This 1920 film was adapted into a short story for the Photoplay Magazine and appeared in the June 1920 issue.

|

|

| Their social friends believed that Dan and Madge went South. Instead, they sold most of their possessions and went East--way over east in a part of New York City unknown to their friends. |

IT was after that gay holiday party at the Hunts Club that Madge Hillyer found out for the first time how they really stood in a money way--Dan Hillyer, the boyish but brilliant young inventor whom she had married, and herself.

It had never occurred to her to inquire into Dan's financial status. All the men she knew had money. After a few seasons of judicious flirtations, in which she had been sought by some of the most desirable bachelors of New York, she had met Dan Hillyer and discovered that she loved him. That was enough.

It would have made no difference in her final choice of him if she had known that he was what would have been termed in her set a poor young man. But she would have started out on their little matrimonial venture in a very different way. She would have taken a modest apartment in Brooklyn or in one of the cheaper districts of New York City, for she was a sensible person. She would have worked out an economical household budget system that would have made the money Dan did have last them a long time. Madge was that kind of a girl.

It had been Dan's fault that they had set up in a smart and expensive apartment house overlooking the Park, and had proceeded several months on a season of quite unnecessary extravagance before the subject of dollars arose between them.

Dan had a youthful, stubborn pride, which was one of the things that made him lovable, but this pride, coupled with the unusual delicacy of feeling that besets young people about to be married, had kept them from coming down to brass tacks on the matter of the wherewithal on which they were to live after they were wed. He had indicated that he had realized importantly on a mine windlass patent; but had never told her that the extent of his realizations had been only $15,000--a large enough sum in some circles, but nothing in theirs. Madge had taken it for granted that they had plenty.

Arthur Crewe was at the Hunts Club ball. He had been one of Madge's most persistent suitors--a handsome, serious, somewhat older man of cultivated tastes and the money to indulge them. He was a worshiper of beauty and Madge's fragile loveliness had always appealed to him as a rare flower he would like to own and cherish. Immediately after Madge's marriage he had hied him off for a trip half way across the world-- but the restless longing to talk with her again, to be where she was, to give himself the exquisite pain of seeing her, though married to another, brought him back for the annual club affair at which they had danced each year since she had been old enough to be out and about . He felt--he knew--that he would never love another.

Dan Hillyer, watching his wife dancing with Arthur Crewe, read all the older man's thoughts in the dark brown eyes that bent on her. Dan could see the misery--yet pleasure--that Crewe felt in her nearness. He was seized with a violent jealousy, joined with a sort of vague fear of the money and power that Crewe possessed--which served to make him a little bit irritable after they reached home. A most inopportune time to expose the fact that the household had accumulated bills--a whole teapot full!

"I just stick them in there," Madge laughed as she pulled them out of the silver pot so that she might put Dan in a more cheerful frame of mind with a cup of tea, "and when there isn't room for any more, I pay them. Simple, isn't it?

When Madge returned from the kitchen with fresh water for the kettle, she found her Dan seriously counting up the bills. She stopped in surprise.

"What's the matter?"

"Matter?" answered Dan. "Heavens, Madge, how could we have spent so much money?".

Madge stiffened perceptibly. Dan had always insisted on her buying all the things she wanted. She told him as much.

Dan's eyes fell in embarrassment--then he raised them and looked shamefacedly at his wife.

"When I won you from--from Crewe and the rest" it was agony for him to confess it--"from all the men who had plenty of money--I--I couldn't bear to let you think you had suffered through your choice. I never told you the whole truth about my finances, Madge. It was not a fortune I got from my wine windlass patent. It was only fifteen thousand dollars. I was sure I could sell the new smelter process before that money was gone--but--but I'm not so sure now."

"Oh, Dan, Dan, why didn't you tell me before, my dear?" Madge went over to her husband and put her arms about him. The thought that he had been working on and worrying without her sympathy and help, while she had been practically throwing money away, that he had been discouraged perhaps, and all because he had not known how willing she was, how anxious to be a real inspiration in his life--hurt her more than Dan's weakness in not telling her the truth before.

"But you still have faith in the smelter process, haven't you?" Madge's practical mind, given a chance, reached out to tackle their problems.

It will be very valuable to the copper industry," Dan answered with certainty. "But it takes time to work out the details--more time than I thought."

