What can we draw, perfectly?

Neil Rathi // Math 120, Fall 2023

I am not very good at drawing. My lack of basic artistic competence means that I'm limited to whatever can be sketched with the crutch of a couple basic tools.

Fortunately, I share this predicament with the brightest mathematicians of Ancient Greece. Pythagoras and Euclid had a preoccupation with the ruler and compass, tools which allow us to construct geometries of perfect precision. This was born out of an insistence that the world could be perfectly mathematically constructed. Euclid's Elements spell this out in the first three of his five geometric postulates:

- A straight line is defined by two distinct points

- Any straight line can be extended infinitely

- A circle is defined by two distinct points (a center and a point on the circumference)

These postulates define a 'perfect' infinite ruler (1 and 2) and a 'perfect' compass (3), forming the basis of Euclidean geometry. See, we can't be sure that any by-hand sketch is 100% accurate. But anything that solely uses the Euclidean ruler-and-compass is necessarily mathematically perfect: parallel lines are perfectly parallel, angle bisectors bisect unblemished.

So then, what can Pythagoras (and I) draw? The Greeks were prolific constructors, with recipes to draw anything from tangent lines to regular polygons. Three problems, however, continued to stump them:

- Given an angle, is there a recipe to construct an angle with one third the measure?

- Given a cube, is there a recipe to construct a cube with double the volume?

- Given a circle, is there a recipe to construct a square with the same area?

We refer to these as trisecting the angle, doubling the cube, and squaring the circle. The Greeks (and other civilizations) tried endlessly to build these three constructions, convinced that they were possible. Indeed, it was not until the 19th century that we had a definite proof of their impossibility, due to Wantzel.

It turns out that this impossibility is tied to the notion of algebraic fields [1]. In what follows, we prove that the first two of these problems are impossible (squaring the circle is more challenging, but follows a similar line of reasoning). Effectively, our proof boils down to first showing that only a certain subset of the real numbers \(\R\) can be constructed, and then showing that the solutions to the problems do not fall within this subset.

Part 1: What numbers can I construct?

Euclid's Elements give us a nice framework for examining constructibility. Note that if we accept the Euclidean version of a perfect straightedge and compass, we are limiting ourselves to the following five 'operations' on points:

- Creating a line from two distinct points

- Creating a circle from two distinct points

- Finding the intersection of two distinct lines

- Finding the intersection(s) of two distinct circles

- Finding the intersection(s) of a line and a circle

This gives us a nice way to formulate constructibility.

Figure 1. Operations with straightedge-and-compass.

The issue is that this definition of constructibility doesn't allow us to say if some arbitrary point is constructible. To that end, it would be useful to have an algebraic characterization of the constructible numbers. To make things slightly more formal, let's consider points \((x,y) \in \R^2\), and define \(K \times K \subseteq \R^2\) as the set of konstructible points. Assume that we start constructing at the "origin" \((0, 0)\). Which elements of \(\R\) are also elements of \(K\)?

We can draw out some arbitrary length with our straightedge; let's call this length \(1\). We can copy \(1\) with our compass, and shift this over infinitely in the cardinal directions, giving us the perpendicular \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes of the Cartesian plane. This allows us to construct any of the integers using \(1\) through basic addition and subtraction (more formally, this is because \(\Z\) is cyclic and generated by \(1\)). So then \(\Z \subseteq K\).

Figure 2. Construction of \((x,y) \in \Z \times \Z\)

If we have lengths \(a, b\) which are constructed in this way, we can then create \(a + b, a - b, a \cdot b,\) and \(a/b\). The first two can be straightforwardly constructed by appending the two lengths together. We show multiplication geometrically in Figure 3 (division is the same, replacing the length \(ab\) with \(a\)). So then \(\mathbb{Q} \subseteq K\).

