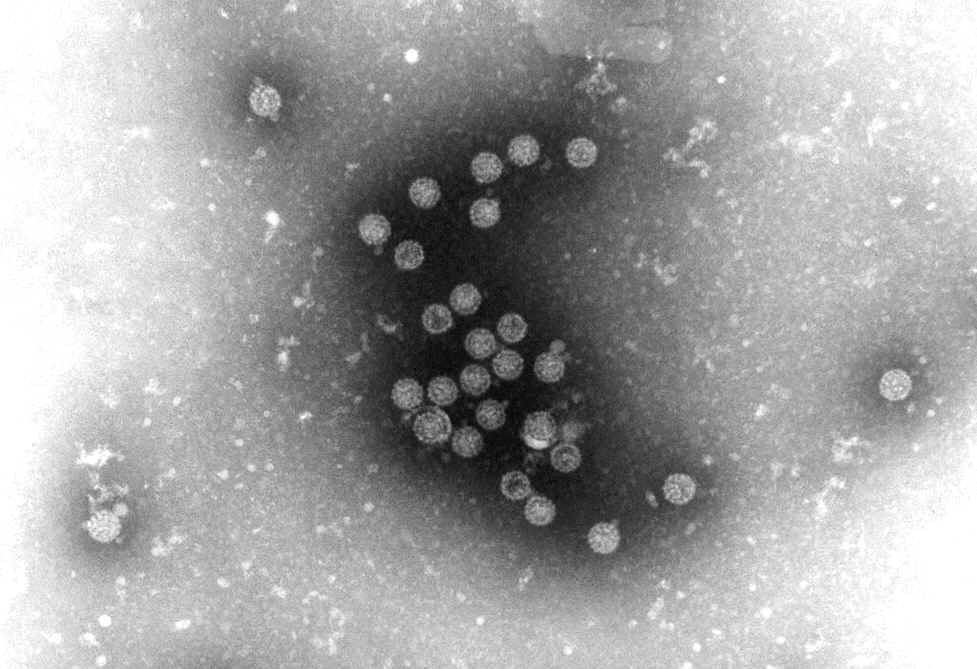

Image of Simian Virus 40 courtesy of the Virology Diagnostic Group,

London.

Used with permission.

Polyomavirus Basics

Polyomaviruses Known to Cause Human Disease

Update 2004-Some New Findings from 2003 and 2004

Links

References

Polyomavirus Basics

Viruses that belong to the family polyomaviridae have circular, monopartite, infectious, double-stranded DNA that exists in a supercoiled structure in the virion and is associated with histones H2a, H2b, H3, and H4 stolen from the host. Both DNA strands code for proteins. The length of polyomavirus genomes is about 5 kilobases. Virions are naked icosahedra with 72 capsomers (both pentons and hexons are pentameric), T = 7, and a diameter of about 45 nm. Polyomaviruses have five to seven proteins, including three capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3, and two proteins, T and t, which are involved in replication of DNA. Transcription is characterized by variable timing of gene expression, with early proteins being involved in replication (though there is no viral polymerase) and late proteins being involved in capsid formation. Varied transcripts are produced through splicing. Replication and virion assembly occur in the nucleus, and virions are released by destruction of the nuclear and cell membranes.

"Polyoma" is derived from the Greek roots poly-, meaning many or much, and -oma, meaning tumors. In keeping with their name, polyomaviruses are known to produce tumors, but interestingly, they do not usually produce tumors in their natural hosts. For example, the polyomavirus Simian Virus 40 (SV40) produces lymphocytic leukemia and reticuloendothelial cell sarcomas in hamsters, but is not oncogenic in monkeys, its natural hosts. Two polyomaviruses are known to cause disease in humans: JC Virus (JCV) and BK Virus (BKV). Both are named after the initials of the patients in which they were first identified. A third polyomavirus, SV40, infects humans but is not known to cause disease.

Until 2000, polyomaviruses were taxonomically classified as a genus in the family papovaviridae. With the publication of the Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, papovaviridae was split into two new families, papillomaviridae and polyomaviridae. Former Humans and Viruses students have laid out the differences and similarities between papillomaviruses and polyomaviruses here.

Polyomaviruses Known to Cause Human Disease

JC Virus (JCV)

Approximately 80% of adults worldwide show serologic evidence of JCV infection, the vast majority without any clinical manifestations or history of JCV disease. Most people are infected in childhood. The route of transmission has not been definitively established, although one possible route is through contaminated food or water. JCV remains latent in the lymphocytes, urogenital tract, and brain of its host and may reactivate to cause disease in immunocompromised hosts.

JCV can cause progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a degenerative disease affecting the oligodendroglial cells in the brain. PML is characterized by development of impaired memory, confusion, disorientation, ataxia, hemiparesis, incoordination, seizures, and/or visual abnormalities. Death usually occurs within 3 to 6 months of onset of symptoms. With HIV, PML is diagnostic of late-stage HIV disease (AIDS). It occurs more often in patients with HIV-induced immunosuppression than immunosuppression for other reasons. There is currently no effective treatment for PML other than attempting to reduce the level of immunosuppression in the patient. Here is some patient-oriented information about PML.

JCV is also associated with hemorrhagic cystitis and nephritis in the immunocompromised. It is thought to be a significant cause of nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients.

BK Virus (BKV)

Approximately 80% of adults worldwide are seropositive for BKV, though there is no evidence that BKV causes disease in the immune competent population. The route of transmission has not been definitively established, although one possible route is through contaminated food or water. (BKV virions are stable in water for weeks.) Another is respiratory spread. BKV remains latent in the lymphocytes, urogenital tract, and brain of its host but may be reactivated if the host becomes immunocompromised.

