Beginning Alone

by Mary Tappan Wright

last section

| Contents |

Next section

last section

| Contents |

Next section

|

IT was almost evening, and the little things had talked in whispers all day, sitting in a corner of the nursery huddled together. An unknown presence brooded over the house. They heard Nellie’s terrible cry; coming after a whole week of hushed voices and muffled footfalls they knew that it meant something. They instinctively felt what was happening and looked at each other in horror, but they would not believe it.

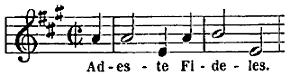

Walter found that “keeping his eye on the children” was a more difficult matter than he had imagined. He had meant in all sincerity what he had promised Nellie to that effect when she went away, but he had not counted upon the intoxicating influence that a sudden accession to power would have upon Elizabeth. As soon as Nellie was gone the little girl was practically her own mistress. She ordered her doings according to her own will, went and came as she pleased, wore her favorite dresses, and stayed up as late at night as seemed to her fitting and convenient. In short, she realized a long-dreamed-of state of freedom. Great was her surprise to find how little pleasure it afforded, for Elizabeth had a most inconsiderate mentor who gave her no peace, but constantly whispered at each wrong turning, “What would mamma have thought?” An uneasy conscience will soon upset the strongest nerves; to this a hasty temper and provoking ways soon testified. Reginald seemed especially to irritate his little sister, and when they were not off on some expedition of peculiar mischief, the house resounded with constant quarrels. Mr. Wharton shut his study door and tried to think he did not hear; and poor Walter, busy every minute with his examinations, found his methodically arranged hours sadly interfered with, and grumbled freely to Mr. Cornelius about the daily increasing amount of “baby-tending” imposed upon him. “Elizabeth is brim full of wilfulness,” he said. “She keeps Reginald in a constant stew. He said this morning that he was going away and never coming back.” Mr. Cornelius laughed. The possibility of a mite like Reginald taking life into his own hands had something rather comical in it. He felt secure, however, in the conviction that the little fellow’s childish timidity would prevent his wandering much further than the gates of the college park. But as the days went by Reginald’s threat was frequently repeated. To be sure, he said he was going to Heaven, and his state of temper at such times made the chance of his getting there seem not very likely. But Walter had an unaccountable conviction that sooner or later he would make some strange experiment. Therefore, when one day at dinner-time the child was nowhere to be found, Walter was not even surprised. “Where is your brother?” he said, pouncing on Elizabeth with the question of Cain. “I am sure I don’t know,” answered Elizabeth, suddenly much occupied with her soup. “But he said he was going to Heaven. He started before papa went to Littleton.” “That was before ten o’clock,” said Walter, impatiently. “What were you doing to him?” “Not a single thing. He said he knew how to get to Heaven, and I said he didn’t. And he told me he was going there to-day, and I said he couldn’t. Then he said he would start right away, and I told him he’d better hurry and do it, or he wouldn’t get there in time for dinner. Then he flew into a rage and went off up the path, and I haven’t seen him since.” “Why did you let him go? You know we never allow him to go off alone.” “Oh, well,” said Elizabeth, deliberately, “I thought he would turn back before he got to the gate. He knows it is too far over there.” “Over where? O Elizabeth, don’t be so slow!” “Why, the hill over there where the two tall pine-trees grow,” she said, mentioning a place some two or three miles distant. “You know he always says that Heaven comes down and meets the earth there, and he thinks he is going to get in.” “How long has he been gone?” “Oh, I don’t know! I told you he started before papa. I wish you’d let me alone, Walter; I can’t eat my dinner.” But in spite of this show of peevishness, Elizabeth was at heart anxious and miserable, and had been so for several hours without the courage to confess her fears. Mr. Wharton would not return until seven o’clock in the evening, and as Reginald had been gone three or four hours, Walter felt that the responsibility of an immediate search devolved upon him; so after a hurried meal and some further questioning of Elizabeth, he started out. It was a sultry June day, and Walter was in a mood by no means amiable as he plodded on through the dust. He had not gone very far when he met a farmer driving in from the country. He asked the man anxiously if he had seen a little boy of Reginald’s description. “Oh, that little chap!” said