This article will be revised as I receive more information on Young. If you or anyone you know has details not presented here, please Greta de Groat.

Young the StarAt one time, Clara Kimball Young was the most popular movie star in America. In 1914 she polled ahead of Mary Pickford, and was the first film star to have her name in lights on Broadway. She was so well known that her name continued to be recognized for decades after her last starring films. Yet she is little regarded by film aficionados today, though most of her existing films are readily available. Unfortunately, even those films represent but a small portion of her work, and all of the films from the middle of her career, 1916 (except for a fragment) to 1918, are lost.

Clara Kimball Young was a tallish woman of mature appearance, even in her earliest screen appearances. She had a plain but expressive face with large round dark eyes for which she was famed, and long dark hair. Her type of looks were highly admired in the 1910's, though, and she was regarded as a great beauty. She had the robust figure of many stars of her day and was inclined to be matronly in her later starring years. Still, she wore stylish clothes well and they became an increasingly important part of her films.

|

|

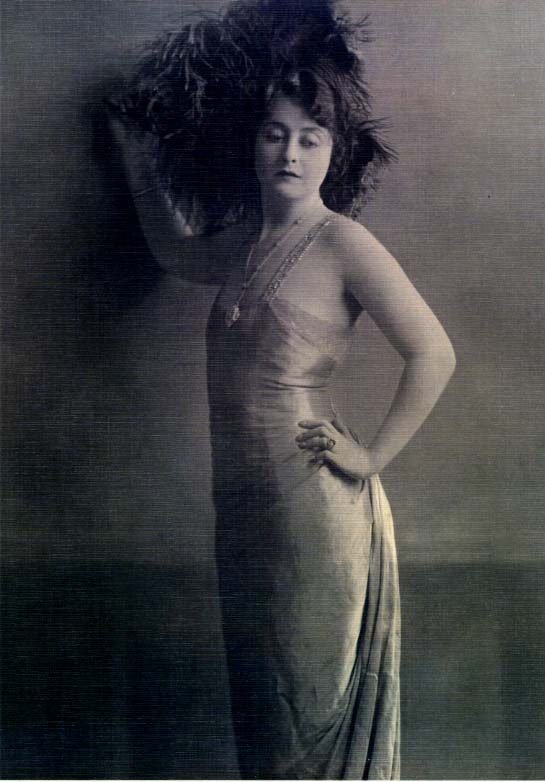

| Young during her Select days Photo by Alfred Cheney Johnston |

A naturally ebullient personality (Frances Marion described her as " as effervescent as charged water"), she is best remembered as the star of heavy-breathing dramas. The types of roles she played are varied and interesting. Though she played her share of virtuous, put-upon heroines a la Norma Talmadge, her characters more often took an active role in their fate. Sometimes they acted out of strength of character or purpose, sometimes from weakness. Frequently she triumphs, occasionally she makes a bad decision and suffers the consequences. She rebels against her parents, argues with her husbands, defies the civil authorities, jumps bail, overcomes odds to become a professional musician. She's usually a wife or would-be wife, but may also be a singer, shopgirl, shop owner, singer (several times), spy, detective, faith healer, terrorist. For some reason, though, she is very rarely a mother, usually a mainstay of women's dramas. She is generally a competent actress, but has her limitations and virtue was one of them. Her saintly characters are her dullest and least convincing. In fact, Young is at her best when she is at her worst--angry, argumentative, petulant, duplicitous, flirtatious. She is also a talented comedienne. She uses a very gestural acting style with much arm movement and eye-widening. A particularly expressive mouth that naturally turned down at the corners gave her expressions of distress a particular urgency. One bad habit, though, is her use of a blank, wide eyed stare to service for states as diverse as seriousness of purpose, hypnotic trance, and blindness. Her style of acting, widespread in the teens, came to seem increasingly old fashioned in the 20s when her career was waning.