"Well, we still have a little money left," said Madge. "We'll sell most of our things, and we'll save all we can while you finish your work. Why--it will be fun to be poor, and to help you, Dan. But my dear"--a flood of tenderness for this foolish boy of hers rushed over her and filled her eyes with tears--"my dear, if you had only told me in the beginning. Now Dan, "Madge's cheeks flushed and her voice grew soft, "now we must win out, you and I--because--because--"

Dan Raised Madge's drooping head, and forced her to look at him. There was a tender mother love in her eyes. He clasped her to him.

THEIR social friends believed that Dan and Madge Hillyer packed up and went South the following week. Instead, they sold all but a few possessions and went East--way over East in a part of New York City as unknown to their friends as the heart of Africa--even less.

On the edge of the East Side with its crowded tenements, its seething, dirty streets, its push-cart markets, its jargoning bargainers. Madge found a tiny apartment in a rather new house watched over by a kindly dispositioned janitress, Mrs. Sherman. It was clean, it was comparatively cheap, and its handiness to the curbstone vegetable dealers and the inexpensive stores, where those who were really poor could find things within their means, made it desirable from Madge's new viewpoint. At any rate, the novelty of the experience wooed her into forgetfulness of its sordidness, at first.

And how she economized! How she scrimped and saved! How she planned--while Dan put the finishing touches to the invention on which they had staked everything they possessed and helped her with the housekeeping all he could.

One day, several months after they had entered upon their new existence, a letter arrived at the Hillyer flat addressed to Dan. It came just at the moment when Dan, clad in pajamas and bathrobe, was pressing the one and only business suit that remained.

Madge was out marketing. Returning, she found her husband frisking about like a little boy. He rushed to her, grabbed her in his arms for a resounding smack--but not before she had managed to slip a box she carried behind the bedroom door--then handed her the letter. It was from the secretary of Colonel Elijah Barnard of San Francisco, president of one of the largest smelter plants in the world. She read:

"Dear Mr. Hillyer:

"Colonel Barnard directs me to say that he is much interested in your smelter process and will be pleased to see you at the eastern offices of the Coast Smelting Company at your earliest convenience.

"Dan," Madge exulted, taking his face between her hands, which had become calloused and worn during her months of unaccustomed work, "I am so proud of you, dear."

|

|

| Madge looked up into his white face and blood-shot eyes. "Go!" she said between taut lips. "If you don't I--I think I shall kill you!". |

Dan went back to his pressing, but as he looked down on the worn trousers spread out on the board, he gave a grunt of dismay.

"Oh, Madge," he despaired. "look at these. Like the one-hoss shay, I'm going all at once."

Madge picked up the trousers to examine them more closely, and as she stretched the thin fabric out to see the extent of the worn place, it gave way.

Madge looked at Dan in horror. A sudden burst of anger--anger at circumstances, at Fate--seized Dan. He jerked the trousers from Madge's hands and tore he to pieces, then stamped on them..

"I wore out that suit in their confounded chairs, awaiting my chance, and now"--he snorted, pacing up and down--"now--oh, it's too ghastly! Madge, we're ruined, unless-- a sudden hope springing up in him--"you can do something."

Madge had accomplished so many things these past few months--had produced so many needed things out of thin air, that Dan had acquired an almost childlike belief that her powers were unlimited. And indeed, though Dan did not know it, Madge already had done something to replace the now ruined garment. That afternoon the had gone to the little second-hand shop where Anton, the friendly Jewish tailor, made old clothes look as good as new.

Dan's eyes opened wide in happy surprise when that box slipped surreptitiously behind the bedroom door appeared draped on the end of a broom through the partly opened bedroom door a moment later. The box held a dark gray suit."

"Remember the old suit you scorched with acid?" Madge demanded between kisses, when she had been dragged with the broom handle from behind the door. "I had the tailor rip it apart. Isn't it marvelous?"

"Marvelous," agreed Dan. Then a disquieting thought struck him--even this must have cost money."

"I found that I didn't need lunch, Dan. Two meals a day are more than enough for me--so when you've been gone at noon, I've just saved the money--and in other ways." She said nothing of the clothes she had gone without.

COLONEL BARNARD listened with real interest to what Dan Hillyer told him in the Eastern Offices of the Coast Smelting Company. Beside them was the model of Dan's smelting process improvement. But in the midst of their conversation the Colonel pulled himself up sharply, took out his watch, then rose with outstretched hand.

