Analog-2 - Digitization

Q: why does digital transmission work better?

Q: why are digital copies flawless?

Digitization - Samples - A/D Converter

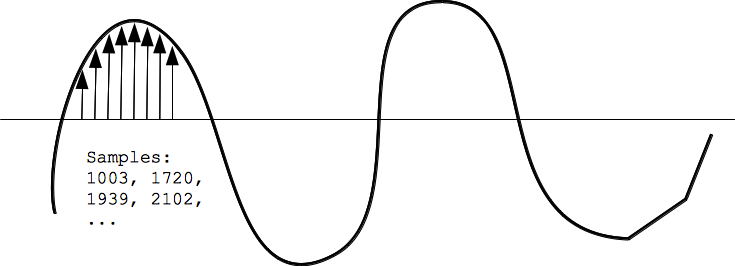

The way an analog signal is brought into the computer is "digitization". The computer "samples" the signal very rapidly over time, noting the value (the height basically) of the curve each time, and recording that value as a number. CD quality audio samples the sound signal 44000 times per second, noting the "height" of the sound signal once for sample. Each sample is a whole number in the range -32768 .. 32767 (this is the range of number that can be stored in 2 bytes, 256 squared).

Audio CD digitization is very good, but not perfect. The signal might have a little wiggle that happens so fast, the 44000 samples/second are not fast enough to quite capture the wiggle perfectly. In reality, 44000 samples per second captures almost everything the human ear can hear anyway. There can also be a sort of rounding error -- the signal value might be in between 1452 and 1453, and the digitization has to pick just one value to represent it. As a practical matter, the 44000 samples per second is extremely good at capturing the level of detail that humans can hear.

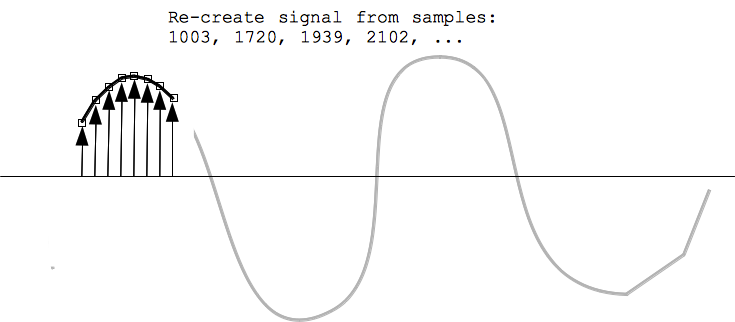

So in essence, digitization translates a sound signal into just a series of numbers: 12000, 12002, 12006, 12007, 12010, 12005, 12006, ... and so on. Playing back the digital sound is just the reverse: a chip takes in the stream of numbers, say representing 44000 samples/second, and constructs an electrical signal that matches those numbers over time. In effect, this reconstructs the original sound signal from the numbers.

Digital Playback - D/A Converter

Digital vs. Errors

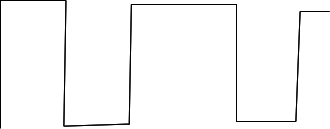

Read back digital signal, ideal, 0/1:

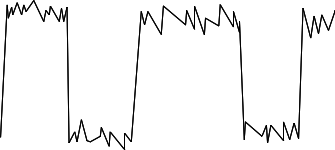

Read back digital signal in reality, with noise:

For CD audio, each sample number (12000, 12002, 12006, 12007, 12010, 12005, 12006, ...), is coded as a series of 0's and 1's on the disk. (A single number can recorded as a pattern of 0's and 1's, but we have not gone into the detail of how it's done.) Say, a dark spot on the disk is a "1", a light spot is a "0". Now to play the CD, the player reads back this signal with the 0/1 information on it. As above, reading back a signal, you tend to get noise/hiss. In this case, even with lots of noise on the signal, the player can almost always distinguish the 0's from the 1's. It assembles the 0/1 values, from that gets back the sample values (12000, 12002, 12006, ...) and from that reconstructs the sound signal. The key step here, recording the samples as 0's and 1's, is that the read-back process is very resistant to noise. In contrast, with the analog system, the noise is mixed in with the signal we want. With digitization, we screen the noise out.

As a second layer of error-correction, the CD stores in a sense, redundant copies of the sample data. So if one section has errors, detected with a checksum scheme, the CD player can switch to use an alternate copy. This is how, even with a small hole drilled in it, in theory a CD player can still play back perfectly. This is another example of an advantage we get by moving the sound data to the digital domain of just numbers.

Theme - Digitization is an Enabler

Example Digital Amplitude - You Try It

Example Digital Compression Lossless

Example Digital Compression Lossy

With this picture of a signal digitized into a series of sample numbers, you can understand a bit how compression works. For audio, the samples tend to look like this: 12000, 12002, 12006, 12007, 12010, 12006, 12005.

As a practical matter, each sample number tends to be very close to the sample numbers that come just before and just after it in time. So one way to "compress" the audio, so it takes up less space, is to record just the changes -- for each sample, record how much change it is from the previous sample. So the above looks like 12000, +2, +4, +1, +3, -4, -1. These change numbers tend to be small, so it turns out they can be recorded more compactly (requiring fewer 0's and 1's). This is nice example of digital compression -- recording the data in a way which takes up less space, but you can still recreate the original signal. In this case, the compression is lossless.

Having translated the audio into the digital domain -- a series of sample numbers -- we open the data up to all sorts of computer manipulations, since computers are cheap and effective at manipulating numbers. MP3 is another example of audio compression. MP3 is complicated, reducing the space required by 10x, and also it is lossy, so it discards little bits of the original signal in a way which the human auditory system tends not to notice.