Young was born September 6, 1890 (later given as 1893) in Illinois. She usually gave Chicago as a birthplace, but the Cook County Offices have no birth record of anyone of that name between 1871 and 1916. Her parents, Edward M. Kimball and Pauline Maddern (nee Garrett), were traveling stock actors with the Holden Company, and she may have been born on the road. She and her parents were censused in 1890 and 1900 in Benton Harbor, Michigan, where her name is given first as Clarisa, then as Clairee. In one article she says her name was Edith, but was changed in childhood to Clara by her relatives in Benton Harbor, with whom she stayed while attending grade school. Judging from the census information, however, this does not appear to be the case. She made her stage debut at age three, and during her early years traveled with her parents and acted child parts with the company. She attended St. Francis Xavier's Academy in Chicago and then was hired into stock companies and went back out on the road playing, in among other places, mining towns in Nevada and an extended stay in Seattle (the latter performances are listed in the book "Silent Film Stars on the Stages of Seattle" by Eric L. Flom). At some point not made clear in published accounts, she met and married actor James Young. As the story goes, he showed her picture to the Vitagraph brass, who offered her a yearly contract at Vitagraph for $25 a week. At the time she was in Philadelphia making $75 a week, but since Vitagraph was steady work, it seemed the better deal. James Young was hired as well, first as an actor. He then turned to directing as well and became one of Vitagraph's best. Her parents followed, and they joined the other Vitagraph families, including Maurice Costello and his daughters, Talmadge sisters, and the Sidney Drew family. She probably joined Vitagraph in 1912, though some sources place her there as early as 1909.

|

|

| Young during her ingenue period at Vitagraph. This photo appears in "A Vitagraph Romance" (1912), as a poster that her father sees outside of a movie theater. |

Of the dozens of films she made at Vitagraph, relatively few survive, but many that do are quite charming and show her natural personality probably better than her later dramas. She plays some conventional leading ladies but is at her best in light comedy. A particularly good example is the unfortunately incomplete Beauty Unadorned, where she and James Young are teamed with Sidney Drew in a comedy of romantic complications. In Lord Browning and Cinderella, she strikes just the right note of lightness and subtle parody in an updating of the fairy tale. She put her stage experience to use in Goodness Gracious, a very broad and energetic parody of melodramatic conventions with Sidney Drew. She became one of Vitagraph's most popular leading ladies, placing at number seventeen in a popularity poll of stars conducted in 1913.

Vitagraph continued to produce dramatic one and two reelers into 1914 and 1915, but did try out a few features. It starred Young and the popular leading man Earle Williams in one of their earliest, My Official Wife. The film, now lost, was a huge success and launched Clara Kimball Young and Earle Williams into first place in the popularity polls. Her role was a fascinating one--a fanatical nihilist who uses her charms to worm her way into Russian high society in order to assassinate the Czar and eventually comes to a bad end when she and the nobleman she seduced are torpedoed aboard his yacht. The film was one of many in the pre-revolutionary years dealing with Russian, and remained a well-remembered favorite of Young's fans. It also brought attention to director James Young, who went on to a significant directorial career.

Louis Selznick, an ambitious producer with an ultimately fatal habit of antagonizing powerful business rivals, saw a potential goldmine in Young. He signed her 1914 and immediately starred her as Lola, a woman who is transformed from a respectable young woman into a vamp who heartlessly destroys men after her dead body is resurrected without a soul. This was another hit which cemented Clara Kimball Young's position as a top star and James Young as a sought-after director. She was now one of the chief attractions of World Film Corporation, for which Selznick had become the vice president.

Meanwhile, Selznick and Young's personal lives were becoming intertwined. Mabel Normand later recalled James Young on the set in 1915, head in hands, saying "where I made my mistake was in ever inviting that fellow to the house." Selznick's wife had to endure the humiliation of escorting Clara to public events to squelch rumors, which apparently fooled no one. James Young ceased directing her films after The Heart of Blue Ridge (1915), and in 1916 sued Selznick for alienation of affection. Clara counter sued charging cruelty, and Selznick replied that the marriage was already in trouble before his appearance. James Young finally obtained a final decree on April 8, 1919, on grounds of desertion.

