Slide 1

Today: variables, digital images, RGB color, for loop

Slide 2

Announcements

- Bryant, a Section Leader, will be leading weekly Extra Practice Sessions from 2-3PM on Mondays for CS106A, which will be an unofficial, "lite" version of ACE this summer.

- More information here.

- If you are interested, please fill out this form by this Wednesday: https://tinyurl.com/extrapracticecs106.

- Assignment 1 is due tomorrow (Tuesday) at midnight. Assignment 2 will be released tomorrow, as well.

Slide 3

PSA - What is "done" for a homework?

- Tempting: well the output is right, so I'm done!

Turn it in quick! - You should understand why every line is there

- e.g. suppose you deleted all your code

How long would it take to re-do it?

Ideally, not long, since you've learned it - The quiz problems will look a lot like the HW problems

Slide 4

Real Life Sequence of a Computer Project

- Think of a goal in the real world

- Sketch out an algorithm for it

- Having a rough algorithm idea is one thing

- You need to figure out every detail to write code for it

i.e. to be able to explain it to a computer

"Science is what we understand well enough to explain to a computer. Art is everything else we do." - Donald Knuth, CS legend and Stanford CS Professor emeritus

Slide 5

Variables - Two Things To Know

More details later here: Python Variables section in the guide.

A Python variable has a name and stores a value. We'll start with two rules of variables.

1. Creating a Variable

A variable is created in the code by a single equal sign, like this: =, which creates a variable named x:

...

x = 42

...

The variable is set at the moment the line runs.

As a drawing, think of the variable as a little box, labeled with the variable's name, containing a pointer to the value stored.

2. Reading a Variable

After a variable is created, its name can appear in the code, e.g. x, and that use follows the arrow, retrieving whatever value was stored earlier. The name appears in the code as a bare word, no quote marks or anything.

Here's a little example. Suppose we set a variable named color to

hold the value 'red'. Then subsequent lines can use color, and that

retrieves the stored color.

color = 'red'

# instead of bit.paint('red')...

bit.paint(color)

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)

This paints 2 squares 'red', or whatever value was assigned to color on the first line.

Slide 6

Try It - All Blue

> all-blue

Go back to our all-blue Bit loop. Change the code to use a color

variable as below. The variable color is set to hold the value

'blue', and the later lines just paint whatever color is in the

color variable. This version paints the whole row blue.

def all_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

color = 'blue'

bit.paint(color)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint(color)

bit.right()

Look at the lines bit.paint(color) lines - they refer to the variable

by its name, following the arrow to retrieve 'blue' or whatever was

stored there.

Q: How would you change this code to paint the whole row red?

A: Change line 3 to color = 'red' - the later lines just use whatever

is in the color variable, so now they will paint red with no other

change.

Slide 7

Interpreter / Hack Mode

Try the >>> Hack Interpreter - there's a button for this at the bottom of each problem page. You type a little expression at the ">>>" prompt and hit the enter key. Python evaluates it, prints the resulting value on the next line. We'll use this more as we get into more Python features.

>>> 1 + 1

2

>>> 1 + 2 * 3

7

In that second example, see that Python follows the order of operations in an expression - evaluate multiplication and division before addition and subtraction.

Slide 8

Interpreter - Variable Demo

Suppose we want to compute the number of hours in a week. Then try

defining a days variable using ={.b}...

>>> 7 * 24

168

>>> days = 7

>>> days * 24

168

>>> # Can assign a new value to variable, overwrites old value

>>> days = 365

>>> days * 24

8760

Shows setting a variable with =. Any existing value in the variable is

overwritten by the new value. Using that variable name later retrieves

the most recent stored value.

Slide 9

Images - Numbers - Code

- Layers of understanding

- See An image

- Understand structure of numbers, red/green/blue etc. making an image

- Write code to change the numbers, changing the image – this is programming!

- We'll look at all of these today

Slide 10

Digital Images - Pixels

- Originally the internet was made of text

- But perhaps images is where it really shines

- Digital images are made of small square "pixels"

"picture element" - "pixel" - Pixel = small, square, shows a single color

- The color of a pixel is very often encoded as RGB

- Demo: Open pebbles.jpg in Mac Preview

Preview feature: new-from-clipboard to open copied image

It can zoom in far to see the pixels

Unzoomed:

See pebbles-zoomed.png:

Slide 11

RGB Color Scheme

- The red-green-blue scheme, RGB

- The color is defined by three numbers: red, green, and blue

- Each number in the range 0..255

- (Why 255? I'll explain later)

- Each number represents a brightness of red/green/blue lights

- 0 = light is off

- 255 = light at maximum

- Can mix these 3 lights to make any color!

