases, if-logic to pick them off one at a time

- Try changing <= to <

- A form of Off By One bug - be careful right at the boundary

- What about this form...

def winnings1(score):

if score >= 5:

return score * 12

return score * 10

That does not work. The second return is in the control of the if. It never runs because the line above exits the function. In Python code, where a line is indented is very significant.

Slide 27

2. Winnings2 Example

Extra practice example.

Say there are 3 cases. Use a series of if-return to pick them off. Need to think about the order. Need to put the == 10 case early.

Winnings2: The int score number in the range 0..10 inclusive. Bonus! if score is 10 exactly, winnings is score * 15. If score is between 4 and 9 inclusive, winnings is score * 12. if score is 3 or less, winnings is score * 10. Given int score, compute and return the winnings.

Solution

def winnings2(score):

if score == 10:

return score * 15

if score >= 4: # score <= 9 is implicit

return score * 12

# All score >= 4 cases have been picked off.

# so score < 4 here.

return score * 10

Slide 28

Boolean Values

For more detail, see guide Python Boolean

- "boolean" value in code -

TrueorFalse - if-test and while-test work with boolean inputs

- e.g.

bit.front_clear()returns a boolean - So we have

if bit.front_clear():

Slide 29

Ways to Get a Boolean

==operator to compare two things

2 == 1 + 1returnsTrue

Two equal signs

Since single=is used for var assignment!=- not-equal test

2 != 10returnsTrue- Compare greater-than / less-than

<is strict less-than<=is less-or-equal to- These all work with ints, floats, other types of data

Try this in the interpreter (or Hack Mode button at bottom experimental server)

>>> n = 5 # assign to n to start

>>> n == 6

False

>>> n == 5

True

>>> n != 6

True

>>>

>>> n < 10

True

>>> n < 5 # < is strict

False

>>>

>>> n <= 5 # less-or-equal

True

>>>

>>> n > 0

True

Slide 30

Boolean Operators: and or not

- An operator combines values, returning a new value

e.g.+operator,1 + 2returns3 - Boolean operators combine

True Falsevalues - Boolean operators:

and or not - Suppose here that

xxxandyyyare boolean values xxx and yyy- if both sides areTrue, then it isTrue

aka all the inputs must be Truexxx or yyy- if either side or both sides areTrue, it isTrue

aka some input must be Truenot xxx= invertsTrue/False

Why doesnotgo to the left?

It's like the-for a negative number

e.g.-6

Slide 31

Weather Examples - and or not

Say we have temp variable is a temperature, and is_raining is a

Boolean indicating if it's raining or not. Here are some examples to

demonstrate and or not:

# OR: either or both are true

# Say we don't want to go outside if

# if it's cold or raining.

if temp < 50 or is_raining:

print('not going outside!')

# AND

# We want to go outside if it's snowing.

if temp < 32 and is_raining:

print('yay snow!')

# AND + NOT

# Sunny and nice case:

if temp > 70 and not is_raining:

print('Sunny and nice!')

# Style note: don't use == False or == True

# to form a test. See above how "is_raining"

# is used directly in the test, or with a "not"

# in front of it.

Slide 32

Numeric and Example

Suppose we have this code, and n holds an int value.

if n > 0 and n < 10:

# get here if test is True

What must n be inside the if-statement? Try values like 0 1 2 3 . 8 9 10

You can work out that n must be a an int value in the range 1..9 inclusive.

Slide 33

3. is_teen(n) Example

is_teen(n): Given an int n which is 0 or more. Return True if n is a "teenager", in the range 13..19 inclusive. Otherwise return False. Write a boolean test to pick off the teenager case.

Solution

def is_teen(n):

# Use and to check

if n >= 13 and n <= 19:

return True

return False

# Future topic: possible to write this

# as one-liner: return n >= 13 and n <= 19

Slide 34

4. Lottery Scratcher Example

An extra example for practice.

Lottery scratcher game: We have three icons called a, b, and c. Each is an int in the range 0..10 inclusive. If all three are the same, winnings is 100. Otherwise if 2 are the same, winnings is 50. Otherwise winnings is 0. Given a, b and c inputs, compute and return the winnings. Use and/or/== to make the tests.

Solution:

def scratcher(a, b, c):

# 1. All 3 the same

if a == b and b == c:

return 100

# 2. Pair the same (3 same picked off above)

if a == b or b == c or a == c:

return 50

# 3. Run gets to here, nothing matched

return 0