|

||||||||||||||

The results of expressing a constitutive form of a prominent synaptic kinase in transgenic mice suggest how there can be a sliding threshold for synapse modification, an important element in some learning theories.

Experimental neuroscientists who work on synaptic plasticity

usually spend their time down at the molecular level investigating

basic mechanisms, whereas theoreticians who inhabit the abstract

world of neural network models hardly ever consider biochemical

events. So it is rare, but extremely gratifying, when an advance

on one front actually clarifies the picture on another. A

case in point is a set of studies from Mayford, Kandel and

colleagues, published recently in Cell

[1]

[2]

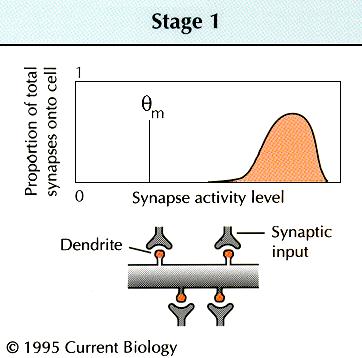

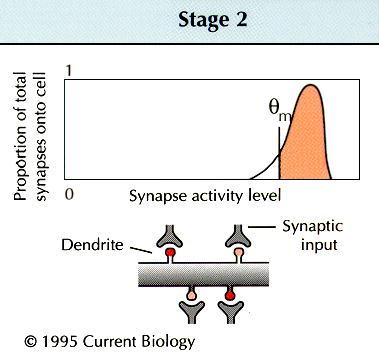

. These papers describe the functional and behavioral effects

of expressing in transgenic mice a constitutively active,

mutant form of a key synaptic enzyme, the CaMKII is known to be important for stable changes in synaptic strength — both hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) [5] [6] [7] [8] . Mayford et al. [1] introduced into mice a transgene encoding an altered form of CaMKII — CaMKII(T286D), in which threonine 286 is replaced by aspartic acid to mimic the effect of autophosphorylation; this change makes the enzyme constitutively active even in the absence of calcium or calmodulin [3] [4] . When the basic synaptic physiology of these transgenic lines was tested, the resting or basal synaptic strength appeared normal, and synaptic plasticity appeared not to have been directly induced. Strikingly, however, a fascinating change was seen to have occurred in the rules governing plasticity. Synaptic stimulation at a frequency that would have induced a slight LTP in wild-type mice instead induced robust LTD in the mutants. Furthermore, the amount of depression induced correlated well with the level of calcium-independent CaMKII activity achieved. These results strongly indicate that the genetic manipulation specifically altered the decision-making mechanisms for plasticity — exemplifying a phenomenon that has long interested neural theorists [9] , and that has recently been termed 'metaplasticity' (W.C. Abraham, personal communication, and [10] ). A simple example of metaplasticity is shown in

Fig. 1

. Consider a synaptic pathway that gives a fixed response

(shown as an excitatory postsynaptic potential in

Fig. 1a

) under basal conditions, and that undergoes LTP when subjected

to an inducing stimulus pattern (*). Now suppose that, after

a special intervention (†), the same stimulus pattern (*)

instead causes LTD. The changeover from one form of synaptic

strength change to another is a kind of plasticity of plasticity, or

'metaplasticity' (W.C. Abraham, personal communication, and

[10]

). Notice that the metaplastic change might be tricky to

detect — the obvious functional properties of the neurons need

not change at all. Instead of seeing a change in synaptic strength

itself, the experimenter might only see a change in the rules

used by the neurons to change synaptic strength. For example,

hippocampal or cortical synapses appear to implement a well-defined

function for altering their strength in response to different

inducing frequencies: lower stimulation frequencies induce

LTD, and higher frequencies produce LTP

[11]

. Metaplasticity might involve a change in the threshold

frequency, |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Can metaplasticity actually occur in the brain? In recent years, a number of groups have reported synaptic phenomena that can clearly be classified as metaplasticity [12] [13] [14] , and some have provided initial clues as to its mechanism. Huang et al. [12] showed that synaptic activity which does not itself cause a stable synaptic strength change can prevent later LTP, by a mechanism requiring calcium influx through N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors. In their hands, the metaplasticity was synapse-specific and lasted less than an hour. Similarly, O'Dell and Kandel [13] observed a transient prevention of later LTP by prior non-plasticity-inducing synaptic activity, and went on to show that this metaplasticity required activation of protein phosphatases. Other studies have suggested the involvement of a protein kinase C in this kind of metaplasticity [15] [16] . How might metaplasticity be stored in a neuron? Covalent

modification of proteins is a plausible biochemical mechanism.