"It's most interesting, Hillyer," he said. "But I've an important meeting in ten minutes. I'm sorry. I wish I might have a longer talk with you before I leave for the West tomorrow."

His tone was encouraging, friendly. Dan could not bear to let this moment slip without making an effort to bring the Westerner to some sort of bargain. An idea entered his mind--an idea which a few months earlier would have occurred to him, perhaps, as a matter of course. Today it was very daring. This one meal would cost as much as it took them to live a week, or maybe two.

"Can't--can't you have dinner with me tonight,"--Dan gulped--"at--at the St. Croesus?"

Dan paused in scared silence. The Colonel accepted his invitation.

Colonel Barnard seemed to enjoy his dinner immensely--and ate, as Dan afterwards complained to Madge, like a poor relation. But the meal was a miserable one for the young inventor. Through it all he was haunted by the fear that the Colonel would go away without giving a definite promise in regard to his patent--and that would mean the price of the dinner wasted. Then, too, the picture of Madge came to take the cheer out of his heart.

She had been so horrified at first at the money it would take for this one act of propitiating Fate--then, poor child, she had broken down and wept because she could not go to the St. Croesus too. She had laughed through the tears at herself for being a silly baby as she handed over the household emergency fund. Dan understood the heart hunger for a taste of her old life that had swept over her--and he hated the brilliant hotel, its music and its audacious price-list, which had made it impossible for him to bring her along.

The upshot of the dinner was a terrifying bill and an invitation for Dan to come to the Coast to demonstrate his invention to the Colonel's board of directors. Barnard offered to pay Dan's expenses, but he neglected to advance the money.

Madge, starting from the big chair where she had curled up, a shawl about her shoulders, to wait for Dan, found black despair written on every feature of his face on his return.

|

|

| Lack of absolute confidence means the wreck of many a beautiful romance-- |

"But Dan--we still have money in the bank," she said when he had told her the evening's story."

Dan answered firmly: "I know dear, but we're saving that for you. We can't touch that."

"But I'll be all right," Madge insisted. "I'll leave enough and you'll be back long before--before--"she hid her face a moment on his shoulder, "and then we'll be rich. It's your big chance, Dan. We mustn't let it slip."

The next morning Madge Hillyer drew the $300 from the savings bank. As she left the bank, a man, by seeming accident, stepped into the same revolving door compartment as she. When she reached the corner she discovered her handbag was gone. Involuntarily she cried out. A crowd gathered--but the thief had disappeared.

|

|

| --While with perfect understanding, "nothing ill can dwell in such a temple." |

WHAT should she do? She must act somehow without letting Dan know. For some reason her thought went to Crewe--perhaps it was because he, back in his apartment after another unsatisfying trip into strange new countries, was thinking intently on the Madge he had one time loved. He determined to crucify her pride and go to him for help.

Yamadici, Crewe's Japanese servant, admitted Madge into a living room rich with soft woven hangings and vivid with many colors. The fragrance of flowers came to her nostrils, and a plaintive melody, played with Crewe's touch on a piano, crept to her from another room.

Yamadichi disappeared for a moment, then came back to say that his master would see her. Madge trembled as she followed the silent Jap, trembled at the audacity of her coming here, trembled more at the memory of happier days. Of a sudden the stuffy, smelly apartment, the unattractiveness of her luxury-stripped life, repelled her. She became faint.

At the sight of the pale Madge in her shabby garments, Crewe's expectant manner changed o one of frank disappointment. He had expected to see the graceful, vivacious creature of his dreams.

"What can I do for you?" he said stiffly, after an embarrassing pause.

"Arthur"--she was the practical, self-controlled new Madge again. "I want $300--as a loan for a month." She shrank from the coldness of Arthur's look, but she forced herself to tell him of their struggles--hers and Dan's.

"We'll pay you interest--eight or nine per cent if you want it," she finished.

"Thanks." Crewe's tone was frigid. "I'm not a loan shark. Why not go to one of them?"

Madge smiled bitterly.

"I thought of that--but we have no security to offer."

"Then what security could you offer me?"

Madge looked at the man who had one time loved her straight in the eye, then gathering all the scorn she possessed in the voice, she said, "Myself."

Arthur Crewe winced perceptibly. For an instant the flame of old desired leaped up in his eyes, and died down again, to a look of hurt misery.

"Madge, you might have spared me this!" he cried. "You have wrecked my dreams. The very sight of you--worn, haggard in your slavery to that man--shattered all that was left to me, my memories, and now--this!"