the farmer, smiling. “I gave him a lift on his way home this morning.” “His way home?” “He said he was going to his mother. Anything wrong? He did seem a mighty small boy to go out alone, but when I’d drove with him ’longside o’ me for half a mile or so, I thought I’d never seen his beat for sense.” The man laughed. “How far did you take him?” “Oh, I let him out at the top of the hill, near old Pete Tucker’s! He’s all right! He said the place he was goin’ to was just back of them two trees—that’s Tucker’s. You’ll find him when you get there. He is the beat’nest little chap!” The fanner drove on, smiling over the memory of his morning’s talk. There were two ways to “Tucker’s,” and of these Walter had taken the longer. He knew the place—a little story-and-a-half cottage on the top of a ridge of hills almost directly opposite Dulwich. It was shut in by a tall hedge of mock orange, and stood back about thirty feet from the road. Two great pine-trees, not a common thing in that part of the country, towered up on each side of the entrance, and formed a landmark for miles about. As Walter drew near, hot and dusty, he heard the sound of cheerful voices on the other aide of the hedge, but saw nothing until he reached the little iron gate, which, swung between two stone posts at the foot of the trees, opened on a path of irregularly shaped flag-stones which led up to the front door. There sat Reginald on the north step, conversing affably with an old lady and gentleman, who, sitting on either side of him in large chairs with broad arms, rocked incessantly. The old gentleman was in his shirt-sleeves, and the old lady wore the feminine equivalent of the same—a black petticoat, and a thin white jacket ending in a full frill at the bottom, that divided neatly in two her capacious figure. “Well, here’s Walter, I guess!” said old Mr. Tucker, as Walter came up the flagged walk toward the little group. “O Walter, don’t take me home!” Reginald exclaimed. “I’m having such a lovely, lovely time, and I’m going to milk the cow pretty soon with St. Peter!” Walter looked puzzled, but Mrs. Tucker moved slowly down the step, laughing as she came. “Why, Walter, how you’ve grown!” she cried. “I haven’t seen you since last fall, a year ago. Come up and stay. Dillingham is going over this evening to buy some groceries, and he’s promised to take this little man back in the wagon. Has your father been frightened about him?” Walter signified that his father would not be at home before seven or eight o’clock in the evening, and that all the anxiety had been his own. “Just come up,” Mrs. Tucker insisted, hospitably, “and stay to tea. We’re havin’ it early, because Dillingham’s going to be ready at six, and it takes some time to step down there.” Dillingham was her son-in-law, a farmer who lived about half a mile further on. “You never knew before how near you were to Heaven, did you?” inquired Mr. Tucker, winking at Walter over Reginald’s head. “Now, pa, you just keep still about that, and go to your milkin’,” said Mrs. Tucker. “It’s most five now. Isn’t he the dearest little thing!” she added, looking admiringly after Reginald, as he trotted off by the side of the old man. “He came about half-past twelve and rang the bell. Tucker and me was at dinner, and I told him he better step to the door, as I wasn’t fit, but I just rose up behind him to see who it was, an’ heard a little voice say: ‘Is this Heaven?’ “‘Yes,’ says Tucker. ‘I’m St. Peter, and this’—turnin’ to me—‘is the angel Gabriel.’ “The poor little dear looked up at me, when I came forward, and his sweet little mouth turned down at the corners too pitiful. He tried to steady his under lip while he said, ‘It’s such a dis’pointment!’ I just went down on my knees beside him, fat as I am, and tried to comfort him. “‘Never mind, darling,’ says I, ‘and don’t pay any attention to him. I’m no more of an angel than he is a saint’—and that ain’t much, goodness knows—‘I’m just your old, fat Gran’ma Tucker!’ “He hid his little head right in my neck, and I could feel his tears scalding hot—the dear, dear little pet!”' Mrs. Tucker wiped her eyes and fanned herself with energy. “Since then he’s called me just ‘Mrs. Tucker;’ but the ‘Saint,’ for some reason, stuck in his mind; and Peter, he’s been promoted! Of course we knew who he was the moment he told his name; so we brought him in and gave him his dinner, and from that minute he’s been as jolly as could be. He crept in and out of the hole in the door for the cat, and played with the churn and coaxed my old gentleman around as if he’d been his own grandchild; as for Tucker, why he’s just bewitched! He hasn’t left that child five minutes since he came. And there’s Abraham Lincoln now, lettin’ himself be hauled around in a way I never expected to see!” She nodded her head, as she spoke, toward the orchard, from which Reginald was approaching, holding an immense yellow cat in