Collagen / Hyaluronic Acid Matrices

for Connective Tissue Repair

Eric E Sabelman PhD, Nicole Diep MS, ¹

William Lineaweaver MD ²

¹VA Rehabilitation R&D Center

3801 Miranda Ave., MS-153

Palo Alto, CA 94304

²

Stanford University

Division of Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery

Medical School, M/C 5560

Stanford, CA 94305

Abstract

Subcutaneous tissue loss from pressure sores or trauma is commonly treated

by reconstructive surgery, using a myocutaneous flap rotated from an adjacent

unaffected site. This is a preliminary report on a semi-synthetic graft

intended to perform the same function as the surgical flap but without donor

site morbidity; it should have the same properties as lost tissue and contain

autologous cells. We are studying composites of Type I bovine or rat collagen

with hyaluronic acid (HyA).

Three physical forms of 1:1 collagen:HyA have been made:

- (1) homogeneous dispersions of HyA particles,

- (2) continuous-strand esterified HyA mats or felts,

- (3) loosely-packed HyA ester beads.

Physical properties were assessed by a sphere indentation test for creep

compliance and a tensile relaxation test using sutured junctions simulating

clinical use. Creep (combined compression and shear) and tensile moduli were

lower but comparable to published values for rabbit mesentery including effects

of pre-loading history and continued creep over long periods (>16 hours).

Early (<2 minute) indentation is influenced by a collagen-rich surface

layer. Cell interaction: Rat cells were added in the form of: neonatal

fibroblasts layered onto the matrix, adult omentum explants inset into the

matrix, and adult fibroblasts and adipocytes distributed throughout the matrix.

Cell survival and attachment were assessed after 7-14 days by vital staining

and post-fixation histology. Survival was poor (<50%) in homogeneous

collagen:HyA, due to residual solvent in the HyA. Cells migrating from explants

tended to envelop individual HyA beads or strands. Surface cells entered the

matrix principally along flaws in the collagen phase. HyA prevented contraction

seen in cell-seeded collagen-only preparations. Matrices of stranded HyA with

cells distributed in the collagen phase have better strength and surgical

handling, and are being pursued further.

Return to Contents

Problem

Pressure sores ("decubitus ulcers") occur in hyposensitive skin of

immobilized individuals, where prolonged compression of tissue between the

supporting surface and a bony prominence impairs capillary blood perfusion in

the region 1 . Sufferers typically include

paralyzed spinal cord injured and stroke patients, postsurgical and casted

fracture patients, and frail institutionalized elderly 2 . It is estimated that every year 7% of the 200,000

spinal cord injured persons in America will develop an ischial pressure sore.

Additionally, 14% of the general population over 70 years of age will develop

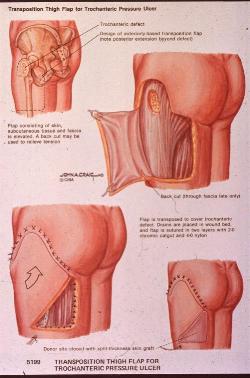

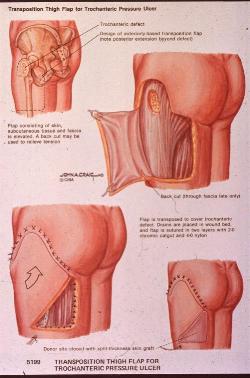

pressure sores. Between 3 and 8.8% of sores will require surgery 3 [Figure 1].

|

| Figure 1 - Pressure sore surgery |

Recurrence rates after surgery vary from 7% in trochanteric ulcers to 11% of

sacral sores 4 ; recurrence is frequently due to

continued stress on deep tissues despite adequate skin coverage. All pressure

sores are difficult to treat; failed surgeries result in some of the longest

hospital stays (>70 days on average) and highest costs.

Conservative dressings: The range of nonsurgical approaches to enhance

healing of open pressure sores has recently broadened. Gauze dressings have

been superceded by a variety of packings (usually based on sodium alginate

5 ) and film barriers for controlling moisture

content of the wound environment while excluding contamination. Collagen

6,7,8

and collagen:HyA 9 have been investigated as

dressings, but without tailored microgeometry to encourage incorporation into

living tissue.

|

| Two-phase collagen:hyaluronic acid composite

tissues |

Reconstructive surgery using prefabricated flaps: Since restoration and

maintenance of vascular continuity within any flap is essential to its

survival, prefabrication is used to either place a larger vessel within tissue

to be transferred or to prepare a donor site in advance, thus achieving in a

single procedure what would otherwise require multiple operations 10 . Experimentally, synthetic biomaterials have been

combined with mobilization of a vascular pedicle, which accelerates ingrowth of

connective tissue into the synthetic graft 11.