Figure 3. Construction of \(a\cdot b\)

Figure 4. Construction of \(\sqrt{a}\)

If we have a length \(a\), we can use \(1\) to construct \(\sqrt{a}\) geometrically as in Figure 4. This is a result of the Pythagorean theorem; if we let \(x\) be the relevant altitude of the triangle, we have

$$ \begin{aligned} \left(\sqrt{x^2 + 1}\right)^2 + \left(\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}\right)^2 &= (a + 1)^2 \\ x^2 + 1 + a^2 + x^2 &= a^2 + 2a + 1 \\ 2x^2 &= 2a, \end{aligned} $$so \(x = \sqrt{a}\). So \(K\) includes all numbers which can be made from the integers with addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square roots (note that this includes nested square roots).

It turns out that this is all of \(K\). We cannot construct, for example, transcendental numbers, or cube roots of arbitrary rationals (a point that is relevant for the proofs we cover below). To see this, we start with the numbers in the subset of \(K\) we found above and ask if our five basic operations can produce any other points.

Note that creating a line or a circle on their own (e.g. the first two operations) won't allow us to find any new points. We can, however, use these operations together to identify intersections.

If we create a line, this obviously limits us to the \((x,y) \in K\) we identified earlier. But if we create a second line that intersects this, we can describe their intersection as the solution to $$\begin{cases} a_0x + b_0y = c_1 \\ a_1x + b_1y = c_2, \end{cases}$$ with \(a, b, c\) rational/square roots. Of course, the solution to a system of linear equations can always be found via Gaussian elimination, which simply uses addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. That is, the intersection of any two lines with rational and square root coefficients will also always have a rational and square root closed-form expression.

Alternatively, we can construct a circle (which is again limited to the subset we found above), and then draw a line that intersects this. The point of intersection here is the solution to the system $$\begin{cases} (x-a_0)^2 + (y-b_0)^2 = r_0^2 \\ a_1x + b_1y = c_2. \end{cases}$$

We can solve this through, for example, substitution:

$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{b_1} \left(c_2 - a_1x\right) &= y \\ (x-a_0)^2 + \left(\frac{1}{b_1} \left(c_2 - a_1x\right)-b_0\right)^2 &= r_0^2. \end{aligned} $$This is a quadratic in \(x\), which has solutions of the form $$x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{a^2 - 4ac}}{2a}.$$ But here, the coefficients \(a,b,c\) are rational/square root, meaning that \(x\) is also rational/square root. Similarly, consider the intersection of two distinct circles, which is the solution to

$$\begin{cases} (x-a_0)^2 + (y-b_0)^2 = r_0^2 \\ (x-a_1)^2 + (y-b_1)^2 = r_1^2. \end{cases}$$Subtracting and rearranging yields $$2(a_1 - a_0) \cdot x + 2(b_1 - b_0) \cdot y = a_1^2 - a_0^2 + b_1^2 - b_0^2 + r_0^2 - r_1^2$$ which is a linear equation in \(x,y\). Then we have a system of a circle and a line, which reduces to the case above, so the solution to this system must be constructible as well.

We've therefore shown that any point that all constructible numbers can be expressed in closed form through integers with addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square roots, and all such numbers are constructible. This gives us the full formulation of \(K\).

As we showed above, this also means that \(\Z \subseteq \mathbb{Q} \subseteq K\) (but \(K\) also includes irrationals, like \(\sqrt{2}\). The impossibility of trisecting the angle and doubling the cube directly follows from this algebraic characterization of \(K\), which we now show.

Part 2: Why can't I trisect an angle?

The classical formulation of angle trisection asks us for a generic recipe that works for any angle. So to prove that this recipe does not exist, we just need to show one angle for which the construction is impossible: consider \(\theta = 60^{\circ}\). We want to construct an angle of exactly one-third this measure, i.e. \(20^{\circ}\).

Figure 5. Constructing \(\cos\theta\) from \(\theta\).

Figure 6. Constructing \(\theta\) from \(\cos\theta\).

You might ask why we've done all of this work to develop \(K\) algebraically. Note that if we can construct \(\theta\), we can also construct \(\cos\theta\) by drawing a unit segment and dropping a perpendicular down (Figure 5). Then, we can use the triple angle identity:

$$ \cos \theta = 4 \cos^3 \left(\frac{\theta}{3}\right) - 3\cos \left(\frac{\theta}{3}\right). $$Letting \(\theta = 60^{\circ}\) and \(\cos(20^{\circ}) = x\), we have

$$ \frac{1}{2} = 4x^3 - 3x, $$which we transform into

$$ 8x^3 - 6x - 1 = 0. $$All we need to do is construct a segment of length \(x\), since this will allow us to straightforwardly construct an angle of measure \(20^{\circ}\) (see Figure 6). It turns out, however, that this equation has no solutions in \(K\), meaning that \(x\) (and thus \(20^{\circ}\)) is not constructible.