He came closer, his face growing white. "Why should I waste money on a woman whose looks and vivacity are gone--who is frankly selling herself--"

As the significance of his words sank into her dazed consciousness, at the knowledge that any man who knew her as well as had Arthur Crewe could so have misunderstood her, Madge drew herself up to her full height.

"You beast! You dared imagine that I meant--"

"What did you man?" ask Crewe in honest bewilderment.

I meant myself--myself with all the power for working, and saving and starving. I'll work my hands to the bone until the debt is paid."

"Madge! Forgive me. I didn't know--" Crewe was humbly apologetic.

"There are some things a woman never forgives." Madge said quietly. "Let me tell you that no matter what you decide to do, I shall never forget the abominable insult you have offered me today. I tell you that, so we may be above board. If I had not been desperate, you may know that I would never have come in the first place.

DAN HILLYER got safely away to San Francisco that afternoon, without guessing what the cost had been to his wife.

"God help us both," Madge whispered to herself as the train pulled out of the depot. Then she started wearily back to the East Side and the shabby apartment.

ARTHUR CREWE spent the most unhappy hours of his life the night after Madge's call. Now that the first shock of seeing her had softened, he was tormented with the knowledge of her poverty. He was tortured with the thought that he had misunderstood her, that he had insulted her. And he knew that thought the old fairy Madge had disappeared, it was the soul of her that was beautiful--that he loved.

In the morning he left the house to see if walking would relieve his mental distress, and almost without knowing it, he found himself at the address Madge had given him as hers.

With some difficulty he ferreted out the door to the Hillyer apartment and rapped. From within came the sound of some one walking, then there was a dull thud and all was very still. Crewe rapped again and again, each time louder, until the janitress heard him and came running.

When Mrs. Sherman had opened the door with her keys, they found Madge lying still and white on the floor.

Arthur Crewe picked the unconscious form up in his arms and laid her gently on the bed, then rushed out to call an ambulance.

"Poor dear, poor dear," sighed Mrs. Sherman when he was back again. Many's the time I told her she should be more careful of herself--not work so hard."

"What are these?" inquired Crewe, noting a pile of envelopes on the table. They were addressed to "Daniel Hillyer, Care Coast Smelting Company, City Bank Building, San Francisco, Calif."

"She wrote a letter for each day," answered the woman, wiping he eyes. "It was the last thing she had the strength to do. "I'm to send one to him on every morning's mail--so he won't worry."

As the ambulance bearing Madge Hillyer to her hour of trial clanged out of sight, a telegraph messenger arrived at the apartment door. Arthur Crewe was just leaving. He opened the envelope, addressed to Hillyer.

"If not started," the telegram read, "postpone trip. Must delay action on patent until vice president's return from South America next spring. Am writing,--ELIJAH P. BARNARD."

Crewe folded the envelope with a grim smile on his face. What fateful irony this was.

|

|

| When a husband pays, as interest on the bonds of matrimony, pretty little attentions to his wife-- |

ARTHUR CREWE hovered in the background the next few days while Dan Hillyer's wan young wife hung between life and death. He saw to it she had a private room and paid for extra nurses. But she did not improve. She took no interest in anything--not even her baby.

"She hasn't the will to live. Her vitality's been sapped. The fight has gone out of her." the specialist said.

To Crewe as he heard this there came an idea of forcing the young mother to save her own life. But when told of the plan, the doctor stared at Crewe as if he were mad.

"Why, man, she'd hate the very ground you walk on if she should live.

But Crewe was firm. "She does anyhow," he mused. Then aloud: "It will make her fight."

A moment later the doctor bent over Madge's drawn face and spoke her name very harshly. When the dark lids stirred, he said slowly, but sternly: "Mrs. Hillyer. Listen to me. Your husband has failed. Do you hear me? They won't buy his patent. and Mr. Crewe wants to know when he is going to get his money."

|

||

| --The "K.P. of the home ceases to be a drudgery and the bluebird of happiness flies in. |

Madge's eyes opened wider.

"The money you borrowed," continued the doctor. "Mr. Crewe wants to know if you are going to cheat him out of it."

"Tell--him," the doctor had to bend low to catch the faint words "--I'll--pay." Madge's brown eyes closed.

"By Jove, Crewe," said the specialist, coming into the corridor, "you're a better doctor than I am."