Similar concepts have been explored by Walton and Brown 12 , with vascular pedicles to accelerate

vascularization of Teflon discs, and Mikos and co-workers 13 , who implanted polylactic acid discs into folds in

the rat mesenteric membrane.

Return to Contents

Objectives

We hypothesize that a cell-seeded synthetic matrix could perform some of the

functions of the myocutaneous flap autograft, specifically:

- Restore connective tissue depth and contour better than a skin graft

- Restore mechanical properties for protection against vascular stasis under

load

- Restore viable tissue more rapidly than healing by peripheral ingrowth

The success of the tissue-engineered graft would be enhanced by:

- Rapid revascularization

- Reducing the magnitude of the interfacial barrier between graft and wound

bed, so as to prevent fibrous encapsulation

The immediate goals reported in this paper are to:

- Fabricate tissue matrices having properties approximating subcutaneous

connective tissue

- Examine interaction of these matrices with cells in vitro

- Implant matrices with a vascular pedicle into animals and retrieve after 3,

5, and 8 weeks

Return to Contents

Approach

The graft is constructed of a biopolymer matrix inoculated with fibroblasts

and/or epidermal cells and is either microsurgically reconnected to blood

vessels near the wound, or perfused with a culture medium in lieu of blood

circulation.

The matrix consists of collagen, which provides a substrate for cell

attachment, and hyaluronic acid, which provides bulk, viscous damping and

compression resistance without impeding cell mobility 14 , similar to fat in the intact tissue. Collagen is

an appropriate material for such matrices, since it is a structural protein

with minimal interspecies immunoreactivity and capable of dissolution and

controlled repolymerization 15 .

|

| Figure 2 - HyA:collagen matrix |

|

Three physical forms have been created [Figure 2]:

- homogeneous 1:1 collagen:HyA dispersions of random-geometry HyA particles

- continuous-strand HyA mats or felts

- loosely-packed HyA beads

Note that because HyA is in the form of a discrete micron-scale phase, it

does not interact with collagen at the molecular level as in cartilage 16 , nor is it free to flow under load 17.

|

Return to Contents

Methods 1

The matrices under investigation were mixtures of Type I collagen (from

bovine skin or rat tail tendon) with hyaluronic acid (supplied in 1:9 DMSO

solution). Collagen (1-2% in pH 3.5 acetic acid, neutralized by mixing 1:1

Hanks BSS + stoichiometric NaOH) was added to preformed HyA bead or strand

preparations and allowed to polymerize in situ in 35-100 mm Petri dishes.

Cell-free matrices were cross-linked by UV illumination (254 nm, ¸ 200

mw/cm2) to avoid cross-linking agents such as glutaraldehyde known to have

cytotoxic effects 18 .

| Homogeneous Collagen/HyA - Foams of Type I collagen are produced

by neutralizing the acid collagen solution and homogenizing to disperse

entrapped air and CO2 formed during neutralization into micron-scale bubbles.

The homogenized collagen is mixed at various ratios with 5% HyA in DMSO using

the same method but lower shear forces, then is layered into a Petri dish and

allowed to polymerize or gel in situ for two hours at 37· C. The

microbubbles dissolve and are replaced by liquid over the course of a few days,

leaving a porous fluid-filled microstructure.

Collagen/HyA bead matrix - Droplets or beads of hyaluronic acid are

formed in an immiscible liquid using extrusion nozzles driven by a

low-frequency oscillator. The beads are uniform in diameter (50 µm - 1

mm) and therefore incite minimal foreign-body reaction compared to dispersions

formed by sonication[Figure 2b]. Similar methods are used for

microencapsulation of cells for suspension culture and xenogeneic

transplantation 19 .