his arms. The creature was too large and heavy for the child to lift entirely from the ground, but he allowed himself to he dragged along without resistance, his hind legs, between Reginald’s sturdy brown ones, making a feeble attempt at a walk. “This is Abraham Lincoln,” panted Reginald, coming up to Walter. “Isn’t he big?” “He looks like a small tiger,” said Walter, smoothing the cat’s yellow head. “And acts like one, too!” said Mrs. Tucker. “Take care! He hates strangers.” The cat was arching his back and swelling out his tail. “He likes me,” said Reginald. “Come, Abraham!” Getting astride of him, the child again clasped Abraham’s substantial body and marched him off. The tea-time came, and after it Mrs. Tucker bade Reginald good-by with manifest regret. “You little dear!” she said. “You must come again soon. I hate to see you go.” “I’m coming next week,” said Reginald. “If we only went to Dulwich to church,” said Mrs. Tucker with a wistful sort of a sigh, “we could keep him until next week.” “The old lady misses her church,” said Mr. Tucker, suppressing an echo of his wife’s sigh as they left the gate. “I believe you go to Zion now,” said Walter. “It is a Methodist church, isn’t it?” “Yes, it is!” answered Mr. Tucker, defiantly. “I couldn’t stand the ritualism over yonder any longer. I might hev stood the white gownd, I might hev—I don’t say as I should—if it hadn’t been for the chimes. I couldn’t stummick them chimes. Faugh! They make me sick every time I hear ’em!” “Some people like them,” said Walter. “They do,” said Mr. Tucker, solemnly. “They do, and I am sorry to say it. It is about the only thing I have agin my old lady; for on matters of taste we generally agree. But she saunters down to the gate every Sunday morning, when that young Francis is playin’ ’em, and there she’ll sit on the stone seat acrost the road, and look over the valley at Dulwich as if it contained her heavenly home. “It is re-markable how, when we had to start at eight o’clock to drive over to Dulwich to church, she was never late, and now she can’t get ready in time for Zion, down here at the cross-roads, by half-past ten—re-markable! And her health on Sunday’s never been the same.” He smiled openly at Walter over Reginald’s head, as if the “old lady’s” contumacy was not, after all, without its pleasing features. “I am surprised that you can hear them over here,” said Walter. “I shouldn’t think you could unless the wind happened to be in the right direction.” “You can’t unless you try,” said Mr. Tucker, “and I’m thankful for that—the wind don’t blow in the wrong direction more than once a week. But when it does—yang, yang, yang, yang, yang, yang, yang, yang,—fa-a-ugh! it always makes me sick.” Mr. Tucker imitated the chimes with great dramatic effect, and Reginald watched him, reproducing all his motions in unconscious sympathy. “Do it again!” he cried. “It is just like them. Do it again.” The two stood still in the road while the whole sixteen strokes that rang the full hours were rehearsed with a mawkish expression, every shade of which was treasured by Reginald for future displays. They soon reached the Dillinghams’ gate, where the farmer was waiting for them already in the wagon; and it was during the drive back to Dulwich that Walter composed the telegram which started Nellie on her homeward way the following afternoon. Confident that she would have arrived, Walter took Reginald and Elizabeth down to the station to meet her. The poor boy, in doing so, had some forlorn idea of making the home-coming somewhat less desolate, and the little ones looked up eagerly as Nellie stepped off the car. “Can those be the children?” she asked herself. Was this thin, untidy, long-legged creature, with straggling elf-locks and wrinkled stockings, her dainty, picturesque little sister? And this grimy-handed child, with buttonless boots and jacket covered with spots—it could not be Reginald! “What do they mean by letting you come down here looking like this?” she exclaimed angrily, unmindful of the pathetic faces lifted for a kiss. They had counted so much on Nellie! “I washed my face before I started,” answered Elizabeth, sullenly, while Reginald flushed red and made a saucy lip. Unconsciously Nellie had passed a sponge over a whole slateful of good resolutions. Slowly the four wended their way homeward, and in view of Nellie’s very gloomy expression, Walter felt that any light or jocular allusions to his late telegraphic effort would be wholly out of place. “Do see the flies pouring in!” she exclaimed, fretfully, as they mounted the porch of the house after a long climb through the park. “Easy now!” said Walter. “You’ve got on a little too much steam, Nellie. These are not exactly the affectionate greetings that we were expecting.” Her father came forward gravely and kissed her. “I am afraid they have been making you dreadfully uncomfortable, papa,” she said. “No,” he