- Define any color by 3 numbers, 0..255

- Live RGB explorer: rgb explorer

- Note: the RGB light-mixing scheme different from paint-mixing scheme

Slide 12

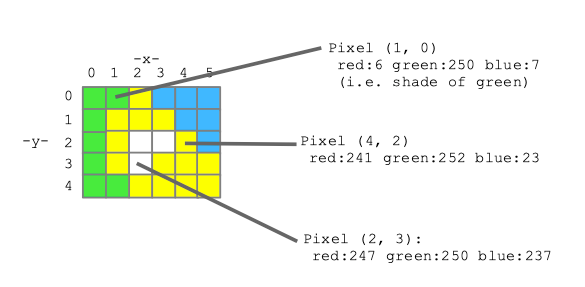

Image Code - Pixels, Coordinates, RGB

- Image is made of pixels

- Pixels are in a x,y coordinate scheme

- Origin (0, 0) at the upper left

Origin at the upper left feels a little weird at first

Super common system on computers

We'll use it all quarter - x numbers:

x=0is left edge

x values grow going to the right - y numbers:

y=0is the top row

y values grow going down - Each pixel:

- Small

- Square

- Shows one color

- Pixel's color is encoded as 3 RGB numbers

Slide 13

Image Made of Pixels

Slide 14

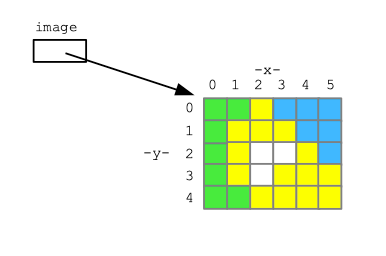

Image Loading Code

This line loads an image into Python memory, and sets a variable named

image to point to it, ready for Python to work on it.

# Load an image from the filesystem

# into memory in variable named "image".

# Now the image can be manipulated by code.

image = SimpleImage('flowers.jpg')

Slide 15

Have an Image, How To Change it?

Say we have loaded an image variable as shown above. Now we want to

write code to change the image in some way.

For example, let's say we want to set the blue and green values in each pixel of the image to 0. This will leave just the red values. This is called the "red channel" of the image - an image made of just its red lights.

Slide 16

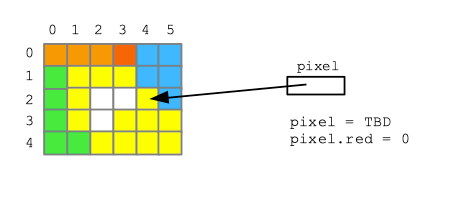

Preamble: pixel.red = 0

Suppose we had a variable pixel that referred to one pixel inside an

image. (We'll show how to obtain such a pixel variable in the next

step.)

Then the syntax pixel.red or pixel.blue or pixel.green refers to

the red or blue or green value 0..255 inside the pixel.

The code below sets the red value of the pixel to 0, using the =

similarly to above.

pixel.red = 0

Slide 17

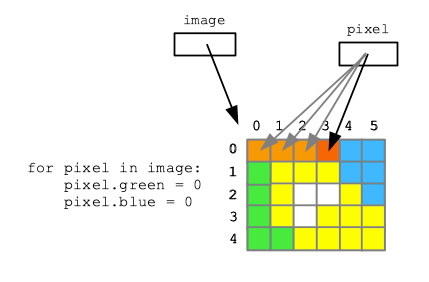

The Solution - for loop

Here is the code that solves it using a "for loop", and we'll look at how it works.

def red_channel(filename):

image = SimpleImage(filename)

for pixel in image:

pixel.green = 0

pixel.blue = 0

return image

Here is a link - you can try running it first, then we'll see how it works

Slide 18

How It Works - Big Picture

For loop syntax:

for variable in collection:

# use variable in here

- The for loop is probably the most useful loop

- The for loop runs over a collection of elements

- Runs the loop body once for each element

- For each iteration, variable is set to point to one element from the collection

- Called the "for each" loop - running once for each element

- In this case, the loop body runs once for each pixel

- The variable name, e.g. pixel, can be any name the programmer chooses

Slide 19

Image Foreach Operation

Slide 20

Image Foreach Observations

- Filename is like 'flowers.jpg'

image = SimpleImage(filename)

loads image data into memoryimageis a variable, points to image datafor pixel in image:

Loop runs lines once for each pixel in image

pixelvariable points to each pixel in turnreturn image

return xxxreturns a value back to our caller, more on that later- How many times does first line run? How many times do the lines

in the loop?