It seems odd that after her success in two bad girl roles, World would cast her chiefly as hapless heroines with conventional happy endings. Some, like Camille and Trilby, have more prestigious literary roots and were allowed a tragic finale. She made further contributions to the "passionate, corrupt Russia" genre with Hearts in Exile and The Yellow Passport. But most of her films sound fairly routine and conventional. And, according to Frances Marion, she was becoming bored with her tragic heroines and increasingly resentful of Selznick's management of her private life to match the public image he had constructed as a gloomy tragedienne.

|

|

| A glamour pose of Young in one of her spectacular gowns. This gown appeared in Midchannel. Lucile-expert Randy Bigham believes this is one of Lucile's creations. |

In February 1916, Selznick was ousted from World, but he had a surprise up his sleeve. As it happened, Clara Kimball Young was under contract, not to World, but personally to Selznick. His rivals had rid themselves not only of Selznick, but also of their most popular star. Within months World was reissuing most of her films.

Selznick lost no time in forming the Clara Kimball Young Film Corporation, with himself as president, and formed Selznick Productions to distribute her films and those of some other independent producers. He wanted to make Young's films bigger and more sensational than ever. The length expanded from five to seven reels, and reviewers first began noting Young's fashionable wardrobe. But the most striking aspect was the risqué subject matter with provocative titles like The Common Law, The Foolish Virgin, The Easiest Way, and The Price She Paid. As interesting as these sound, it is sad that none survive.

After four films under Selznick's exclusive control, Young seems to have had enough. At some point, she had made the acquaintance of one Harry Garson, a Detroit exhibitor. He must have talked a good line, because in 1917 there began the first of a series of somewhat farcical and ultimately draining lawsuits and public charges and counter charges between Louis Selznick and Young. In June, 1917, she charged Selznick with defrauding her of her profits through a series of dummy corporations and by electing himself president of her company while not permitting her any voice in her affairs. Selznick denied the charges and enjoined her from appearing in anyone else's films, noting that she was now following the advice of Garson and was planning to appear in films under his direction. Shortly thereafter Young announced plans to form her own company, stating that she was to be completely in charge of her career and of all artistic and business decisions. She also noted that she would "have nothing to do with any picture which is at all likely to run foul of censor boards." Meanwhile, Selznick was suing Garson to keep Garson Productions from doing any business with Selznick Enterprises, while Garson claimed Selznick had broken his contract by his failure to deliver any more Clara Kimball Young productions! In August, the C.K.Y. Film Corporation was formed, with additional backing from Selznick archrival Adolph Zukor. At the same time, Zukor secretly bought 50 percent of Selznick's company and, while leaving him in charge, changed the name to Select Pictures Corporation. Young produced her pictures under her own company, but distributed through Select.

As with Selznick before him, Garson also had a personal relationship with Young. Back in February of 1917 they had made headlines when James Young, apparently still not reconciled to the loss of his wife, assaulted Garson with a knife as he and Clara exited the Astor Theater in New York. In early 1918, Clara and a party including her parents and "business manager" Garson moved to California. By June they were announcing plans to build a studio and gave a lot of press releases about her cross-country tour and various other plans, with Garson's name becoming more prominent in each. He also secured the services of Blanche Sweet and Marshall Neilan and started promoting himself as a producer.

The films of the C.K.Y Film Corporation sound like another interesting group of which, again, all are lost. Elaborate gowns continued to be a noted feature, but footage was cut back to five reels. While not as titillating as her Selznick films, she did continue with more adult themes, usually playing a woman who makes decisions for herself. In Magda, the first under this arrangement, Young had a particularly interesting role in this Sudermann adaptation as a woman who flees from her narrow-minded father to become a famous opera singer and refuses to marry the father of her child. These films certainly had more variety than her Selznick films, and she included a few comedies in her productions. Chief among these was Cheating Cheaters, which received outstanding reviews not so much for Young's performance as a criminal who turns out to be an undercover detective as for the clever plot and superb supporting cast.