answered, “they have done very well.” Then, as Reginald and Elizabeth appeared, a little more dishevelled for their climb from the station, he added, “The children are not looking as they should. I wish they were more robust and like other children.” Nellie went upstairs. “Papa never knows when he is comfortable and when he is not!” she said to herself in the glass, when she had reached her room. The next day was spent in putting the house in order. Nellie had a natural gift for making things pretty and attractive, and with a loving recollection of many of her mother’s hints, she pulled down a blind here, bowed a shutter there, brought fresh flowers, and even put up the summer curtains that another hand had left in readiness. Lizzie, too, had come back the evening before—gentle, low-voiced Lizzie, with her brown eyes and close-braided Madonna-like hair. Under her busy fingers the torn and spotted waifs of the day before were slowly restored to their original trim neatness. But when Sunday evening came and Nellie went up to her room to do her packing for the early morning train, she found that she had many things to think of. Pushing aside her valise, after a few moments she blew out the candle and sat down on the window-seat looking out into the moonlit garden. One by one she counted over all her towering ambitions; she rehearsed the successes that the next two years at the seminary were sure to bring her, and weighed not lightly in the balance the friendships and companions of her school-girl life. She felt that her duties in Dulwich would be very fretting, when not tame and uninteresting; she feared that her mind would “utterly rust,” poor child,—and saw herself left hopelessly behind in that race for distinction in which she bad hoped so confidently to engage; but to every objection, with every foreboding, before her memory leaped the picture of the two forlorn, neglected little children who waited for her at the station. This melancholy picture forced her decision. The scent of the budding grapes floated in to her, and, hearing a faint rustle in the garden below, she leaned out. Her father stood upon the steps of his study entrance, his face uplifted and clearly lighted by the full moon which rolled free in the open heavens above the tops of the oaks. With a heavy sigh, he turned to enter the house. “Papa!” she called, softly. “Nellie, are you not in bed yet? It is nearly twelve o’clock.” “Wait a moment,” she said, “I am coming down to speak to you.” Chapter III: Nellie’s “Sacrifices.” Nellie ran downstairs without further reflection. The sight of that lonely figure in the moonlight had crystallized one of those sudden resolutions that often form themselves, perfect and clear, out of what seems to be a chaos of conflicting claims. “Let us walk,” she said. She slipped her hand under her father’s arm, and they turned into one of the shaded garden paths. The flowering shrubs were all in bloom, and the air was full of sweet scents. Far back among the trees a whippoorwill cried in the shadows of the park, and from somewhere at a distance the sound of the voices of young men softly singing in the moonlight floated down to them. “Papa,” said Nellie, “I think that I would rather not go back to school at all, neither now nor next year!” Her father did not answer at once, but appeared to be thinking deeply. “Have you weighed the matter well,” he asked, “for and against?” “No,” said Nellie, with rueful simplicity. “I have only weighed it against.” Her father laughed softly, and Nellie’s heart became lighter at the lately unfamiliar sound. “I do not like to have you give up study at your age. Seventeen is rather early to finish one’s education.” “I shall be eighteen in the autumn,” said Nellie, “and I could study a little at home—not much, though,” she added, after a pause. “But, papa, I am needed. Reginald and Elizabeth will be ruined.” “It is true,” he said, sadly. “They have been like little wild Indians the last month.” “Then may I stay?” “You ask as if it were a favor,” said her father, tenderly. “It may turn out to be so,” she replied, hardly knowing why. “God bless you, dear!” said her father. He stooped, kissed her suddenly, and then turned and walked rapidly up the path. Nellie understood. She was to stay—and a great depression fell upon her. It was a momentous decision; had she made it after due consideration? She waited in the shadow of the woodbines, lost in thought. “After all,” she thought, “perhaps I have been hasty!” The exaltation which had carried her thus far quickly ebbed, and left her stranded in painful irresolution. The sounds from up the path had been growing more distinct. The students often wandered up and down, singing in groups, on the clear summer nights. As this little company passed the house they dropped their voices, and faintly, almost inaudibly, came to Nellie: “And with the morn those angel faces smile