|

|

| Figure 2b- Collagen/HyA bead matrix - |

|

|

| Figure 3a - -Beaded HyA:collagen |

|

Packing density of the beads [Figure 3a] is such that spaces between them

permit immigration of cells from an inoculum or the periphery of the

wound. |

|

| Figure 3b - Collagen/HyA felt matrix |

|

Collagen/HyA felt matrix - Fibers or strands of HyA are made by

extrusion into a bath (e.g.: absolute ethanol) that is miscible with the DMSO

solvent but immiscible with HyA [Figure 3b]. |

|

| Figure 4a - Stranded HyA:collagen |

|

Prolonged soaking (2-7 days) in a similar bath results in condensed HyA

strands that have high tensile strength and resistance to rehydration compared

to bulk HyA [Figure 4a].17. |

|

| Figure 4b - Stranded HyA:collagen |

|

The soaking bath is removed by filtration and washing with distilled water;

this and mechanical treatment to interlock the strands yields a felt or mat 1-2

mm thick with interstices between strands of 50 µm to several mm [Figure

4b]. |

Return to Contents

Methods 2

Donor Cells - For in vitro testing, tissues were

obtained from neonatal or young adult Fisher rats. Specimens were dissected

using aseptic microsurgical technique into deep and superficial components,

then enzymatic or immunoadhesion techniques were used to separate epidermal

cells, fibroblasts, adipocytes and/or myoblasts. For clinical use, autologous

cells would be obtained from the wound margin or from biopsy of soft tissues

remote from the injury site.

|

| Figure 5 - Explant culture in wells or dishes |

In Vitro Culture Model - Cells were cultured on experimental

matrices in either static Petri dishes [Figure 5] or in perfused chambers

[Figure 6]. After expanding cell population in culture, cells were suspended in

DMEM + 10% FBS and added at concentrations of 500-2000 cells/mm3 of matrix. In

some static cultures cells were layered onto the matrix in the same dish in

which it was gelled; for replicate cultures, the matrix was cut into 1 cm

squares and distributed among 4-8 wells or dishes.

|

| Perfusion circuit for in vitro test |

Perfused cultures were in molded silicone chambers with a 25 mm square

cavity; passing through the midline of the 5 mm depth of the cavity were

parallel polysulfone hollow ultrafiltration fibers through which culture medium

(DMEM + 5% FBS) was pumped at 2 ml/min [Figure 6].

|

| Figure 6 - Perfused silicone chambers |

One or two layers of matrix were placed on each side of the row of hollow

fibers before sealing the chamber between aluminum plates. Cells were

inoculated by injection through the silicone chamber wall. In vitro cell

survival and attachment were assessed after 7-14 days by vital neutral red

staining and post-fixation thin section histology with hematoxylin-eosin

staining. Relative cell population was estimated by comparing area occupied by

cells in and perpendicular to the plane of the matrix layer, with cell-culture

plastic as a control substrate. Matrix geometry was evaluated in compressed

whole mounts stained for collagen with Sirius red F3BA and for HyA with alcian

blue.

Return to Contents

Methods 3

Surgical implantation - Male F344 Fischer rats weighing

approximately 400 grams were anesthetized with intraperitoneal sodium

pentobarbital. All surgical repairs and dissections were performed under a

Zeiss operating microscope with 10X to 25X magnification. A 25 - 30 mm square

patch of skin over the abdominal region was shaved, incised on 3 sides and

elevated HyA strand or bead-containing matrix layers were cut to 20 - 25 mm

square, then laid in place and attached to muscle fascia with 2 or 3 4-0 nylon

sutures. The arteriovenous pedicle was constructed from the saphenous vein

dissected from one leg, looped over the deep matrix layer, and anastomosed to

the femoral artery. Sufficient collateral veins exist so that circulation to

the leg, although initially decreased, is not static. One or more layers of

matrix were laid over the vascular loop before closing the incision with wound

clips.

Rats were sacrificed and the implant region was excised and fixed at 3, 5

and 8 weeks post-surgery. Paraffin sections were cut at 6 to 8 µm and

stained with hematoxylin-eosin to evaluate inflammatory reaction, and with

Masson's or Gomori's trichrome for connective tissue. Because HyA was not

infiltrated with paraffin, displacement and folding of HyA in sections could

not be avoided. Light microscopy was used to visualize: presence and

orientation of blood vessels, location and morphology of cells, orientation and

density of the extracellular matrix, location of specific matrix components

dimensions of voids within the matrix, adhesion to the surrounding tissue, and

extent of biodegradation of the matrix.

Return to Contents

Methods 4

Mechanical Testing - In order to compare synthetic matrices

with host site tissue and with published values for similar materials, physical

properties were assessed by a sphere indentation test for creep compliance, and

a tensile stress relaxation test using sutured junctions simulating the

clinical application.

|

| Figure 7a - Sphere indentation compression test |

|

Both tests were performed at ambient temperature and humidity.