In the January 11, 1919 issue of Moving Picture World, Young placed an ad stating "I have this day served notice upon the C.K.Y. Film Corporation of the termination of all contract relations between that company and myself, because of several flagrant violations of the terms of the agreement under which motion pictures has been produced for distribution through the Select Pictures Corporation." She added that Cheating Cheaters would be the last film to be released. The suits and charges started again, Selznick pointing out Select owned the C.K.Y. Corporation and Young had a contract until August 21, 1921. Young and Garson began production of The Better Wife with the intention of it being their first independent feature, but it ended up being released by Select in July. That same month, Equity Pictures Corporation was formed to distribute films by Young and an unnamed star. The first films to be produced would be Eyes of Youth--by Garson Productions. While advertising yet again that for the first time she would have her own company under her complete control, the production company now didn't even bear her name.

|

|

| Young and the staff of Garson Productions in Edendale, California. Clara with the teacup, Harry Garson nearby on the swing. For a view of the outside of the studio click at the corner of the 1800 block on Allesandro, click here and for a map of the Garson Studios, click here, for a history with current pictures, click here, and for a picture of Clara standing outside one of the buildings, click here. For a nice picture of Clara with Harry Garson see Starstruck in Chicago from the Chicago Tribune (you may have to scroll down to see or wait a while for it to load). There was some hyped info on Harry Garson online in The Blue Book of the Screen, but that site was closed--i've put in a link to a Wayback Machine cache, hope this works. |

To launch Garson Productions and Equity, they needed a big hit and Eyes of Youth delivered. Young's most popular film since My Official Wife and still the best known of her films today, it was probably the best she ever made. Young had a showy role as a woman asked to chose among several suitors, and envisions her futures with each one--as a downtrodden spinster schoolteacher (a role unique in her career), as a temperamental opera singer who has had to pay a high price for her success, and as a society wife smeared by her unfaithful husband and reduced to poverty and drug addiction. All this and a happy ending too proved a winning combination. Also evident were high production values, fashionable gowns, and a splendid supporting cast. Today, however, the film is best remembered as being the highest profile appearance of Rudolph Valentino before his breakthrough role in Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Lots of money seems to have been poured into advertising as well. At this time a young Gloria Swanson was impressed with Young as a woman who spoke as confidently about business as a man. She didn't find out until later that Young was putting up a brave front--Selznick was suing again, threatening exhibitors into canceling bookings for Eyes of Youth, and Equity Pictures was already in the red.

At this point, Garson's ambitions turned toward direction, and he took the helm of her next nine films. Garson proved an uninspired director with a weakness for redundant and irritating intertitles. Though he did little damage to films with strong scripts or in which Young was well cast, he was less successful with weaker material and seemed to get worse with experience. There were always budget problems as well. By his last two films reviewers were openly complaining of the bad direction.

A greater percentage of Young's films survive from this period than any other, and they show a steady spiral downward. Her next few films still were glitzy productions and some were solid stories with themes suitable to her increasingly mature appearance. But some still stressed a youth that she no longer possessed , and she was no better in saintly parts than she had ever been.

By Hush (1921) Moving Picture World was carrying a suspicious number of stories about the success of Midchannel (1920) and Young went on a big publicity tour to promote her films. Hush also included a publicity campaign that largely fizzled in New York. A more telling tidbit from Moving Picture World is that Equity, which had been listed under Miscellaneous Releases, slipped into the States Rights column, though, typically, they tried to put the best face on it. It seems likely that the distribution problems were getting worse. The lawsuits continued, and things did not go well for Young. The courts ruled that she owed Selznick $25,000 for each of the next ten pictures she made. She was sued by the Fine Arts Film Corporation of Michigan and the Harriman National Bank, which also complained that one of its agents "was beaten by "a friend of Miss Young's when he attempted to server her with papers." Moving Picture World ran increasingly desperate-sounding stories attesting to her popularity, sometimes with personal appeals by Young. Their last Equity films, What No Man Knows and The Worldly Madonna, look distinctly cheap.