The next afternoon, as Mr. Wharton was starting to get his mail, he met Mr. Cornelius returning. “I thought I saw Nellie a little while ago. Didn’t she get off this morning?” Mr. Cornelius asked. “No; she is not going at all. She wants to leave school.” “Um! What becomes of the lessons?” “Walter suggested that she might prepare to enter college.” “It is not a bad idea.” “As an idea it is not,” replied Mr. Wharton, “but so long as women are not admitted to the college, it might be difficult to carry it out.” “Women are not admitted,” said Mr. Cornelius, “but there is nothing to prevent your letting your daughter attend your lectures on English literature, and I would willingly allow her to come to my class in Greek composition. I think we compare not unfavorably with ‘the competent corps of instructors of the Middletown Female Institute.’” “I hardly think that such a plan would find much favor with the students,” said Mr. Wharton, “and as for Nellie—oh, I do not like to think of her as being so much among them!” “Wharton,” said Mr. Cornelius, “what have you to leave Nellie, if you were to die suddenly?” Mr. Wharton shook his head. “You have nothing or next to nothing,” added his companion, “and out of the munificent stipend granted us by the trustees of Dulwich College you are not likely to save any great sum between now and the time you are sixty. At that age you may be informed that your services are no longer needed.” “Oh, nonsense!” said Mr. Wharton. “When I am sixty I shall be just as able to work as I am now; and as for Nellie, she may be married by that time, and have four children as her mother—” He stopped. “The principle remains the same,” insisted Mr. Cornelius. “If you were to die to-morrow, and if, when you reach the age of sixty, Nellie is not Mrs. Nellie, she will be thrown perfectly helpless on the world. I can’t say that I like the idea of her coming into college classes much better than you do, although if ever there was a girl who could do it with dignity and unconsciousness, Nellie is the girl. But the truth is, you can’t afford to indulge yourself in such squeamishness. You can manage with very little trouble to give Nellie a good education that will make her practically independent, and if you refuse, you do her a manifest injustice.” “You are the last man I should have expected to favor co-education,” said Mr. Wharton. “Then so much the more should you be impressed with the spectacle,” answered Mr. Cornelius, shortly. He hobbled off to his own house, digging his cane deep into the gravel. Mr. Cornelius was lame, and, when excited, he limped more than ever. Mr. Wharton stood and watched him a moment, and then went on his own way. “If he makes up his mind to send Nellie to college, she will go, whether I agree to it or not,” he said to himself, with a soft laugh in which affection and opposition were curiously blended. Reginald and Elizabeth, regarding Nellie’s accession to supreme power with feelings of unmitigated regret, proceeded to take matters with a high hand, displaying that mysterious unanimity which moves small children to do things insubordinate with perfect concord and without previous consultation. Nellie found that, hard as it had been to make the resolution of sacrifice, the effort had been as nothing compared with the daily strain of carrying it out in detail. Those were troublous times, and she often took refuge with her books and papers over upon Mr. Cornelius’ broad piazza. “I can’t make anything of the children,” she said one day, in a discouraged tone. “They are losing all their sweet, charming ways.” “They miss their mother,” Mr. Cornelius answered, lighting his pipe. “I am sure I try my best to take care of them,” said Nellie, with a sigh. “They are always nice and clean and—” “Oh, I don’t mean that! To the masculine eye they are as neat and pretty as ever, but—well, there is something more than raiment, only this time it is not the body. If you leave them to clothe their souls the best way they can, with no help from you, you must not blame them if the garments of their spirit show signs of disarray.” “But I do try to teach them to be well-mannered and polite.” “Do you ever play with them?” “I give them all the time I can.” “It isn’t time they need; it is sympathy.” “But I am not of a sympathetic temperament, Mr. Cornelius.” “You might ‘assume a virtue,’ then. There is Elizabeth—” “I can’t tell what has come over Elizabeth,” Nellie interrupted, impatiently. “She used to be the sweetest little thing, but now—” The pause was eloquent. “I think I shall be compelled to take Elizabeth in hand,” said Mr. Cornelius. “Suppose you send her over to tea with me this evening.” Delighted with the invitation, and wholly unprepared for what was in store for her, poor little Elizabeth was enjoying her strawberries an hour or two later, when Mr. Cornelius, sitting gravely at the hand of the table, casually mentioned that he was sorry she had so completely forgotten her mamma. It is astonishing how a word from an outsider will sometimes effect reforms that home reproof and correction have been powerless to accomplish. For Mr. Cornelius to think that she no longer remembered her mamma! Mr. Cornelius, her best friend! Forgotten? She remembered everything, she passionately assured herself; and late into the night lay with open eyes recalling all that she could of her mother’s teaching and advice. The next morning it was plain to all beholders that Elizabeth had not only turned over a new leaf, but that she intended to have Reginald share in its perusal. “If we only had mamma, Totie,” she said, after some rather severe strictures from Nellie for a bit of carelessness, “if we only had mamma, it would be easier to be good. She never was cross.” “Sometimes she was,” said Reginald. Elizabeth looked at the contrary little fellow with dismay. “Reginald! Your dear mamma! and she is dead!” “She is not dead!” answered Reginald, in a cool voice of conviction. “I see her every night. I go to where she is.” “You don’t! I see you in bed every night. I am awake longer than you are.” “That’s not me,” said Reginald. “That’s my magic self. I leave it there.” “Pooh!” answered Elizabeth. Reginald began to cry. This fiction of going to his mother every night was one of the subterfuges that his proud little heart employed to cheat the wretchedness of reality. “What does she say to you?” asked Elizabeth, relenting at last. “Oh! she takes me up and bounces me”—this was Reginald’s name for being rocked and petted in his mother’s arms—“and we talk about things. She thinks you haven’t been very good lately.” To this home-thrust Elizabeth made no answer, and after a short silence Reginald continued, “Sometimes when I go to her a great beautiful angel comes and takes me. He has black wings; his name is Azarael.” “Oh, I know that angel! Mamma told us about him. Some people call him Death, and are afraid of him.” “But I’m not afraid of him,” said Reginald, “because he takes me to her, and she told me he was kind.” “I remember that time,” said Elizabeth. “Didn’t she tell lovely things?” The child’s eyes filled with tears. Reginald grew slightly pale; his lips twitched but he did not cry. “I don’t like lovely things any more!” he said, out of mere bravado. But Elizabeth was so accustomed to this method of his that she treated his speech as if it had never been made. Fumbling inattentively in her pocket, she drew out a little book bound in some ornamental leather. “Here is my book that she gave me for my birthday,” she said, “and I was to write her a letter in it every day and tell her how my day went. I only wrote one. Nobody’ll ever see it now.” She opened it to the one letter: “April 15, 18—.