In the sphere indentation test [Figure 7a], layers of matrix 15 mm in

diameter were stacked on a glass slide to achieve 6-7.5 mm depth. A steel

sphere (1/8 to 7/16 inch diameter stainless ball bearing) was gently placed on

the matrix, and the rate and distance it sank into the matrix were measured on

a video image at 15X magnification. A time-dependent compression modulus, E(t),

was calculated from:

|

|

2 (1-µ2) P

E=------------

_ 2Rh-h2

|

where µ is Poisson's ratio (=0.5), P is the total force generated by the

sphere's weight, R is the sphere's radius, and h is the depth of indentation at

time t. This rudimentary calculation takes into account the change in surface

stress as contact area increases, but assumes internal stresses in the matrix

are roughly equivalent to a flat indentor and ignores effects of finite

thickness 20 . Samples of previously-frozen rat

abdominal fat and skeletal muscle were tested by the same method. |

|

| Figure 7b - Tensile stress relaxation test |

|

Tensile tests were conducted on 10 x 25 mm

samples typically 2 mm thick [Figure 7b]. Monofilament polypropylene suture

(4-0) was used to make 3 or 4 stitches in each end; the upper end was tied to a

beam attached to one arm of a Cahn microbalance. After taring the balance, the

other end was fixed to a 20 gram weight on an elevating stage. Weights (1-14

gram) were added to the opposite arm and the balance was re-leveled by lowering

the stage a measured distance. Stress relaxation was measured by nulling the

balance at intervals during a 10-180 minute period. Tensile modulus was

calculated assuming a constant cross-section. The same apparatus can be used

for suture pull-out tests, which typically require forces greater than 20

grams.

|

Return to Contents

Results 1

Matrix Geometry - Sections of homogeneous collagen:HyA

matrices showed that HyA was uniformly dispersed in the form of sharp-edged

laminated particles less than 200 µm, typically 20-50 µm, in

diameter.

| Missing figure - fig8.jpg

|

| Figure 8 - HyA strands under tension relative to collagen

gel |

|

HyA strands were 100-200 µm diameter and in compressed whole

mounts were interlaced and effectively coated with collagen. The stiff HyA

strands were subject to residual bending stress, as seen at cut edges where

they spring out of the surrounding collagen gel [Figure 8]. HyA beads were

0.5-1.0 mm diameter and sparsely distributed, separated by 2 or 3 diameters of

collagen gel.

|

|

| Figure 9 - Cells penetrating defects in collagen

phase |

|

Cell growth - Cells were initially concentrated at the surface

of matrices, and over the first week of culture penetrated into defects in the

collagen phase [Figure 9]. Neither cells nor collagen adhered to HyA beads

other than by mechanical entrapment.

|

|

| Figure 10 - Cells migrating through collagen phase in

vitro |

|

Populations of cells migrated through the collagen phase without

directly contacting the HyA phase [Figure 10]. Unconstrained pure collagen gels

are known to contract under the influence of cell-generated tensile forces;

this did not occur in HyA-containing matrices. Passage of cells completely

through the matrix was avoided in perfused cultures by turning the chamber over

once a day. Such leakage of cells seemed more prominent in regions with sparse

HyA fibers. While quantitative cell viability tests were not conducted, fewer

cells survived on or in homogeneous collagen:HyA preparations compared to

matrices containing pre-formed HyA or to tissue-culture plastic.

|

|

|

|

|

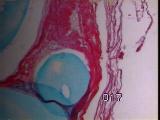

Figures 11a,b,c - Implant at 3 weeks: neovascularization, collagenolysis

In vivo implantation - Inflammation was minimal, with rapid capillary

outgrowth into the matrix within 3 weeks, accompanied by evidence of

collagenolysis [Figure 11].

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figures 12a,b,c - Implant at 5 weeks: acute inflammation subsided

At 5 weeks, acute inflammation had subsided, although chronic inflammatory

cells were present [Figure 12].