In 1922, Young and Garson abandoned Equity, and the name Garson Productions appeared no more. Garson was unpopular around Hollywood for his interference in Young's career, and friends sadly regretted her naiveté. Screenwriter Lenore Coffee, who was friends with both, observed that their mutual passion was destroying both of their careers, for the hapless Garson had also thrown all his own money into the enterprise. At some point, Adolph Zuckor is said to have offered her a contract if she would guarantee non-interference from Garson, but she refused. Instead, Young and Garson joined with Sam Zierler of Commonwealth Pictures Corporation, with Samuel Zierler Photoplay Corporation as the nominal production company, to be distributed by Metro (except in New York, where Commonwealth would take over).

Garson's first and last directorial effort for Zierler/Metro was the disastrous The Hands of Nara. At this point, somebody pulled the plug on Garson. Though he continued to claim credit as producer, experienced directors such as Wallace Worseley and the up and coming King Vidor were brought in to try to salvage the star's name. Metro seems to have exercised due diligence in promoting her films. The films themselves seem to have been a mixed lot. The one surviving film, Enter Madame (1922) was well received, but appears to have been too little too late. Reviewers and exhibitors, who had earlier began to mention on her age, now began comment on her overacting. That year, Variety had remarked on how far she had fallen in the last two years, attributing it to her poor vehicles. Her last film for Metro was A Wife's Romance (1923). Though more films were announced, none were made.

In 1925, Young came back for one more silent. Garson's name was nowhere in evidence. This was en effort by the independent producer Ivan Simpson, Lying Wives, in which she played a villainous role to Madge Kennedy's heroine. Reviews were poor, and there were no more films for Young in the 1920s.

Young spent the rest of the 20s in vaudeville and other personal appearances. At some point she finally rid herself of Garson, and in 1928 quietly married Dr. Arthur Fauman.*

|

|

| Young and Freeman Wood in "Kept Husbands" (1931) |

The coming of sound boosted her career a bit, but not for long. Her first talkies was a comic featured role in RKO's Kept Husbands (1931), followed by leads in leads in Tiffany's Women Go on Forever and Monogram's Mother and Son. But she quickly dropped down to small or bit parts in low budget films and extra roles at the bigger studios. She appeared in serials and even in a Three Stooges short. One memorable bit was in Cecil B. De Mille's publicity short Hollywood Extra Girl (1935), shot while she was appearing as an extra in The Crusades. One wonders why she didn't get better roles. She seemed to be a natural for society parts, as she was still attractive and stylish in the early 30s . But it seemed that the press had already cast her as a pathetic has-been, printing story after story about her various misfortunes-her demotion to extra work, her bankruptcy, a suit against a relative for an unpaid loan, the loss of her jewelry. They even ran her pictures in a story about James Young's latest divorce. Like many silent performers, though she found work in Westerns, appearing to advantage in three Hopalong Cassidy films, as well as one film each with Gene Autry and Richard Dix. She also appeared in radio. She later told reporters: "during the depression I had half a mind to take up a tin cup and beg for alms."

She must have gotten back on her feet, since she retired from film in 1941, saying "I've been working since I was 2 years old, I think I deserve the chance to quit and just enjoy life." She did make one more film appearance, as herself in Mr. Celebrity (1942, AKA Turf Boy) with another former star, Francis X. Bushman. Her husband had died in 1937, and her father in 1938, and she continued to live in Hollywood where much of her extended family, many of whom were also in show business, had settled. In early television, lack of original programming lead to airing of silents, and Young's films, and Young herself, resurfaced. She gave interviews and made the rounds of early film conventions, and was one of the popular celebrities who celebrated the 60th anniversary of the founding of Vitagraph in 1956. That same year she was hired by the CBS as a Hollywood correspondent for Johnny Carson. Still as optimistic and cheerful as ever, she reminisced for the press, saying: "I've seen my ups and downs, and I haven't regretted a minute. I'll be working with current stars and newcomers, so I don't have to worry about getting old."