- The first line runs once for each pixel

- So if there are 50,000 pixels, the loop body is run 50,000 times

- Experiment: green channel, make every pixel black

- See how for loop runs over the image

- See how

pixel.____accesses red/green/blue numbers

Slide 21

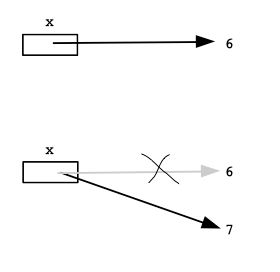

Update Variable: x = x + 1

What does this do:

x = x + 1

- Update the value of a variable

- It is not a mathematical expression, it is setting the value of

x

- It is not a mathematical expression, it is setting the value of

- Variable is on both left and right of =

- This changes the variable in a relative way. The original value of

xis used to redefine the new value ofx(to be exactly one more than the original value)

- This changes the variable in a relative way. The original value of

- Code rule:

- first "evaluate" right side expression, after the =

- assign that value back into the variable

- So x is 7 at the end

x = 6

x = x + 1

Slide 22

image1-b. Make Image Darker

- Try making values smaller, image gets darker

e.g. red 200, change to red 100: the image literally gets darker - `pixel.red = pixel.red / 2'

- Relative change of red/green/blue on each pixel

- See below about "shorthand", re-write with *=

for pixel in image:

pixel.red = pixel.red / 2

pixel.green = pixel.green / 2

pixel.blue = pixel.blue / 2

# or shorthand form:

# pixel.red /= 2

Slide 23

Relative Variable Shorthand: +=, -=, *=

Shorthand way to write x = x + 1

x += 1

Shorthand for x = x * 2

x *= 2 # double x

- Works for all operators, such as

+= -= *= /= - Handy because relative math on a variable is very common

- This just make the code more compact, not changing the underlying math

>>> x = 10

>>> x += 3

>>> x

13

>>> x *= 2

>>> x

26

Note: if you are used to x++ from other programming languages (C, C++, Javascript, etc.), Python does not have this syntax. You must either use x = x + 1 or x += 1.

Slide 24

Image2 Puzzles

- Loop over image, write code to change pixels - "foreach" loop

- recover hidden image

- 5-10-20 puzzle

5-10-20 puzzle: red, green, and blue values are too small by a factor of 5 10 20. But we do not know which factor goes with which color. Figure it out by experimenting with code to modify the image with various factors. - copper puzzle

Slide 25

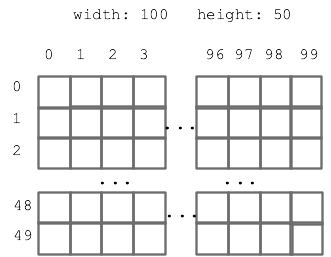

Image Coordinate System

Previously loaded image into memory like this. Now look at the x/y coordinate scheme of the pixels.

image = SimpleImage(filename)

image.width,image.height- int number of pixels

e.g. image.width is 200, image.height is 100

(like pixel.red - these are Python "properties")- Origin

x=0y=0is at upper left- x grows right

- y grows down

- This coordinate scheme is like typesetting lines of text

- Zero based indexing

First element is index 0 - If the width is 100, what is the rightmost pixel's x value

- it's not 100! it's 99\

- Super common mistake in zero-based world

- width 100, height 50 drawing, (x, y) pixels:

(0, 0) pixel at upper left

(99,0) at upper right

(99, 49) at lower right - These x,y values are all fundamentally int numbers

There's no pixel atx=2.5

Using a float value (i.e., a number with a decimal point) to address an x,y will fail with an error

We will talk about float values later

Slide 26

image.get_pixel(x, y)

- An image function that accesses one pixel

image.get_pixel(x, y)- Returns a reference to the pixel at

x, y - Store reference in a variable, use

.red.greenon it - Typically we use "pixel" as the variable name for this

# For the pixel at x=4 y=2 in "image",

# set its red value to 0

pixel = image.get_pixel(4, 2)

pixel.red = 0

![]()