One of the first possibilities to be considered was phosphorylation

of the NMDA receptor itself

[17]

. If this modification were to reduce calcium entry through

activated NMDA receptors, synaptic stimuli that normally induce

LTP might fail to do so, as in the experiments of Huang

et al.

[12]

and O'Dell and Kandel

[13]

. On the other hand, Mayford et al.

[1]

considered that the storage of metaplasticity might involve

an intracellular signalling enzyme downstream of the NMDA

receptor

[17]

— the First, consistent with previous work on young rats

[18]

, Mayford et al.

[1]

showed that, in wild-type mice, basal calcium-independent

CaMKII activity was higher in young animals than in adults,

in parallel with the prominence of LTD in young animals. They

also found that the quantitative relationship between enzymatic

activity and the propensity for LTD was the same for transgenic

as for wild-type mice; no more LTD was observed in young transgenic

animals than in either young wild-type or adult transgenic

animals. Thus, youth and Next, experiments were conducted to test the effects of

combining high-frequency stimulation and expression of The overall conclusion is that the effects on LTD of In a companion paper, Bach, Mayford and colleagues [2] report the results of testing the transgenic mice for behavioral abnormalities in two hippocampus-dependent learning tasks. Strikingly, the transgenic mice showed deficits in spatial memory, as tested in a Barnes maze. Their contextual fear conditioning, however, was normal, indicating that some types of hippocampus-dependent memory are intact. These results are consistent with the view that metaplasticity is important in spatial memory, but also leave open other possibilities involving developmental effects of the transgene. As intriguing as all this work is, we still do not know

how the plasticity threshold is shifted (see

box

). CaMKII has at least two possible actions, as a multifunctional

kinase, and, given its high concentration in neurons, as a

regulatable calmodulin sink. This latter property becomes prominent

upon autophosphorylation, which increases the kinase's affinity

for calmodulin 400-fold

[22]

. Perhaps it is the kinase activity of CaMKII that is involved

in the weakening of NMDA receptor responses following a bout

of low-frequency stimulation

[23]

. The resulting reduction of calcium influx would be expected

to tip the balance away from LTP towards LTD at any frequency.

It is unclear whether such changes in NMDA receptor properties

can be induced, directly or indirectly, by CaMKII

[24]

. However, mice lacking In another possibility that Mayford et al. [1] considered, the calmodulin-buffering properties of autophosphorylated CaMKII [22] come into play. Presuming that CaMKII(T286D) traps calmodulin as efficiently as the autophosphorylated kinase, it might sequester synaptically-generated calcium– calmodulin, and thereby reduce the effects of calcium– calmodulin on other enzymes. This idea could be tested by looking at metaplasticity in transgenic mice expressing the calcium– calmodulin-binding peptide of CaMKII in the absence of any of its other regulatory or catalytic domains. Mayford et al.

[1]

found that expression of constitutively active CaMKII in

transgenic mice caused neither direct enhancement of synaptic

strength nor occlusion of LTP. This is contrary to recent work

from Pettit et al.

[8]

, who introduced the gene for a truncated, constitutively

active form of A more interesting possibility is that the discrepancy

between the results of Mayford et al.

[1]

and those of Pettit et al.

[8]

arises from differences between the active forms of CaMKII

that were introduced. The T286D mutant that Mayford et

al . used

[1]

would be able to form heteromultimers with wild-type Returning to the issue of metaplasticity, the selective alteration to the threshold between net depression and potentiation [1] [2] may be only one of a number of forms of metaplasticity. Based on a reading of the literature, at least two types of metaplasticity might eventually be differentiated on the basis of their temporal properties, degree of synapse specificity and, perhaps, biochemical mechanism. In one type, changes in LTD/LTP induction would be synapse-specific, induced immediately and last approximately an hour [12] [13] . These changes might be implemented by modification of the NMDA receptor itself, or of some other post-synaptic protein, but are unlikely to involve changes in gene expression. Surprisingly, whether CaMKII has a role in such a modification has not yet been tested. Another type of metaplasticity, of the sort envisioned

by Bienenstock et al.

[9]

, would not be strictly synapse-specific, in contrast to

the first type. According to their theory, the threshold At this stage it is unclear whether the metaplasticity

studied by Mayford et al.