Time eventually caught up with Young. Her last place of residence was 807 North Curzon Ave, but after almost a year of ill health, she died on October 15, 1960 at the Motion Picture Home. She told old friend Frances Marion "I was worn out from the long journey, but I have found my way home." Her funeral was attended by several hundred friends, including many former stars such as Betty Blythe and Louise Dresser. Co-officiating at the rites was former Eyes of Youth co-star Gareth Hughes, by then a retired missionary. Clara Kimball Young is buried at the Grand View Memorial Park in Glendale.

What was it that killed Clara Kimball Young's career? Most sources chalk it up to Harry Garson's mismanagement, and that was certainly a factor. She could exhibit a contrary streak (relatives said that if you wanted her to do something, tell her not to do it), and this may have predisposed her to rebelling against Selznick and continuing to stick with Garson when it was clear he was harming her career. But it probably also gave her the courage to strike out on her own, becoming one of the highest profile independent stars. Part of her problem was Garson's ambition and directorial limitations, but also the founding of a new production and distribution company at a time when large companies were increasingly dominating both ends of the business was a tactical error which helped marginalize her films. The film business was also experiencing a recession in 1920. The law suits drained much needed capital. Gloria Swanson says she was blackballed by the studios to punish her for daring to go independent, but it seems that Zukor and Metro were willing to exploit any star power she might have left if Garson could be sidelined.

|

|

| An older, but still attractive Young in 1932, costumed for the film Probation. |

But even Metro couldn't rescue her once she was on her way down, so other factors were also in play. By 1920, she looked considerably older than actual age of 30, and she was growing noticeably matronly at a time when other stars were dieting down to svelte, boyish figures. The more mature parts she naturally gravitated to were also against the tide of youth-oriented films and stars coming to the fore. As other top-flight stars made bigger and bigger pictures, Young's pictures got smaller and cheaper. Another important factor was acting style. With the increased popularity of stars with a more naturalistic style, exemplified by Norma Talmadge, Young's emphatic manner looked increasingly old fashioned. Even with the backing of Metro, she couldn't adapt to the changing times. Her name recognition may have worked against her, making her better copy as a has-been than as a working actress. Like Francis X. Bushman, she was identified with the "dark ages " of movie making, films which by the early thirties were already being ridiculed, Fractured Flickers style, on movie screens across America. Young was now a symbol of antiquity.

She deserves better than that. She was a star of great historical importance, but also a talented and engaging screen personality, whose best films should be more widely seen.

Clipping Files, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Billy Rose Theatre Collection

Moving Picture World, 1916-1923.

Carr, Harry. "Untold Tales of Hollywood." Originally appearing in Smart Set, reprinted in Taylorology 43

Davis, Henry R. Jr. "Clara Kimball Young." Films in Review (Aug./Sept. 1961).

Golden, Eve. "Clara Kimball Young: Dark Madonna of Early Silents." Classic Images (June 1995): p. 22-24.

Marion, Frances. Off with their Heads. New York: Macmillan, 1972.

Slide, Anthony. The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998.

Swanson, Gloria. Swanson on Swanson. New York: Random House, 1980.

Thomas, Bob. Selznick. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1970.

And thanks to Barbara Ulibarri for information on Young's later years.

* Thanks to Eric Fauman for sharing his geneological research. Dr. Arthur S. Fauman was a Toronto dentist, and was apparently born in South America as Abraham Saul Fauman. He was living with Clara at 1408 North Havenhurst Drive, West Hollywood (the same building as 1414 Havenhurtst), and is recorded as Dr. Abe Fauman at that time. He and Clara didn't announce their marriage until a 1934 auto accident brought it into the open. He and Clara were living at the Waring Ave. house when he died in 1937 at the age of 45. He is buried at Grand View Memorial Park next to Edward Kimball, who died the next year.

©2001, by Greta de Groat.

Back to Clara Kimball Young HomeLast revised December 27, 2015