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figures 13a,b,c - Implant at 8 weeks: HyA component largely intact

At 8 weeks, most of the original collagen had been replaced by fibrous

connective tissue, while the HyA component was largely intact [Figure 13]

vascularity was reduced.

|

|

| Figure 14 - Cells enveloping individual HyA beads or

strands |

|

As predicted from in vitro cell ingrowth experiments, migrating cells

enveloped individual HyA beads or strands, and did not form a fibrous capsule

around the entire implant [Figure 14].

|

|

| Figure 15a - Vascular pedicle, cross section |

|

The collagen phase was nearly all resorbed by 8 weeks; in contrast,

most HyA beads or strands were intact [Figure 15a]. Foreign body giant cells

were present, but rare, adjacent to HyA surfaces. Individual HyA strands or

beads became encapsulated by a 3 - 4 cell thick layer.

|

|

| Figure 15b - Vascular pedicle, longitudinal

section |

|

The vascular pedical was evident in both cross [Figure 15a] and

longitudinal section [Figure 15b]. The abdominal site did not provide a wound

margin suitable for testing integration.

|

Return to Contents

Results 2

Mechanical Properties -

Return to Contents

Discussion

|

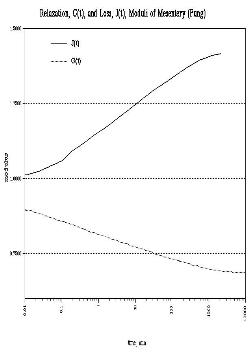

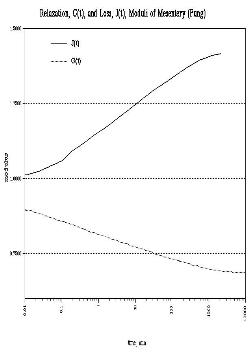

| Figure 19 - Creep & relaxation moduli of rabbit

mesentery (Fung [23]) |

|

Material properties of soft tissues tested as controls were

comparable to published values for similar tissues (Fung22,23) gives tensile creep and

relaxation moduli for rabbit mesentery, noting that a known pre-loading history

is essential to derivation of repeatable elastic constants, and that over

extremely long periods (¸103 minutes) soft tissues may exhibit unlimited

strain [Figure 19].

This effect is evident in the approximation of indentation to an inverse

power function with respect to time. In our specimens, the early (<2 minute)

curve is most likely due to the collagen-rich surface of the collagen:HyA

composite. Only after the stress field generated by the sinking sphere reaches

the intermeshed HyA strands does this component alter the apparent modulus.

|

|

|

In a study of cell-seeded collagen sponges, Jain, et

al., 24 conducted a tensile test of samples with and without

cells. Stress/strain curves were comparable up to 50% strain [Figure 20].

. Healing of tissue is hypothesized to be accelerated by implantation of a

synthetic tissue having the same chemical and structural properties as the lost

tissue and inoculation of the implant with autologous cells. This concept is

based on two premises: (1) that the human body lacks in maturity geometric and

biochemical cell guidance information present in the embryo, which may be

provided by an artificial extracellular matrix, and (2) that a completely inert

biomaterial lacks the capacity to integrate with intact tissue and respond to

functional demands, provided by a cellular component.

|

The general concept of facilitated regeneration through the use of composite

artificial/cellular tissues has broad applications beyond the current clinical

uses in skin repair and experimental use in peripheral nerve grafts. The

pressure sore is a good model for this concept since it is localized,

accessible without internal surgery and non-critical to immediate survival. The

in vitro test is in fact a worst-case approximation of an avascular

injury site, and if cell growth occurs as desired in vitro, growth

should be as good or better in vivo.

Return to Contents

Acknowledgements

Histology performed by Min Hu, MD PhD; Graphics support by Betty Troy.

Funding by VA Rehabilitation R&D pilot projects B92-476AP, B1389-AP;

in-kind support by Stanford Div. of Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery

Return to Contents

|

References

|

1. |

Vidal, J., Sarrias, M., "An analysis of the diverse factors concerned with

the development of pressure sores in spinal cord injured patients",

Paraplegia, 29: 261-267, 1991. |

2. |

Staas, W.E. Jr., LaMantia, J.G., "Decubitus ulcers and rehabilitation

medicine", Int J Dermatol, 21: 437, 1982. |

3. |

Allman, R.M., Goode, P.S., Patrick, M.M., Burst, N., Bartolucci, A.A. Pressure

ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation.