WHEN Madge Hillyer returned home with the Baby Dan, three letters--registered--awaited her. As she opened them, a perfect shower of money orders fell to the floor. Mrs. Sherman, who had brought the letters, picked up the pieces of paper. There were ten of them for one hundred dollars each. A fortune!

"I followed Barnard to Butte and back again--and was as welcome as the hives," read one of Dan's letters. "He said I was just wasting my time and his. Then overnight, he changed--Heaven only knows why. The next day her received me with open arms. Bonus of $15,000 and a royalty guaranteed not to drop below $10,000 a year for the next fifteen years."

"We're rich, Danny boy," cried Madge, holding he baby tight to her heart. "We're rich."

Before Dan's return she had deposited the money orders and mailed Crewe a check for the $300, wishing to wash her hands of this loan that had haunter her out of the valley of the shadow. She wanted to put Arthur Crewe from her life forever.

JACK LONDON tells of a man who, escaping starvation in the frozen North, after his rescue used to steal crusts from the dinner table and hide them away in fear of starvation again. And so, in a different way, it was with Madge Hillyer.

Her suffering in so critical a time had left its mark deep upon her. The thought of a return to poverty made her shudder in terror. She could not bear to spend or enjoy the money that had come to them as a result of her toil and sacrifice. Dan's happy recklessnesses--occasional flowers, a beautiful ring, toys for t Little Dan--filled her with dread instead of pleasure.

"Dan, we must save," she would repeat. "The horror of what we have gone through haunts me. It must not return. It would kill me to go through it again!"

"I mean to save within reason," Dan would reply, irritated by her insistence. "But we don't have to be silly about it."

And so the question of dollars--always dollars--even now came to loom between them and threaten to destroy their happiness.

It would seem that dinner at the St. Croesus, the opera, supper at a gay cabaret--these should have aroused Madge's late love of gayety and luxury. Dan insisted on taking her out to these places one evening, when he felt that her obsession for saving was driving him to distraction. Her spirits rose when she donned her evening gown, which had lain idly in her closet for so long. The color came back to her cheeks and her eyes sparkled. Dan's old time impetuosity returned and he caught himself kissing her hand over the table. But before the evening was over they were jangling again.

"You didn't hesitate to spend money on yourself when you needed it at the hospital," Dan remarked. "Not that I regret it--I'm glad you did."

"It was all free--furnished by the city," answered Madge heatedly. "I didn't spend a cent."

"Then who did spend it?" asked Dan. "You can't tell me the city gave you a private room and two nurses for nothing."

As they left the cafe, angrily, they passed close to a table where Arthur Crewe was seated. He had been watching them. He started to rise, but Madge only nodded at him coldly and passed on.

The unnatural relation which had arisen between Madge and Dan Hillyer over money led them both to do despicable things, which neither would have done under ordinary circumstances. Driven by a sort of inexplicable doubting and jealousy, Dan went to the hospital where Madge had been ill and demanded to know about her bill. It had been paid, but when Dan asked by whom, "Ask your wife," was the superintendent's calm answer.

He hurried home. Madge was out and being alone, he sat down to work out plans for a laboratory in which to work out further experiments. A question of the price of a piece of apparatus bought by Madge came up in his mind, and he turned for her check book. As he glanced through the stubs, his eyes suddenly became riveted on a certain one. His hand began to tremble, and he let the book drop from his fingers.

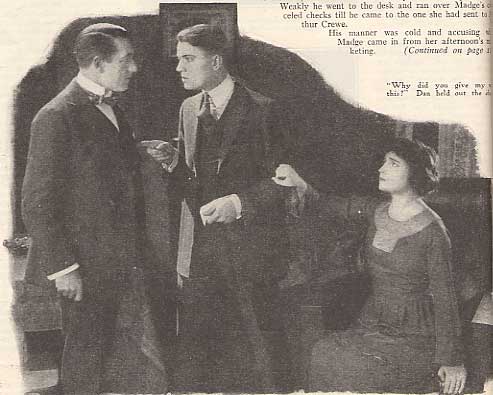

Weakly he went to the desk and ran over Madge's cancelled checks till he came to the one she had sent to Arthur Crewe.

His manner was cold and accusing when Madge came in from her afternoon's marketing.

"I learned at the hospital that someone paid your bill, Madge. You told me that no one did it. That was not true."

Madge looked at Dan in silence.

"And then I found this," Dan continued, producing the cancelled check.