[1]

belongs squarely in either of these two categories. In

principle, expression of the CaMKII(T286D) transgene could

mimic a global, nucleus-dependent change consistent with the

latter type of metaplasticity. New gene expression is known

to be required for the consolidation of long-term memory

[26]

, as well as for the stabilization of long-lasting synaptic

plasticity

[27]

; interestingly, expression of the endogenous gene for

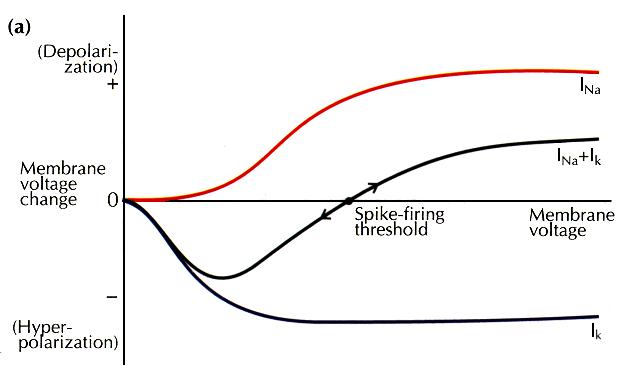

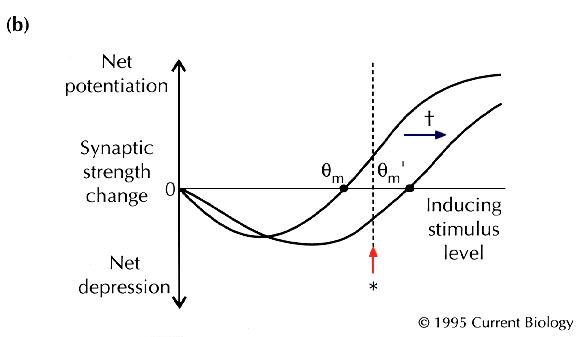

How can a sharp threshold be achieved? Real biochemical processes do not show an absolute threshold, but are gradually augmented by increasing input. However,two processes that are largely overlapping but of opposite sign can combine together to produce a net effect that changes sign at a crossover point. This point will represent a threshold — an unstable point — if small perturbations on either side lead to runaway deviations from that point. Example of this are the ignition point of a bomb or the threshold for nerve excitation. In the case of excitable tissues, the overlapping processes are an inward current Na + channels and an outward current carried by Na + channels and an outward current carried by K + channels. Activation of these channels is a graded function of membrane depolarization but, in combination, they can produce a sharp threshold (a). In the case of plasticity control, the overlapping processes correspond to the forces underlying potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD) of synaptic strength. The activation of both these processes is also a graded function of synaptic stimulation strength and, again, in combination a threshold is produced (b). The diagrams are intended to convey system dynamics, and correspond to phase-plane diagrams in which the x axis represents the state of the system, and the y axis represents the derivative of the state. The idea of a sliding threshold is not limited to metaplasticity — that British physiologist A.V. Hill proposed just this concept as a way of accounting for accommodation of spike firing in nerves subjected to slowly rising stimuli. Depolarization was proposed slowly to increase the threshold potential, such that weakly rising stimuli could produce strong depolarization, yet fail to elicit spike firing. What mechanisms could allow a threshold to slide? It may

be helpful to consider how the threshold for spike production

is displaced. In a mechanism uncovered by Hodgkin and Huxley,

the threshold for spike firing is modified by inactivation

of Na+ channels or activation of K+ channels.

These processes are particularly interesting, as they may

persist without a net change in membrane potential. This offers

a possible analogy with modifications of the threshold for

synaptic plasticity ( |

|

|

|||

isoform of calcium– calmodulin– dependent kinase II (CaMKII)

isoform of calcium– calmodulin– dependent kinase II (CaMKII)

m, that separates net LTD from net

LTP (

m, that separates net LTD from net

LTP (

subunits, and would find its normal cellular location.

But the molecule introduced by vaccinia infection was truncated

at residue 290, and would therefore be unable to form heteromultimers

or to soak up calcium– calmodulin. For these reasons, the

use of truncated forms of the enzyme might emphasize different

aspects of CaMKII function.

subunits, and would find its normal cellular location.

But the molecule introduced by vaccinia infection was truncated

at residue 290, and would therefore be unable to form heteromultimers

or to soak up calcium– calmodulin. For these reasons, the

use of truncated forms of the enzyme might emphasize different

aspects of CaMKII function.