BKV has been proposed to be associated with kidney, lung, eye, liver, and brain disease. However, there is strong evidence only for BKV's association with hemorrhagic cystitis and nephritis. BKV is especially associated with disease in renal transplant patients, and is thought to cause graft failure in 2-5% of this population. The treatment is to decrease immunosuppression as much as possible without causing rejection; cidofovir may also be somewhat effective. It is important to properly diagnose BKV-associated nephropathy so that appropriate treatment can be given. Here is a case study of BK virus associated nephropathy.

Image of viral inclusions and cellular changes typical of BK polyoma virus

nephropathy are seen in the tubular epithelium of this renal transplant case.

(Jones' Silver Stain,

original magnification X1000)

Used with permission.

Update 2004-Some New Findings from 2003 and 2004

Scientists are beginning to figure out what establishes JCV tissue tropism: These researchers were able to select for a glial cell line resistant to infection by JCV and other polyomaviruses. They then determined that the stage at which viral replication was blocked in these cells was at early viral gene transcription. The next step in this investigation will be to figure out what cellular factors are different in these resistant glial cells than in normal glial cells at that stage of the viral life cycle in order to determine what it is that makes glial cells susceptible to infection by JCV and other polyomaviruses.

Gee GV, Manley K, Atwood WJ. Derivation of a JC virus-resistant human glial cell line: implications for the identification of host cell factors that determine viral tropism. Virology. 2003 Sep 15;314(1):101-9.

The pathway that clarifies the link between HIV and Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy: A team of researchers at Temple University has elaborated on a model that may help explain why PML is seen more often in patients with HIV disease rather than with other immunosuppressive conditions: they showed that HIV-1 Tat protein can induce transforming growth factor beta1 to stimulate specific downstream factors, including Smads 3 and 4, which in turn increase levels of JCV promoter transcription in glial cells. It had been known that Tat increased JCV promoter transcription, but this study helps clarify the pathway by which it happens.

Enam S, Sweet TM, Amini S, Khalili K, Del Valle L. Evidence for involvement of transforming growth factor beta1 signaling pathway in activation of JC virus in human immunodeficiency virus 1-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Mar;128(3):282-91.

Good news for kidney transplant recipients who have lost renal grafts due to BK virus associated nephropathy (BKAN): A small but encouraging study has shown that following loss of a first transplanted kidney to BKAN, 10 patients had successful second transplants. Attention must be given to the possibility of BKAN in these patients, and those showing signs of nephropathy should be treated by decreasing levels of immunosuppression and adding cidofovir.

Ramos E, Vincenti F, Lu WX, Shapiro R, Trofe J, Stratta RJ, Jonsson J, Randhawa PS, Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC, Weir MR, Wali RK. Retransplantation in patients with graft loss caused by polyoma virus nephropathy. Transplantation. 2004 Jan 15;77(1):131-3.

BKV and JCV may sometimes have an etiological role in encephalitis and/or meningitis: This study looked for BKV and JCV in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurological symptoms consistent with meningitis or encephalitis. They found an increase in the percentage of symptomatic patients positive for BKV (3.8%) and JCV (1.5%) over the controls. Their study indicates that there is a possibility that BKV and JCV are associated with some cases of meningitis and encephalitis in both immunocompromised and immune competent patients. Clearly, though, this data is more suggestive than definitive and more studies are needed. Also clearly, BKV and JCV didn't explain most of the cases of encephalopathy and meningitis that they saw in this study.

Behzad-Behbahani A, Klapper PE, Vallely PJ, Cleator GM, Bonington A. BKV-DNA and JCV-DNA in CSF of patients with suspected meningitis or encephalitis. Infection. 2003 Dec;31(6):374-8.

Initial development of a possible new treatment for BKAN: This study took dendritic cells from the blood of both healthy and immunocompromised patients and activated them with inactivated BK virus. These cells were then used to activate cytotoxic T cells (CTL) in culture. Subsequently, the CTL were shown to lyse BKV-infected cells at a much higher rate than the controls for both groups. This same process might be able to be used to improve renal transplant patients' immune systems' ability to suppress BKV disease after transplantation by infusing them with autologous BKV-specific CTLs either prophylactically or in response to signs of BKV disease.

Comoli P, Basso S, Azzi A, Moretta A, De Santis R, Del Galdo F, De Palma R, Valente U, Nocera A, Perfumo F, Locatelli F, Maccario R, Ginevri F. Dendritic cells pulsed with polyomavirus BK antigen induce ex vivo polyoma BK virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell lines in seropositive healthy individuals and renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003 Dec;14(12):3197-204.

Links

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Database page for polyomaviridae: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ICTVdb/Ictv/fs_polyo.htm

Humans and Viruses student pages from past years:

1998

1999

2000

2002 (currently a dead link)

References

Bofill-Mas S, Formiga-Cruz M, Clemente-Casares P, Calafell F, Girones R. Potential transmission of human polyomaviruses through the gastrointestinal tract after exposure to virions or viral DNA. J Virol. 2001 Nov;75(21):10290-9.

The Centers for Disease Control's 1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded of Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm

Flint SJ, Enquist LW, Krug RM, Rancaniello VR, Skalka AM. Principles of Virology: Molecular Biology, Pathogenesis, and Control. Washington: ASM; 2000.

Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields Virology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001.

Ryan KJ, Ray CG. Sherris Medical Microbiology: an Introduction to Infectious Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

Created by Bliss Temple, March 2004for Human Biology 115A: Humans and Viruses

Professor Robert Siegel

Stanford University