“DEAREST MAMMA: This has been such a happy day. Your loving ELIZABETH.”

“I promised to think, and write the exact truth, no matter where she was. I wonder—” Reginald had gone off into a corner to play, and no longer seemed interested. Elizabeth sat down in front of her little desk and gazed fixedly at her book. It had been prepared with care. On the first page her mother’s photograph was inserted. It was a very good one, and the child seemed to draw consolation from the sight of it. Several little mottoes and sentences were written here and there. The first verse in the little book ran: “If thou findest in life anything better than justice, truth, temperance, fortitude. . . . . if, I say, thou seest anything better than this, turn to it with all thy soul!” “Justice, truth; temperance, fortitude.” The little girl remembered how each had been carefully explained, with gay, half-whimsical explanations. “Justice,”—she murmured. “That was not making trouble for other people in the house, not always thinking of myself, not taking Totie’s things when he wants them himself. Truth,”—a little flush followed Truth, and no verbal explanation. “Temperance,—that is not crying myself sick and making myself wretched, and not slamming doors in a rage, or doing anything too much, not writing late. Oh, I know Temperance well enough! I hate it, but I will do it. Fortitude is not making a fuss about hurts, mind hurts or body hurts. I haven’t forgotten that.” Then Elizabeth took up her pen. She trembled a little, and glanced around as she wrote: “June 20, 18—.

“Dear mamma, dear, dear mamma: Now you are an angel you can come and see your children. I shall write in