"I paid nothing at the hospital. Neither did Mr. Crewe. That check was for--another matter." For a moment she was tempted to tell him the truth, but decided not.

"Some one paid, I tell you! And why not Crewe? He was your old sweetheart," Dan continued, beside himself with jealousy and rage. "But how did you repay the rest? This would not have paid your bills for a week. Men like Crewe don't pay bills for a woman they love without a reason--and wives don't lie without--"

Madge looked into the white face and blood-shot eyes of her husband with evident loathing.

"Go!" she said between taut lips. "If you don't, I--I think I shall kill you!"

Dan took his hat, and went out, leaving her alone.

ARTHUR CREWE, arriving at the Hillyer door a few minutes later, came in just in time to interrupt Madge in the act of throwing all her clothes and those of the baby into bags and trunks. Dan's distrust of her had killed all the love she had for him. She was gong to leave him--to find a place where she might have peace.

"Why did you come?" Madge asked angrily of Crewe.

"Because I cannot bear to see you unhappy in spite of my sacrifices," he answered quietly. "It was to save your life that I demanded the $300, Madge. I made you despise me, so that you would fight for your life. Otherwise you never would have pulled through. I never would have told you--in my heart I had given you up forever---but Madge, Madge, I saw how unhappy you were last night. You must come with me, dear. You could not earn a living. I want you to go to my sister till you can get a divorce. Then I want you to marry me.

Madge's expression changed from loathing to wonder as Crewe talked, then her eyes filled with tears.

"I don't ask your love. I won't force mine on you," Crewe added gently. "I just ask for the right to make you happy."

Dan, entering the hall door with his pass key, heard the last words.

"Your wife is leaving you," Crewe said, turning to Dan. "I have asked her to divorce you and marry me."

Dan turned to Madge. His walk in the air had calmed him.

"Yes," she said hysterically, "I am going. I wanted to get away before you came back."

Dan went to the desk and got his revolver, then broke it and took out the cartridges and handed the gun to Crewe.

"My temper is none to sweet at times," he said. "There will be no scene unless you make it, Mr. Crewe. Now as I understand it, you wish to marry Mrs. Hillyer to atone--"

"I wish to marry her beacuse I love her. In her case there can be no question of atonement, and if you were not an utter fool you'd know it."

"But why did my wife give you this?" Dan held out the check.

"It was the money she borrowed to send you West. The money she drew from the bank was stolen on the way home."

"Then who paid the hospital expenses?" Dan demanded.

"I did," answered Crewe. It was Madge's turn for bewilderment now.

"That was a matter of which your wife was entirely ignorant."

There was silence in the little room then Dan Hillyer spoke.

"Crewe, if Madge decides to marry you, she'll get a man, a real man clear down to the ground."

It was several moments before Madge raised her voice.

"You will understand, Dan," she said, "that when I leave you, I shall go wholly out of your life. If the baby is to be with me, you can never see him."

"He belongs to you. You would not be happy without him," Dan replied. "I have been selfish enough. I have nothing more to say."

Madge looked for a moment at her husband. The thought that Dan was willing to make this sacrifice for her, that he was willing to give up his child as well as her for her happiness' sake, proved that he loved her--and her old love for him came tumbling over the barriers.

"Arthur," she said, turning to Crewe, "you have sacrificed much for me, but could you do--what he has done?"

Arthur Crewe was too honest to pretend. He turned away and went out silently as Madge found her old happy place in Dan's arms.

|

||

| "Why did you give my wife this?" Dan held out the check. |

"I don't care if you spend everything you have," she whispered in his ear.

"Spend? Why, I'm a miser from now on. I'll choke the Indian on every penny I get," answered Dan Hillyer. And he kissed her.

BUT neither Madge nor Dan ever knew that the reason for Colonel Barnard's change of mind over night in regard to the smelter process patent was an order that came from certain directors of he company in New York, who demanded that the deal be closed--and that the reason back of the directors was a rich young man named Arthur Crewe.

Dollars and the Woman

NARRATED by permission from the Vitagraph production, adapted from book by the same name by Albert Payson Terhune, and directed by George Terwilliger with the following cast:

| Madge Hillyer | Alice Joyce |

| Dan Hillyer | Robert Gordon |

| Arthur Crewe | Crauford Kent |

| Mrs. Sherman | Jessie Stevens |

Special contents © 2003, by Greta de Groat, at gdegroat@stanford.edu . All Rights Reserved