The proof of this claim is the bulk of our work. We rely on induction, first showing that the equation has no rational roots, and then iteratively extending the field of possible solutions with \(\sqrt{\gamma}\) for some \(\gamma\). For this first part, we show a more general statement about the rational roots of a polynomial.

- \(a_n\) is divisible by \(q\)

- \(a_0\) is divisible by \(p\)

This proof is straightforward. Let \(x = p/q\) be a root of \(f\) such that

$$ \begin{aligned} a_n\left(\frac{p}{q}\right)^n + a_{n-1}\left(\frac{p}{q}\right)^{n-1} + \cdots + a_0 &= 0 \\ a_np^n + a_{n-1}p^{n-1}q + \cdots + a_0q^n &= 0 \\ p(a_np^{n-1} + a_{n-1}p^{n-2}q + \cdots + a_1p^{n-1}) &= -a_0q^n, \end{aligned} $$so that \(p\) divides \(a_0s^n\). But \(\gcd(p, q) = \gcd(p, q^n) = 1\), meaning that \(p\) divides \(a_0\). Similarly, we have

$$ q(a_{n-1}p^{n-1} + a_{n-2}p^{n-2}q + \cdots + a_0q^{n-1}) = -a_np^n, $$so that \(q\) divides \(a_n\) as desired.

We can directly apply this result to \(p(x)\) above: the possible rational roots of \(8x^3 - 6x - 1\) are \(\left\{\pm 1, \pm \frac{1}{2}, \pm \frac{1}{4}, \pm \frac{1}{8}\right\}\), but after checking manually we note that none of these values are zeroes. Thus, \(8x^3 - 6x - 1 = 0\) has no rational solutions.

Now, we'll proceed by induction to show that \(p(x)\) has no constructible roots. See, since we know \(p(x)\) has no roots in \(\mathbb{Q}\), it's tempting to just tack on an extra square root—maybe the solution lies in \(\mathbb{Q}[\sqrt{\gamma}].\) And if we can't find roots here, maybe it has roots in \((\mathbb{Q}[\sqrt{\gamma}])[\sqrt{\gamma'}],\) and so on.

This method necessarily fails. In particular, we show that if \(p(x)\) has no solutions in a field \(\mathbb{F}\), then it has no solutions in \(\mathbb{F}[\sqrt{\gamma}]\). We work by contradiction: assume that \(p(x)\) does have a solution \(r_1\) in \(\mathbb{F}[\sqrt{\gamma}]\), which we can write as \(r_1 = a + b\sqrt{\gamma}\) for \(a,b,\gamma \in \mathbb{F}\). Then we can expand \(p(r_1)\) as

$$ \begin{align*} p(a+b\sqrt{\gamma}) &= 8(a + b\sqrt{\gamma})^3 - 6(a + b\sqrt{\gamma}) - 1 \\ &= 8(a^3 + 3a^2b\sqrt{\gamma} + 3ab^2\gamma + b^3\gamma\sqrt{\gamma}) - 6a - 6b\sqrt{\gamma} - 1. \end{align*} $$We can group these terms into those in \(\mathbb{F}\) and those in \(\mathbb{F}[\sqrt{\gamma}]\). Call these \(X\) and \(Y\sqrt{\gamma}\) respectively.