Slide 27

Goal: Loop Over All the Coordinates

Step 1: range() function

Slide 28

for x in range(10):

- Today: want to write a loop where x = 0, 1, 2, 3, ...99

- 1-parameter range(n) function

range(10)represents the series:

0, 1, 2, ... 8, 9- Start at 0, go up to but not including the n parameter

range(10)= 0, 1, 2, .. 9range(5)= 0, 1, 2, 3, 4range(n)= 0, 1, ... n-1range(n)works in a foreach loop- Works well with zero-based indexing

Slide 29

Hack/Demo: Try In Interpreter

Demo (or you can try it). The print(x) function in this context just prints out what is passed to it within the parenthesis.

>>> for x in range(10):

print(x)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>>

So here, we can see that foreach works with range, running the body once for each element.

Slide 30

Generating all x,y numbers for an image

- Say image width is 100, height is 50

- Basic plan to use range() to generate all x,y numbers

for x in range(image.width):

x will range over 0, 1, 2, .. 99for y in range(image.height):

y will range over 0, 1, 2, .. 49

Slide 31

Nested Loops

- Nested loops are a little advanced

- Each run the loop body is called an "iteration" of the loop

- What happens if we place a loop inside another?

- An "outer" loop

- An "inner" loop

- Try it in this example

Slide 32

Nested in Interpreter

- e.g. image 5 wide, 4 high

- Outer loop runs through the y values: 0, 1, 2, 3

- Inner loop runs through the x values: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

- Rule: for 1 iteration of outer, get all the iterations of the inner

e.g. y = 0, all the x's

then y = 1, all the x's again - Can type it into the interpreter, see the nesting in action

>>> for y in range(4):

for x in range(5):

print('x:', x, 'y:', y)

x: 0 y: 0

x: 1 y: 0

x: 2 y: 0

x: 3 y: 0

x: 4 y: 0

x: 0 y: 1

x: 1 y: 1

x: 2 y: 1

x: 3 y: 1

x: 4 y: 1

x: 0 y: 2

x: 1 y: 2

x: 2 y: 2

x: 3 y: 2

x: 4 y: 2

x: 0 y: 3

x: 1 y: 3

x: 2 y: 3

x: 3 y: 3

x: 4 y: 3

Slide 33

Example: Darker-Nested

Here is a version of the previous darker algorithm, but written using nested range()

def darker(filename):

"""

Darker-image algorithm, modifying

and returning the original image.

This version uses nested range loops.

Demo - this code is complete.

"""

image = SimpleImage(filename)

for y in range(image.height):

for x in range(image.width):

pixel = image.get_pixel(x, y)

pixel.red *= 0.5

pixel.green *= 0.5

pixel.blue *= 0.5

return image

- Use nested y/x loops to hit every pixel in an image

- Nested loop sequence:

- 1. Outer loop does first iteration, e.g. y = 0

- 2. Inner loop does all its iterations, x = 0, 1, 2, 3 ...

This gives us all y=0 coords: (0, 0), (1, 0), (2, 0), .. (99, 0) - 3. Outer loop does second iteration, y = 1

- 4. Inner loop does all iterations again: x = 0, 1, 2, 3 ...

This gives us all y=1 coords: (0, 1), (1, 1), (2, 1), .. (99, 1) - The effect is going through the rows top to bottom. Each row going left to right - like reading English text

- Demo: add in inner loop:

print('x:', x, 'y:', y)

print() like this is a debugging trick we'll build on later

See a line printed for each pixel, showing the whole x,y sequence

Only do this with small images like we have here

Otherwise it's too much output - Demo: try making x too limited,

range(image.width - 20) - Demo: what if we swap the roles of the y/x loops?

It works fine, just a different order of the pixels

Goes through the columns left-right. For each column, top to bottom

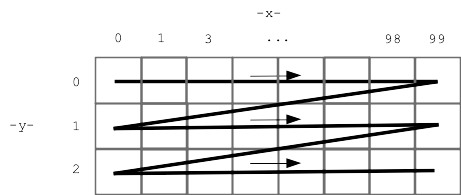

Here is a picture, showing the order the nested y/x loops go through all the pixels - all of the top y=0 row, then the next y=1 row, and so on.

Good news: this is our first nested loop. We'll do more later. It happens that the y/x nested loop for an image is idiomatic - it's the same every time, so you can just kind of use it while you get used to it.