JAMA, 273(11): 865-870, 1995. |

4. |

Rogers, J., Wilson, L.F., "Preventing recurrent tissue breakdowns after

'pressure sore' closures", Plast Reconstr Surg, 56: 419,

1975. |

5. |

Chapuis, A., Dollfus, P., "The use of a calcium alginate dressing in the

management of decubitus ulcers in patients with spinal cord lesions",

Paraplegia, 28: 269-271, 1990. |

6. |

Marzin, L, Rouveix, B., "An evaluation of collagen gel in chronic leg

ulcers", Schweiz Rundschau Med (PRAXIS), 71: 1373-1378,

1982. |

7. |

Leipziger, L., Glushko, V., Nichols, J., DiBernardo, B., Shafaie, F., Noble,

J., ALvarez, O.M., "Dermal wound repair: The role of collagen matrix

implants and synthetic polymer dressings", J Am Acad Dermatol,

12: 409-19, 1985. |

8. |

Doillon, C.J., Whyne, C.F., Brandwein, S., Silver, F.H., "Collagen based

wound dressing: Control of the pore structure and morphology", J Biomed

Mater Res, 20: 1219-28, 1986. |

9. |

Doillon, C.J., Silver, F.H., "Collagen based wound dressing: Effects of

hyaluronic acid and fibronectin on wound healing", Biomaterials,

7: 3-8, 1986. |

10. |

Khouri, R.F., Upton, J., Shaw, W.W., " Principles of flap

prefabrication", Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 19(4): 763-772,

1992. |

11. |

Lineaweaver, W., de la Pena, J.A., Briones, R., Yim, K., Newlin, L., Buncke,

H., "Muscle transplantation in the rat" Studies of the latissimus

dorsi, serratus anterior, combined latissimus serratus, and gracilis",

Proc 3rdVienna Muscle Symp <03, 1990>, G. Freilinger & M.

Deutlinger, eds., (Blackwell, Vienna), 3: 9-12, 1992. |

12. |

Walton, R.L., Brown, R.E., "Tissue engineering of biomaterials for

composite reconstruction: an experimental model", Ann Plast Surg,

30: 105-110, 1993. |

13. |

Mikos, A.G., Sarakinos, G., Lyman, M.D., Ingber, D.E., Vacanti, J.P., Langer,

R., "Prevascular-ization of porous biodegradable polymers",

Biotechnology Bioengineering, 42: 716-723, 1993. |

14. |

Larsen, N.E., Pollak, C.T., Reiner, K., Leshchiner, E., Balazs, E.A.,

"Hylan gel biomaterial: dermal and immunologic compatibility", J

Biomed Mater Res, 27: 1129-34, 1993. |

15. |

Sabelman, E.E.: "Biology, biotechnology and biocompatibility of

collagen", chapter 3 in: Biocompatibility of Tissue Analogs, v.

I, D.F.Williams, ed. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL), pp. 27-66, 1985. |

16. |

Scott, J.E., "Proteoglycan-fibrillar collagen interactions",

Biochem J, 252: 313-323, 1988. |

17. |

Gibbs, D.A., Merrill, E.W., Smith, K.A., Balazs, E.A, Rheology of hyaluronic

acid. Biopolymers, 6: 777-794, 1968. |

18. |

van Luyn, M.J., van Wachem, P.B., Damink, L.O., Dijkstra, P.J., Feijen, J.,

Nieuwenhuis, P., "Relations between in vitro cytotoxicity and crosslinked

dermal sheep collagens", J Biomed Mater Res, 26(8):

1091-1110, 1992. |

19. |

Wolters, G.H.J., Fritschy, W.M., Gerrits, D., Schilfgaarde, R. van., "A

versatile alginate droplet generator applicable for microencapsulation of

pancreatic islets", J Applied Biomater, 3: 281-86,

1992. |

20. |

Timoshenko, S., Goodier, J.N. Theory of Elasticity, 2nd ed. (New York:

McGraw-Hill), pp. 366-377, 1951. |

21 |

Guidry, C., Grinnel, F., "Contraction of hydrated collagen gels by

fibroblasts: Evidence for two mechanisms by which collagen fibrils are

stabilized", Collagen Rel Res, 6: 515-529, 1986. |

22. |

Duck, F.A., Physical Properties of Tissue (London: Academic Press), pp.

151-160, 1992. |

23 |

Fung, Y.C., Bio-viscoelastic solids, ch. 7 in: Biomechanics: Mechanical

Properties of Living Tissues (New York: Springer-Verlag), pp. 106-260.

1981. |

24 |

Jain, M.K., Chernomorsky, A., Silver, F.H., Berg, R.A., Material properties of

living soft tissue composites. J Biomed Materials Res, 22(A3):

311-326, 1988. |

Return to Contents

|