$$ (\underbrace{8a^3 + 24ab^2\gamma - 6a - 1}_{X}) + \sqrt{\gamma}(\underbrace{24a^2b + 8b^3\gamma - 6b}_{Y}) = 0. $$So then \(X = -Y\sqrt{\gamma}\). But we also know that \(X, Y \in \mathbb{F}\) but \(\sqrt{\gamma} \not \in \mathbb{F}\), so that means the only way for the equality to hold is for \(X = Y = 0\). Now, with this in mind consider \(p(a - b\sqrt{\gamma})\). We have

$$ \begin{align*} p(a-b\sqrt{\gamma}) &= 8(a - b\sqrt{\gamma})^3 - 6(a - b\sqrt{\gamma}) - 1 \\ &= 8(a^3 - 3a^2b\sqrt{\gamma} + 3ab^2\gamma - b^3\gamma\sqrt{\gamma}) - 6a + 6b\sqrt{\gamma} - 1 \\ &= (\underbrace{8a^3 + 24ab^2\gamma - 6a - 1}_{X}) - \sqrt{\gamma}(\underbrace{24a^2b + 8b^3\gamma - 6b}_{Y}). \end{align*} $$But since as above \(X = Y = 0\), we just have \(p(a-b\sqrt{\gamma}) = 0.\) This means that \(r_2 = a - b\sqrt{\gamma}\) is also a root of \(p(x)\).

Since \(p(x)\) is a cubic, we can uniquely factorize it in terms of its roots:

$$ p(x) = 8(x - r_1)(x - r_2)(x - r_3), $$where \(r_1 = a + b\sqrt{\gamma}\) and \(r_2 = a - b\sqrt{\gamma}\). This third root, \(r_3\), is still mysterious—until we expand our factorization of \(p\).

$$ p(x) = 8(x^n - (r_1 + r_2 + r_3)x^{n-1} + \dots - r_1r_2r_3) = 8x^3 - 0x^2 + 6x - 1, $$so that equating like terms yields \(r_1 + r_2 + r_3 = 0\). This very conveniently yields

$$ (a + b\sqrt{\gamma}) + (a - b\sqrt{\gamma}) + r_3 = 2a + r_3 = 0, $$so \(r_3 = -2a\). We also assumed \(a \in \mathbb{F}\), which means \(r_3\) is also in \(\mathbb{F}\). But, since we know \(p(x)\) has no roots in \(\mathbb{F},\) this is a contradiction! Thus, \(p(x)\) cannot have roots in \(\mathbb{F}[\sqrt{\gamma}]\) if it has no roots in \(\mathbb{F}\).

What we've done here is show that—since \(p\) has no rational solutions—we can't just endlessly extend the field with a square root to find zeroes. This implies that we can't find solutions to \(p\) in the field

$$ (((\mathbb{Q}[\sqrt{\gamma_1}])[\sqrt{\gamma_2}])[\sqrt{\gamma_3}])\dots $$But this field looks familiar: the rational numbers adjoined with square roots. Indeed, this is just our algebraic definition of \(K.\) So there is no way of geometrically constructing a segment of length \(x = \cos(20^{\circ})\). Thus, we can't construct a \(20^{\circ}\) angle, which means that it's impossible to trisect a \(60^{\circ}\) angle. And this, as we noted earlier, is enough to prove that there is no generic recipe to trisect any given angle.

Part 3: Why can't I double a cube or square a circle?

Our proof of the impossibility of trisection is a template that can be used to prove the other two impossibilities. Doubling the cube proves to be effectively equivalent to trisecting the angle: if we have a cube of volume \(1,\) we need to construct a new cube with side length \(x\) such that \(x^3 = 2,\) which we can straightforwardly show has no solutions in \(K\) (we leave details to the reader, but the proof roughly follows that of trisecting the angle).

Proving impossibility of squaring the circle turns out to involve a few extra steps beyond the scope of this paper. In essence, it boils down to constructing a segment of length \(\sqrt{\pi}\). But this is impossible because \(\pi\) is transcendental, and thus not the solution to any polynomial, so it cannot be algebraically constructed.

Conclusion: What if I really, really, really want to trisect an angle?

At the very beginning of this paper I laid down a set of axioms and bounded our capabilities within them. And there is good reason to use such axioms! But the Greek preoccupation with the compass and unmarked straightedge is restrictive, and if we allow ourselves some axiomatic flexibility, we can indeed trisect the angle or double the cube.

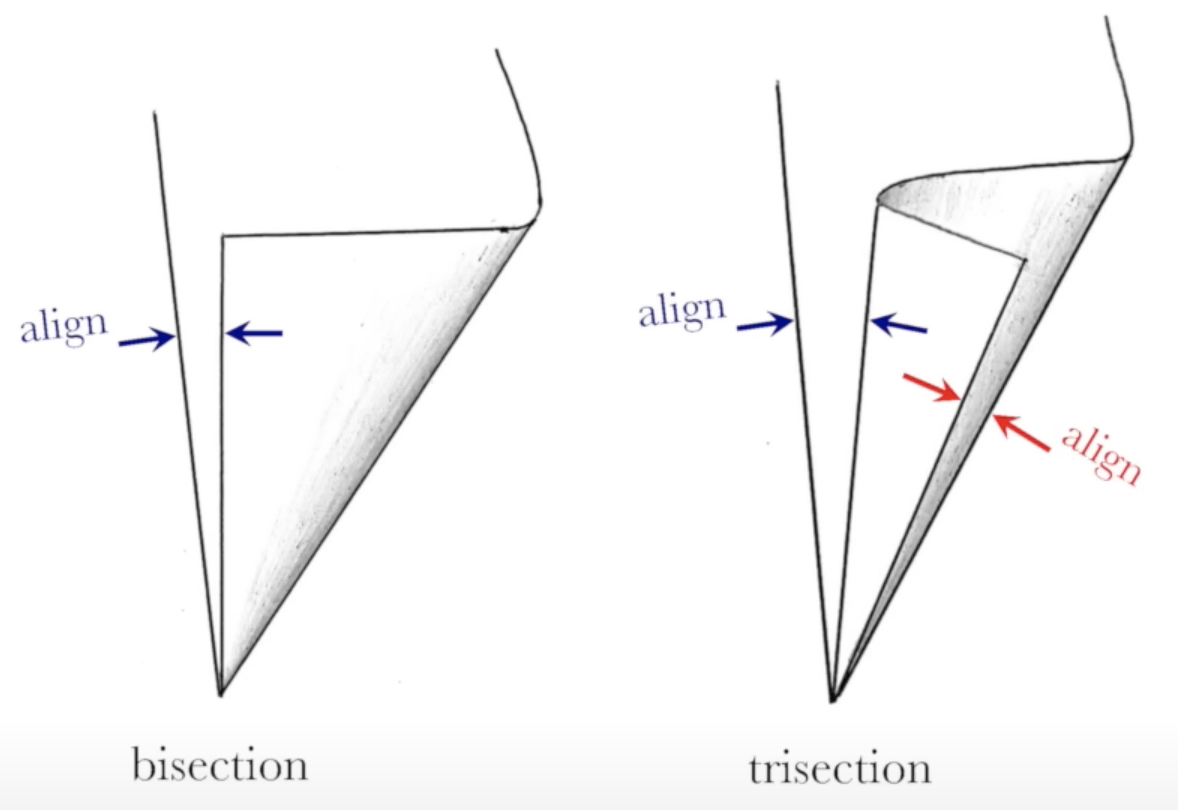

There are several ways to do this: we can use tools like a ruler, or an extra curve, or a string. One particularly illuminating way relies on paper folding, which gives us an entirely different set of axioms. One of these axioms involves 'sliding' the paper to meet a crease (Figure 7), which, while impossible in Euclid's world, allows us to generate cube roots and thus solve arbitrary cubics [2, 3]. This, in turn, allows us to trisect the angle and double the cube.

Figure 7. Trisection using origami. Image from [2].

The point of all of this is to say that the reason that these constructions are 'impossible' is simply a consequence of the choice of our axioms. Euclid's postulates are a good framework for doing geometry, but they are not the only such framework. Algebraically characterizing these geometric axioms allows us to prove their limitations.

References

- Dummit, David S. and Richard M. Foote. "Classical Straightedge and Compass Constructions." Abstract Algebra. 3rd ed. John Wiley and Sons, 2004.

- Tokieda, Tadashi. "A world from a sheet of paper." Oxford Mathematics Public Lectures, Jun. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8p02DtmyQhU.

- Hull, Thomas C. "Solving cubics with creases: the work of Beloch and Lill." The American Mathematical Monthly 118.4 (2011): 307-315.